BUFFALO, N.Y. — The year was 1935 and this industrial, Western New York city had evolved into a hub with a burgeoning music scene. Scores of Black families relocated from the South for jobs at the steel mills.

Black musicians, even visiting headliners the likes of singer/bandleader Cab Calloway, weren’t allowed to drink at the white clubs and had to enter and leave through back doors. But after working their shows, they needed a place to loosen their collars and unwind. After floating around for years, they made a permanent home in 1935 at 145 Broadway St. and called it The Colored Musicians Club.

Now, the club in downtown Buffalo is celebrating its 90th anniversary, fresh from a gala event to commemorate the milestone. And the club’s leaders are sharing stories about its beginnings.

“One of the old timers was telling us a story of a band leader being so impressed with the guys here one night, he was on the phone calling other directors back home saying, ‘Man, you won’t believe these cats in Buffalo! They are something else!’ ” George Scott, board president, told Black News & Views in a sit-down interview.

Today, the Colored Musician’s Club & Jazz Museum is busy with plans for expansion using historical preservation grants from state, county, and city sources, an endowment from the Ralph C. Wilson Jr. Foundation (original owner of the Buffalo Bills NFL franchise), and other private donations. The club has acquired the building two doors over, and plans for it to be used as a music school are in the works.

The genesis of the club’s history actually goes back more than its 90 years, to 1917.

America was dancing to its first commercially successful jazz recording, “Livery Stable Blues,” recorded by the all-white Original Dixieland Jazz Band, who claimed to have invented jazz themselves. The recording sold over a million copies.

At the same time, the Great Migration from southern states was underway, bringing droves of talented Black musicians to the industrialized North.

“Back then, for a good paying musician’s job in a nightclub in Buffalo you had to be a member of the Local 43 [union], which of course excluded Blacks,” Scott explained, referring to the all-white American Music Federation.

Buoyed by unity

There was the option of forming a Black subsidiary to the local union, which usually meant less desirable jobs, paltry pay, and no representation.

Undeterred, Buffalo’s Black musicians chose that year to form their own union chapter, Local 533, making them only the eighth Black labor union in the country and the first Black union in Buffalo.

“Buffalo’s white population then was somewhere around 400,000,” board member and historian Craig Steger said in an interview with Black News & Views. “You want to guess the Black population? Two thousand. That’s one half of 1%. So this was a big economic gamble at that time,” Steger said.

First, union business operated downstairs. When touring Black musicians came to town, they had to register with 533 in order to work. Once upstairs, they could get pigs feet, a plate of beans, and a beer for 25 cents, share tips about upcoming gigs, and break out into impromptu jam sessions with the locals trying to best one another any night until all hours of the dawn.

It was at these jam sessions where Buffalo’s boys shined, garnering a far reaching reputation as some of the top musicians anywhere.

“Now when the big touring bands went out on the road,” Scott explained, “they usually only brought five or six musicians with them, and picked up the rest from the union wherever they were playing.”

Buffalo’s union only accepted musicians who could sight read music, respond on the fly to calls for key changes, and, especially, demonstrate they could play in an ensemble without upstaging the lead.

It wasn’t uncommon for a local player to get picked up from one of these jam sessions to tour with a band. Buffalo violinist LeRoy “Stuff” Smith, picked up from such a session, traveled with both Dizzy Gillespie and Jelly Roll Morton, a.k.a. Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe. Famed orchestra leader Jimmie Lunceford sharpened his chops at Buffalo’s Arcadia Ballroom before replacing Cab Calloway at Harlem’s legendary Cotton Club in 1934. Jazz pianist and second wife of Louis Armstrong, Lil Hardin Armstrong, was devoted to the club. According to Scott, she left provisions for three years of dues to be paid in her name beyond her passing. Buffalo pianist Wade Leggee was recruited by icons Gillespie and Sonny Rollins for a brief but spectacular few years.

Anyone could show up on any given night. Buffalo pianist Boyd Lee Dunlop described a special encounter when he was only 16.

“It was 1953,” the club’s website quotes Dunlop as saying. “I got to the club at 4:30. … After our jam I stayed around and Billie Holiday showed up and wanted to sing. I didn’t know who it was at first but as soon as she started to sing I was like,’Oh my, I’m playing for Ms. Holiday.’ As soon as we finished, I called my mother from a pay phone inside.”

Scott shared photos that include none other than Dizzy Gillespie himself at the club’s piano. A young man whose fingers are on the door frame is be-bop forerunner John Coltrane. Behind him is an eager Miles Davis waiting for his turn. Holding the trumpet is Buffalo musician Elvin Shepherd. “Shep” was offered a job in Gillespie’s orchestra, but there was only room for one great trumpet player, and the band already had one of course in Gillespie. He bought the saxophone from the musician on the right, Wilbur Trammell, who traded in his musical aspirations for law school and went on to become Buffalo’s first Black City Court chief judge.

All in a typical Tuesday night at the club, and local newbies could go home with a story of having sat next to such greats trying their best to keep up. The traveling fellahs came home to 145 Broadway St. with wild stories from the road that could only be shared amongst the boys with a knowing wink over bourbon and cigars.

“You have to remember,” Scott explained, “most of our history, Black folks’ history, is oral. We’re not heavy on the written word like white people are. Our history has always been about young people being around the older folks hearing them telling the stories, and passing on the knowledge that way.”

David Jonathan Hulett embodies the spirit of carrying that knowledge into the future. He is the drummer and frontman of David Jonathan and the Inner City Bedlam, a pioneering, eclectic, jazz-soul-’70s-storytelling-fusion ensemble that isn’t neatly put into any one pigeon hole. Jonathan was first brought to the club in the 1980’s by his music teacher at Buffalo’s public performing arts high school. Word of the Sunday jam sessions brought players from as far as Toronto and neighboring Pennsylvania to share in the experience, and the dare to be better that being around skilled players can bring.

“On any given Sunday we used to see [funk bass player] Oscar Alstin, all them brothers from Rick James’ Stone City Band, Earl Roberson [saxophonist for The Gap Band, Charlie Wilson] they used to just be in there with us,” Hulett told BNV.

Through this exposure, Hulett could really see music as a professional path forward.

That’s what gives club its sacramental purpose and meaning. Its walls are the repository of 90 years of Black stories, music, and knowledge. Like in the spectacular juke joint scene in writer/producer/director Ryan Coogler’s movie “Sinners;” when the musicians convene in this space, a veil is pierced making past, present and future all seemingly accessible to draw from.

A model of solvency

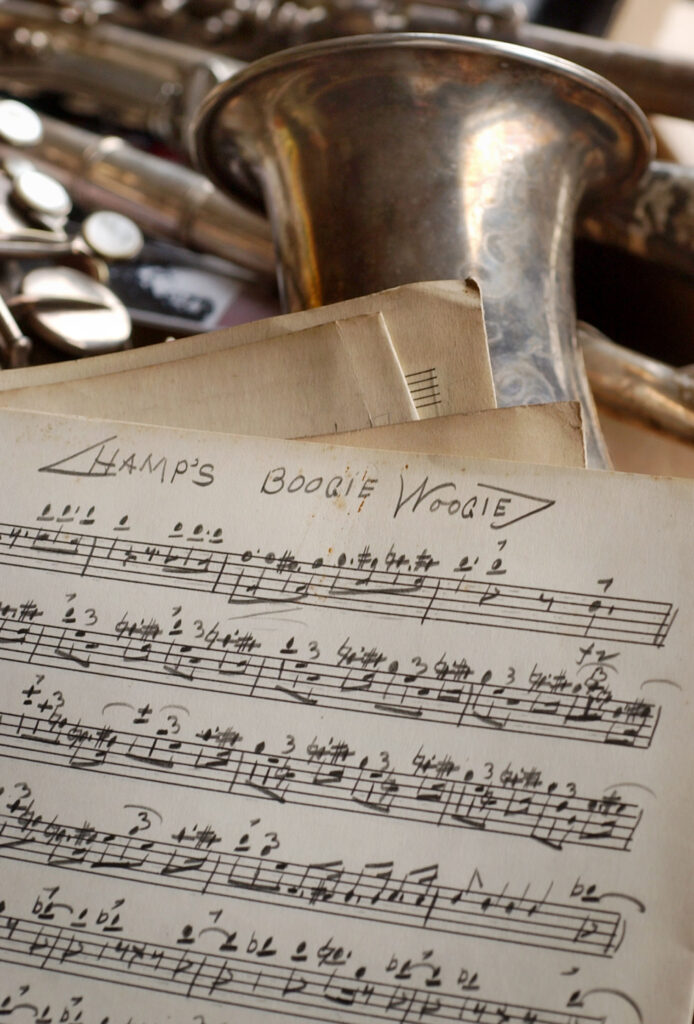

Nationally, Buffalo’s union was a model of economic soundness early on. Raymond Ellis Jackson played clarinet and saxophone and was a founding member of Local 533.

With only two years of high school, Steger explained, “Jackson managed their books so solidly they were able to offer home loans to their members, auto loans, life insurance, and this is in the thirties and forties when banks don’t want to do business with Black people, right? Think about what that provides for a whole community.

“So when the national union saw what Buffalo was doing, it hired Jackson in 1936 to travel the country showing all its local Black affiliate clubs how to get their act together too.”

Pursuant to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the American Federation of Musicians insisted that all local clubs integrate so in 1969, Local 533 and Local 42 combined to form Local 92. The merger of their finances brought the latter’s books up to solvency, and the former’s coffers worse for wear. Thanks to the foresight of Raymond Jackson all those years ago though, the social club itself was established as a separate entity from the union so the club—and the building—survived the merger and continued on as a meeting and learning space for Black musicians. In fact, the Broadway Street building remains this country’s only musicians club of its kind still standing. The building was made part of the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.

Part of Buffalo’s Black history

Along with the Nash House Museum, the Michigan Street Baptist Church, and the headquarters for radio station WUFO, it is one of several nearby buildings in what is designated Buffalo’s Michigan Street African American Heritage Corridor.

The Michigan Street Baptist Church, completed in 1849, was central to Buffalo Black life. It was a last stop on the Underground Railroad for many escaping slavery. The church had a national celebrity member in Mary Burnett Talbert, a founding member with scholar W.E.B. DuBois of the Niagara Movement, the precursor to the N.A.A.C.P.

The Rev. J. Edward Nash Sr. was the church’s pastor until 1953. In the family’s home, items were found after his death preserved in near pristine pre-WWII condition. Irreplaceable papers, books, notes of visits from the likes of Booker T. Washington, furniture, even a victrola and other items are on display for the public.

AM radio station WUFO was the first in Buffalo to have all-Black programming, a revelation in 1961. Imhotep Gary Byrd got his start on air here when he was just 15. He went on to a successful career as a New York City talk radio host, and won an award in 1984 for a British television special he did with Gil Scott Heron and James Brown.

Today, members past and present, and well wishers, are riding high from the wave of the club’s black-tie 90th Anniversary Gala that took place on Sunday, Sept. 21, at $150 a head. There was fancy food, speeches and proclamations from politicians, the usual fare.

However, there are 12 members of the original Local 533 that was disbanded in 1969 and the night was special, in honor of them. There were 12 opportunities to hear the stories one more time from guys who can actually say “nah, man, you got it all wrong! I was at the club that night, that ain’t what happened! You see what really went down was…”