Some call it the unfinished march.

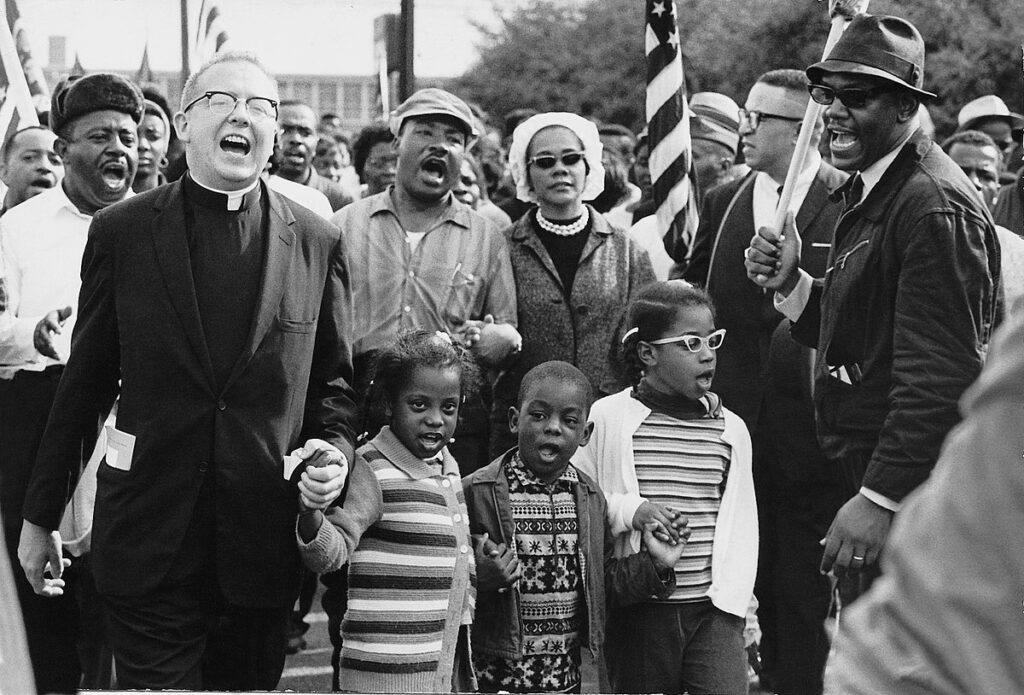

Sixty years after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) was passed, the battle for the ballot continues. With a stroke of the pen, and after decades of struggle, the bill so many had fought so long for, finally became law. It was a legislative earthquake that sought to end the political violence of the Jim Crow era and grant Black Americans the opportunity to vote, ensuring their fundamental right to determine the course of the country.yould probably bring an end to voting discrimination, which the law itself did. But as various states pushed back, civil rights organizations sort of dropped the ball after the law was passed,” said Raoul Cunningham, former president of the Louisville chapter of the NAACP. The law seemed so strongly embedded that many groups moved on to focus on other forms of discrimination even as the VRA’s opponents laid the groundwork for its eventual weakening.

But the legacy of this triumph is being challenged, serving as a sobering reminder that the road to full voting equality isn’t complete.

Advocates felt “that a major accomplishment had been made. Discrimination and segregation in public accommodations had ended. We had also ended the poll tax and various tactics of denying the right to vote. But we dropped that ball. We became secure, complacent. Complacent is a better word.”

According to Cunningham, the VRA gave Blacks hope because it stood as a pledge that the rights of Blacks would be upheld and that their desires would be heard.

“We never thought that the Supreme Court would gut the Voter’s Right Act,” Cunningham said. “If you look at what we thought in [19]64-[19]65, and to what happened in 2013 and 2022, we never thought the Supreme Court, which we have always relied on as a friend, would do this.”

The VRA was designed to combat racial discrimination in voting, particularly in the South, where Blacks had been systematically disenfranchised.

The road to voting rights was paved in blood

This landmark legislation was the result of years of activism, sacrifice and persistent demands for equal rights.

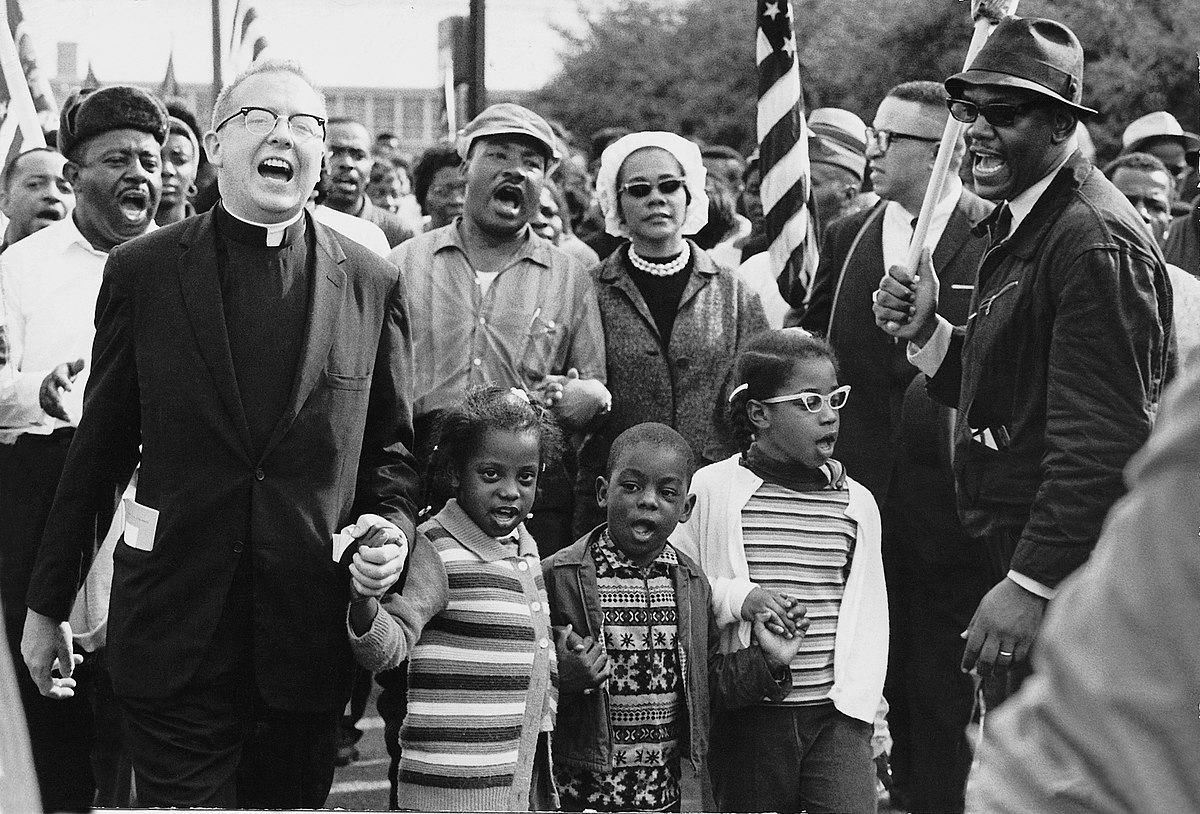

The VRA emerged from a tumultuous period in the civil rights movement. Activists, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis and many others, had fought against segregation, voter suppression and violent resistance to change. The events of “Bloody Sunday,” where peaceful marchers were attacked on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Al., galvanized public opinion and led to the passage of the Act.

The VRA targeted laws and regulations that had been used to prevent Blacks from voting, including literacy tests and poll taxes. It gave the federal government the power to oversee voter registration and elections in areas with a history of voter suppression. The Act also included provisions for federal examiners to register voters directly and ensure that changes to voting laws in certain jurisdictions could not be implemented without federal approval.

This legislation had a profound impact on American democracy. It significantly increased voter registration and participation among Blacks and other marginalized groups even as the law was almost immediately challenged. Just four years after the VRA was passed, the Supreme Court, ruled 7-2 in favor of the plaintiffs in Allen v. State Bd. of Elections and held that all changes to election rules in covered jurisdictions, no matter how small, were covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

The reason this decision was so important was that it made it clear that Section 5 was intended to preclude any new voting laws or procedures from either limiting or denying the right to vote on the basis of race. The VRA is widely credited with reshaping the political landscape of the United States, leading to greater representation and advancing civil rights. Research from Oxford University shows that racial representation in local governments was significantly impacted by the Voting Rights Act, and that this greater participation resulted in noticeable improvements to Black communities’ quality of life.

According to data from the NAACP and the U.S. Census, between 1962 and 1980, the number of Black elected officials in local governments throughout the South increased significantly. Research indicates that in 1962 there were fewer than 1,500 Blacks appointed to local government positions. By 1980, there were 6,440 Black elected officials. Spending on public infrastructure throughout Black neighborhoods increased, too. In 1962, public infrastructure spending in Black neighborhoods throughout the South averaged $1,000 per capita. By 1980, public infrastructure spending increased to $2,000 per capita. (*These figures are not adjusted for inflation.)

“I think the two guiding stars are Thornburg v. Gingles from 1986 and then Allen v. Milligan from 2023,” said Bryan Sells, a former special litigation counsel in the voting section of the Civil Rights Division at the United States Department of Justice and currently in private practice in Atlanta, focusing on election law, voting rights and redistricting. “Both of which were forceful reaffirmations of Congress’ power to pass the Voting Rights Act to remedy generations worth of voting discrimination in America.”

“One of the things that you often hear in the media these days, some commentators say that racial discrimination in voting is a thing of the past. It’s over. It has been completely fixed and perhaps replaced with political discrimination in voting,” Sells said.

“Which may or may not be illegal, but people say it’s just natural that Black voters would vote for Democrats and white voters would vote for Republicans. And I want to say, as forcefully as I can, that there’s nothing natural about that.”

“The VRA was needed in 1965 because of systematic, widespread voting discrimination against Black Americans in some parts of the country,” said Hans von Spakovsky, a lawyer and former member of the Federal Election Commission nominated by George W. Bush who is a senior legal fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation. “Today, such discrimination is extremely rare, and when it does happen, Section 2 of the VRA is a powerful tool to remedy it.”

Sells contends that restoring the power that people once had at the polls is necessary, but it is difficult to advocate for without any legislative support.

“I’m not privy to their internal conversations, obviously, but what you can tell as an external observer is that they [the Trump administration] are retreating from enforcing the Voting Rights Act as Congress intended,” Sells said. With regard to the VRA, the Trump administration’s activities raise concerns about the possible harm to voter access and the implementation of safeguards against racial discrimination in elections. Such as reduced enforcement, dismissed cases, executive orders, and a new found focus on voter fraud.

“They have dismissed some or almost all of their existing litigation against or litigation to enforce the Voting Rights Act and frankly they don’t seem to be enforcing other provisions, statutory provisions that Congress has charged this department with enforcing, such as the Help America Vote Act, the National Voter Registration Act, the Move Act and so on. They simply seem to be doing little to nothing at the present time.”

Challenges and changes: The gutting of Sections 4 and 5

Despite its successes, the VRA has faced mounting challenges in recent years. One of the most significant setbacks came in 2013, when the Supreme Court struck down several provisions of the VRA in its Shelby County v. Holder ruling.

In particular, the court determined that Section 4(b) of the VRA, which defined states with a history of racial discrimination, was unconstitutional due to the law’s failure to take into account current conditions. This decision effectively gutted Sections 4 and 5 of the act, which had provided the framework for preclearance, an approval from the Justice Department or federal courts for changes to voting laws, processes and districts.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg contended in her dissent in the case that regional protections under the VRA were still required. She also maintained that bills like the VRA are to be supported by Congress. She also highlighted that the decision to undercut the VRA and the continued consequences of racial voter suppression is a threat to democracy. The court also enabled some states to implement restrictive voting rules without having to worry about legal ramifications.

“Legislative efforts to revamp the preclearance coverage formula have been percolating since the immediate aftermath of the Shelby County decision in 2013,” said John Powers, a professor at American University Washington College of Law and former counsel to the assistant attorney general for the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

“For over a decade, various legislators in Congress have proposed the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. The John Lewis act includes a revamped coverage formula based on updated criteria such as evidence of recent voting rights violations, which would answer the Supreme Court’s call to create a coverage formula that is based on current conditions. The old coverage formula relied on data and criteria dating back to the 1960s.”

According to von Spakovsky, the Supreme Court addressed Section 5 appropriately.

“Section 5 was correctly and properly dealt with by the court,” he said. “Section 5 was intended as a temporary provision that only applied to a small number of states where the worst discrimination was occurring. The very same coverage formula to determine what states were covered was based on 40-year-old data, and Congress never removed it to update the formula based on current registration and turnout data…. There was no justifiable reason for them to remain subject to special coverage.”

Joshua A. Douglas, attorney, author and professor at the Rosenberg School of Law at the University of Kentucky, shared his insights on the legal aspects of voting rights.

“Support for the Voting Rights Act used to be bipartisan,” Powers noted. “The 2006 reauthorization of Section 5 was passed by an overwhelming margin — for example, the Senate voted unanimously (98-0) to reauthorize the act. A return to the bipartisan consensus that protecting minority voting rights is an important goal would be an important step.”

Douglas believes the Supreme Court’s actions were questionable, at best.

“On Section 2, which applies nationwide and prohibits voting rules that have a discriminatory effect, the court in the 2021 Brnovich ruling created five ‘guideposts’ for plaintiffs to satisfy to bring a successful claim that make it very difficult for plaintiffs to win. These ‘guideposts’ are nowhere in the statute… the court basically made up the law. And each guidepost makes it harder for plaintiffs.”

Powers feels that both parts of the VRA have been twisted by the Supreme Court to suit its interests, allowing a voter to be turned away from the polls virtually instantly with no repercussions for the election board.

Past is prologue

Historically, the U.S. DOJ has been the primary enforcement agency for Section 203 of the VRA, which offers safeguards for non-English speakers in counties with significant populations of linguistic minority voters. In recent years, the statute’s enforcement has decreased. The VRA’s Section 2 is still relevant in “vote dilution” instances, involving challenges to at-large voting systems and redistricting plans.

The core issue of these cases, according to Douglas, is extreme deference to the states regarding the manner in which they hold their elections.

“The court should more robustly protect voters, not states, in the election process. Congress could theoretically enact an update to the VRA — which would also be a good idea — but of course that would be subject to Supreme Court overview. We also need stronger constitutional protection for the right to vote,” Douglas said

The Supreme Court decision removed a critical tool for combating voter suppression and allowed states and localities to implement changes to voting laws without federal approval. Since the Shelby County decision, there has been a notable increase in the enactment of restrictive voting laws, particularly in states with histories of discrimination according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

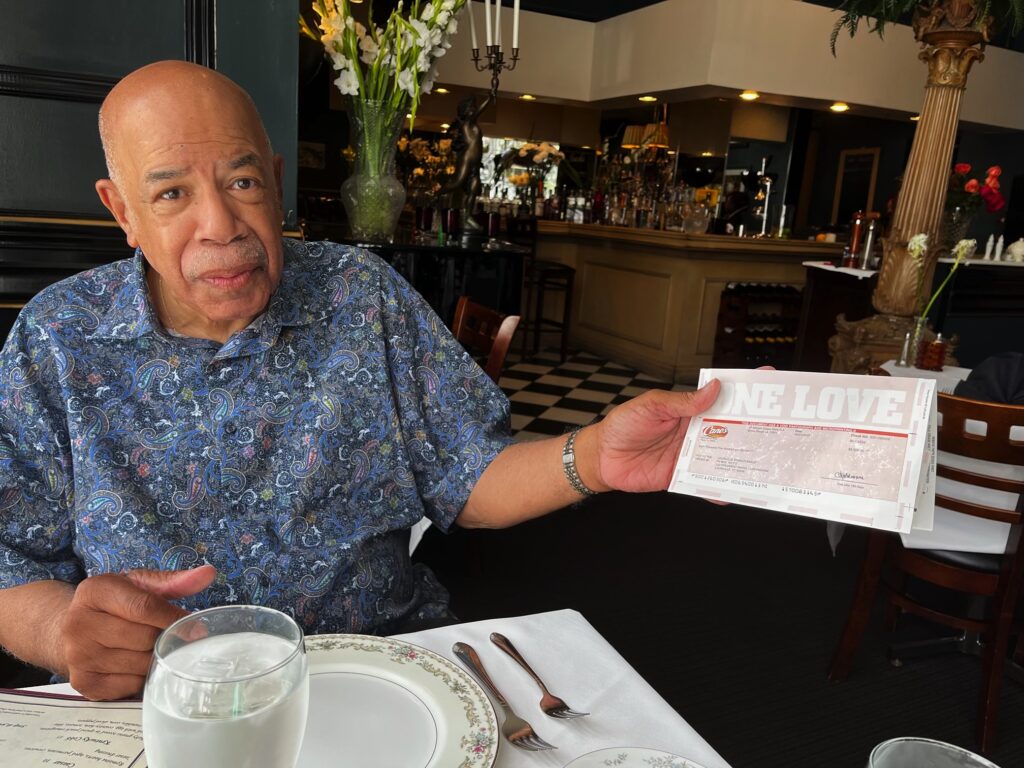

Dr. Dewey Clayton, a political science professor at the University of Louisville and author of “The Presidential Campaign of Barack Obama,” emphasized the importance of continued advocacy.

“The [voting turnout] gap between Blacks and whites essentially was eliminated, but once Shelby County came into place in 2013, then that gap began to widen,” Clayton said. “It widened in the election in 2016, (Hillary Clinton vs. Donald Trump) and it widened even further in the election in 2020.”

After the civil rights movement, the Black and white American voter turnout disparity narrowed. Data provided by the Brennan Center for Justice revealed that this tendency had been reversing for more than 10 years. A crucial indicator of equality in participation is the racial turnout gap between white and non-white voters. This trend has been steadily increasing since 2012, and it is expanding at the fastest rate in regions of the nation that were formerly protected by Section 5 of the VRA.

According to Clayton, a multiracial democracy is the reason why Obama was elected president 17 years ago. However, he also noted that the Tea Party movement gained momentum in the years following Obama’s historic presidential victory. Clayton believes that the party predicated on the fundamentals of conservative Christians to eagerly “turn the clock back” and undermine multiracial democracy.

“I think it was 1994 … once the Republicans began to have a majority in Congress, they began to wield their power,” Clayton said. “The president began to nominate Supreme Court justices that were much more conservative than they had [ever] been. And as you well know, now we have a 6-3 conservative majority, obviously in court, they have ruled on several cases lately.”

But despite the VRA being a landmark law, Clayton cautioned that its legacy is in jeopardy. By enhancing legal safeguards against discriminatory voting practices, the John Lewis Act — named after the late congressman and civil rights activist — would update and revive the VRA.

First, by establishing a new framework to identify whether areas with a history of voting discrimination are subject to preclearance, the bill would reinstate what the Supreme Court had invalidated in Shelby County. Additionally, it would impose a preclearance requirement on other repeated discriminatory policies, such as voter ID. Furthermore, the bill would reinstate Section 2 of the VRA in response to the Brnovich ruling, guaranteeing that voters have the right to contest voting discrimination in court.

Von Spakovsky argues that since everything is fine, nothing needs to be changed.

“There is no reason for a new Section 5 as proven by record registration and turnout rates, and Section 2 remains a permanent, nationwide tool that can be used in the rare cases where discrimination occurs,” he said.

Pamela S. Karlan was the U.S. deputy assistant attorney general for Voting Rights in the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division and is currently a professor at Stanford Law School.

“There’s absolutely no chance under current law that we’re going to see a revamped Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act,” Karlan said. “The important thing is that the right to vote is absolutely critical because it’s what preserves all of our other rights. The idea that we don’t have a national commitment to ensuring that every citizen who’s eligible to vote can register, cast a ballot and have that ballot counted is a real problem.”

This article is part of a collaboration with the Associated Press, Black News & Views, and the New York Amsterdam News. The work is part of the AP Inclusive Journalism Initiative supported by the Sony Foundation.