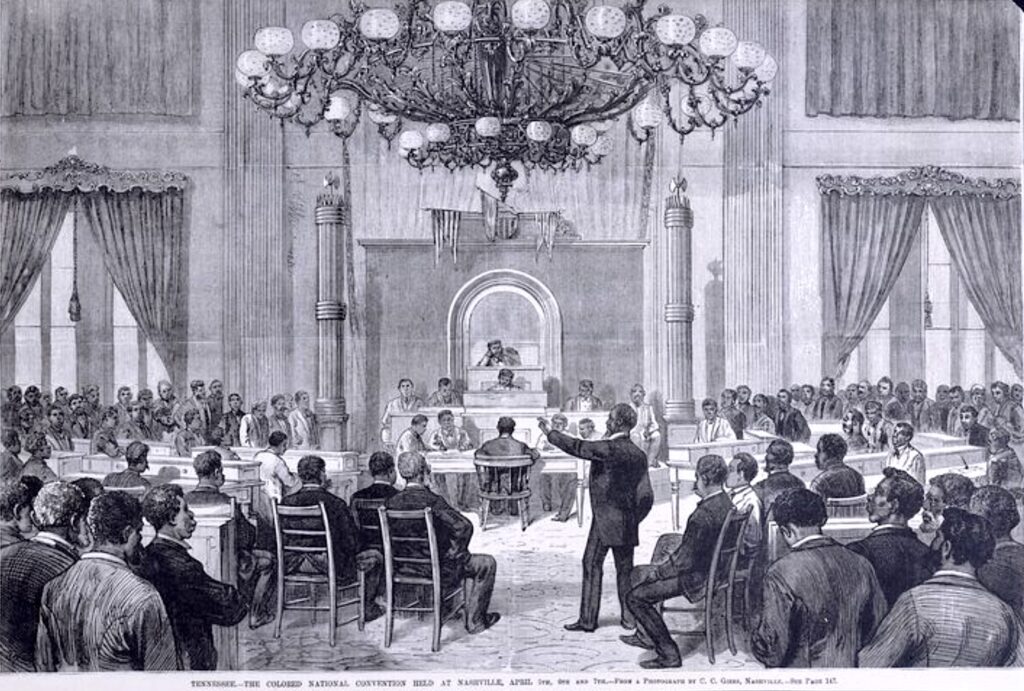

Oct. 4-7, 1864:

In Syracuse, New York, the National Convention of Colored Men – comprised mainly of delegates from the North but also some from Virginia (5), North Carolina (2), Louisiana (2), Mississippi (1), and Florida (1) – issue an eloquent appeal for an end to slavery at the end of the Civil War and the right to vote for Black men. After laying out their case, the delegates ask the American people: “Are we good enough to use bullets, and not good enough to use ballots?”

Dec. 6, 1865:

With Georgia’s vote to ratify the 13th Amendment, the required minimum of 27 out of the 36 states give their approval, thus legally abolishing slavery and involuntary servitude “except as a punishment for crime.” The amendment is passed by the U.S. Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the U.S. House on Jan. 31, 1865. President Lincoln signs it on Feb. 1, 1865, and then sends it to the states for their approval. Twenty-one states have ratified the amendment by the time Lincoln is assassinated on April 14, 1865.

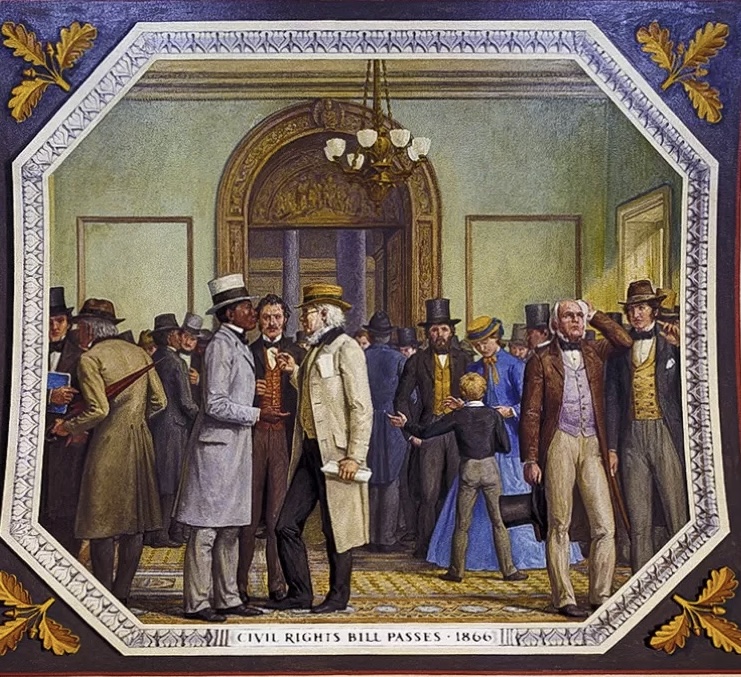

April 9, 1866:

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 declares that all people born in the United States are U.S. citizens and have certain inalienable rights, including the right to make contracts, to own property, to sue in court, and to enjoy the full protection of federal law.

March 2, 1867: Congress passes the first of four Reconstruction Acts, setting the terms by which former Confederate states would be readmitted to the Union. Among the requirements are that new state constitutions that enfranchised freedmen ratify the 14th Amendment.

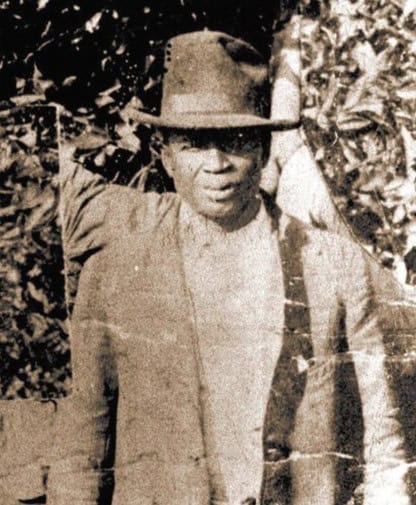

July 8, 1867:

Isaac “Ike” Aikens, an enslaved man in 1853 described in estate records of his former owner as “a fellow of 47 years old” and valued at $600, registers to vote in Jasper County, Georgia. He is one of about 93,000 Black men who register in that state (and is the great-great-great grandfather of E.R. Shipp, the author/researcher of this timeline).

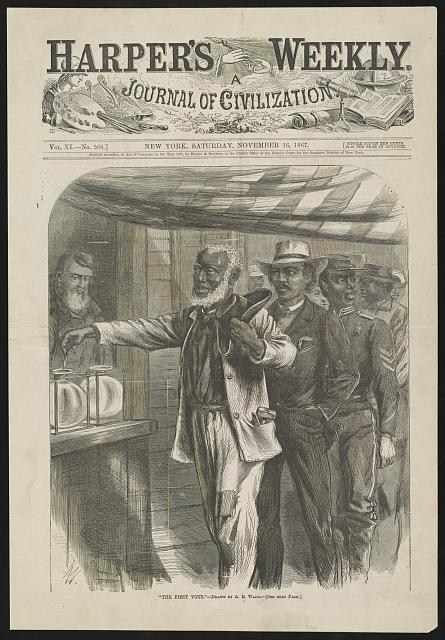

Oct. 22, 1867:

More than 90,000 Black men out of the 105,832 who registered to vote in Virginia go to the polls to elect delegates to the federally-mandated state convention that would write a new constitution in the election overseen by United States military officers. Of the 105 men elected to the convention, 24 are Black.

July 9, 1868:

Ratification of the 14th Amendment guarantees citizenship, equal protection under the law, and due process to millions of formerly enslaved people who were previously treated as chattel, livestock, or furniture. Within months, Black men begin to vote.

Sept. 28, 1868:

Acts of violence and intimidation ripple through the old Confederacy, with massacres claiming hundreds of lives, none deadlier than what began in Opelousas, Louisiana, and lasted for days. An estimated 150-300 Black people are killed, others are chased from their homes, and the Republican Party is decimated.

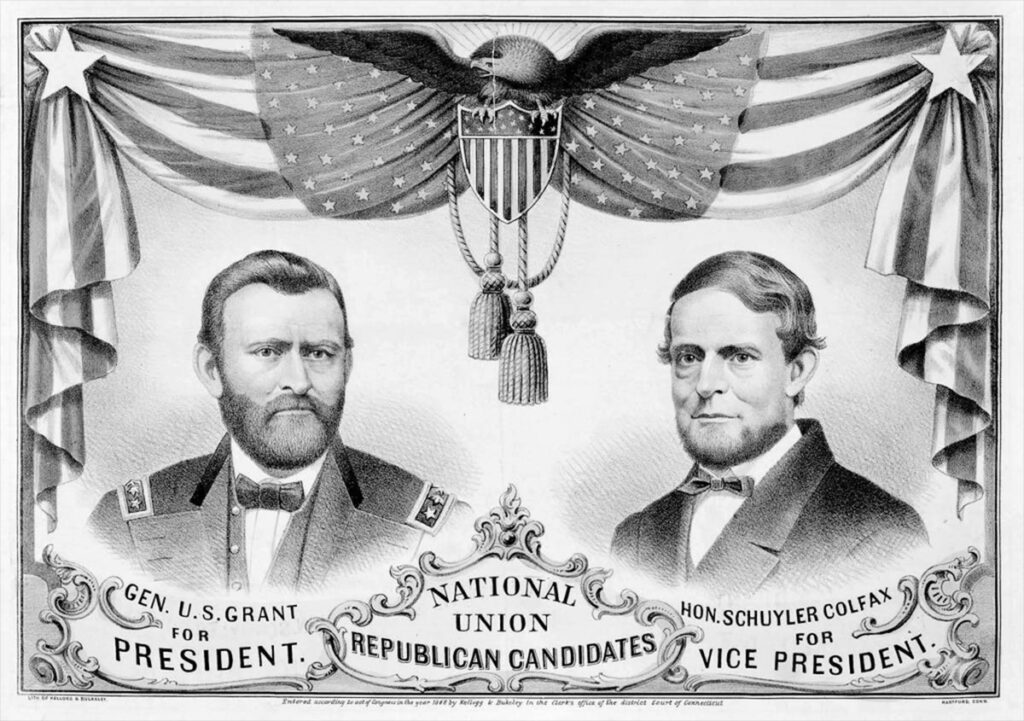

Nov. 3, 1868:

The 700,000 Black men who cast ballots propel Ulysses S. Grant to victory in the first presidential election after the Civil War. In the South, Black people are concentrated in the Republican strongholds. Grant defeats pro-South Democratic candidate Horatio Seymour by 306,000 votes.

May 31, 1870:

Congress enacts the first of three Enforcement Acts aimed primarily at criminalizing the Ku Klux Klan’s terror campaign to interfere with the right of freedmen to vote. It establishes penalties, gives the president the power to send troops to protect Black voters, and gives federal courts the power to enforce the act.

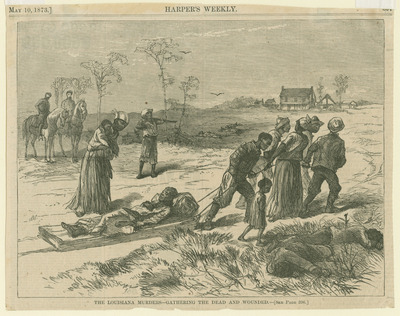

April 13, 1873:

On Easter Sunday, a mob of white supremacists from the Democratic Party storm a courthouse in Colfax, Louisiana, where Black Republicans are holed up trying to protect elected officials. Outnumbered and outpowered by the white attackers’ cannon, the Black people surrender. Many are executed on the spot. Estimates of total Black deaths range from about 60 to about 150. The federal prosecutor evokes the Enforcement Acts to indict 98 men. Only nine go to trial and three are convicted. The Supreme Court later throws out the convictions.

1873-1877:

Shelton Shipp of Rockdale County, Georgia, is among thousands of freedmen in Georgia who appear in the property registers that keep track of their employment and assess their poll taxes. Those not employed are at risk of being convicted of vagrancy and subjected to “involuntary servitude” permitted under the 13th Amendment.

March 27, 1876:

The U. S. Supreme Court guts the Enforcement Acts in U.S. v. Cruickshank, a case that grew from prosecutions of three men for their roles in the Colfax Massacre of 1873. The Court rules that the federal statutes apply to state actions, not those of individuals. As the scholar Eric Foner wrote in reviewing two books on the matter, the case “hammered the final nail into the coffin of federal efforts to protect the basic rights of black citizens in the South.” It leaves Black Americans vulnerable to voter suppression and racial violence during and after Reconstruction.

March 2, 1877:

The “Great Betrayal” begins with the announcement that Rutherford B. Hayes has been certified as winner of the 1876 presidential election. With election results in dispute, Republicans strike a deal with Democrats so that Hayes, their candidate, can be declared the winner. In exchange, Republicans agree to end Reconstruction and remove occupying troops from former Confederate states, White supremacists calling themselves “Redeemers” now have the green light to thwart voting rights and any other civil rights granted to freedmen as they take full control of their states.

Dec. 5, 1877:

Georgia’s new post-Reconstruction constitution includes stringent residency requirements and a cumulative poll tax. Prospective voters aged 21 to 60 are now required to pay a sum of money for every year from the time they turn 21 or from the time the law took effect. Later amendments add a literacy test and exempt anyone from paying the poll tax if their father or grandfather voted before slavery ended.

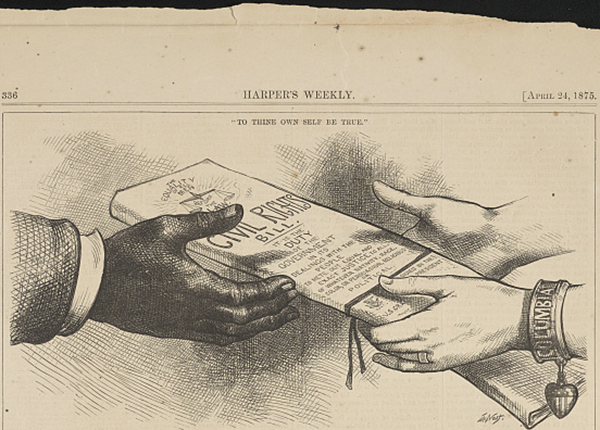

Oct. 15, 1883:

The U.S. Supreme Court strikes down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which prohibits racial discrimination in public accommodations that, 81 years after the 1883 court ruling, will become the hallmark of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Supreme Court holds that Congress can only regulate state conduct, not private acts of racial discrimination. This further guts federal civil rights protections for Black people.

Nov. 1, 1890:

Mississippi leads the way in disenfranchising Black voters with adoption of its new state constitution. Any prospective voter has to “be able to read any section of the Constitution of this state; or he shall be able to understand the same when read to him,or give a reasonable interpretation thereof.” They also have to pay any outstanding taxes, including a poll tax, before they can vote and prove long-term residency, something itinerant Black farm laborers cannot do. Other Southern states adopt the Mississippi Plan, which is upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court on Apr. 25, 1898, in Williams v. Mississippi

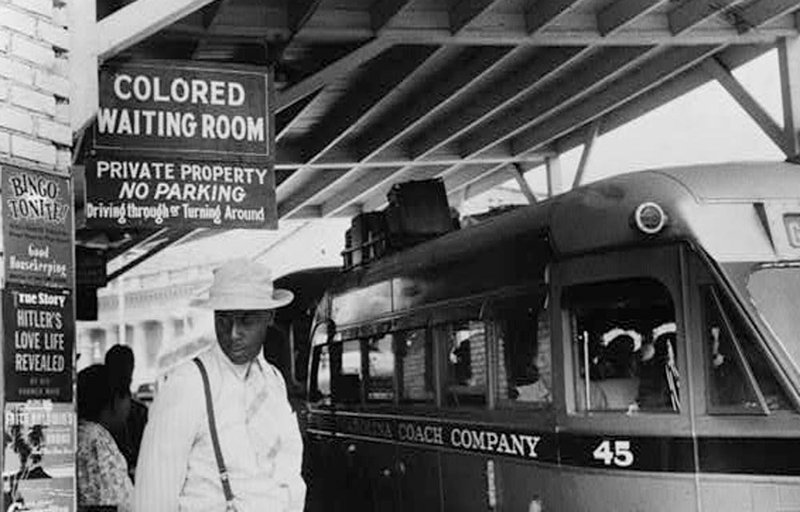

May 18, 1896:

In Plessy v. Ferguson, the U.S. Supreme Court upholds the constitutionality of racial segregation laws, giving birth to the phrase “separate but equal” that would be the law of the land for the next 58 years. The ruling further empowers white supremacists to undermine the civil rights of Black people that the U.S. Constitution and a number of federal statutes have promised since 1865.

Mar. 23, 1900:

South Carolina’s Sen. Benjamin Tillman pretty much sums up the aims and attitudes of the Old Confederacy as the 19th century rolled into the 20th. “We did not disfranchise [sic] the negroes until 1895. Then we had a constitutional convention convened which took the matter up calmly, deliberately, and avowedly with the purpose of disfranchising [sic] as many of them as we could under the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments,” he declared from the floor of the Senate. “We adopted the educational qualification as the only means left to us, and the negro is as contented and as prosperous and as well protected in South Carolina to- day [sic] as in any State of the Union south of the Potomac. He is not meddling with politics, for he found that the more he meddled with them the worse off he got….”

1900-1910:

A number of states – including North Carolina (1900), Alabama (1901), Maryland (1904), Georgia (1908) and Oklahoma (1910) – adopt laws that exempt white men from literacy tests and other requirements if they were eligible to vote by a certain date or if they descended from such persons. The date – often Jan. 1, 1867 – comes before the March 1867 Reconstruction Act requiring Southern states to enfranchise Black men, and before the 15th Amendment, adopted in 1870, saying Black men could not be denied the right to vote.

February 12, 1909:

An interracial but predominantly white group of people committed to social justice establish the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth.

March 3, 1913:

On the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, one of the nation’s most racist presidents, thousands of women converge on the nation’s capital for the first national women’s suffrage march. Racial tension between white women and Black women is undeniable. Some of the most prominent Black women activists – including Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell – first are told that Black women are unwelcome and then told that they can bring up the rear of the parade. Wells is having none of that and dashes up to join the white women marching under the banner of her adopted home state, Illinois.

June 21, 1915:

In Guinn v. U.S., a case initiated by the NAACP, the Supreme Court strikes down Oklahoma and Maryland grandfather clauses that are “repugnant to the Fifteenth Amendment and therefore null and void.” But the ruling has little effect. Like the arcade game Whac-A-Mole, legislatures came up with different obstacles to Black enfranchisement.

Aug. 26, 1920:

The 19th Amendment becomes law, granting women the right to vote — well, mainly white women. This has been a particularly arduous fight for Black women, whose rights have taken a back seat to that of Black men and who had to battle white women to be included in the larger suffrage movement. From at least the Colored National Convention of 1843 in Buffalo, New York, through the founding of women’s clubs and college sororities, and of major civil rights groups like the NAACP, Black women have been at the forefront in advocating voting rights. They realize, however, that the 19th Amendment will mean little in Southern states that use every trick in the book to deprive Black people of access to the ballot.

Nov. 2, 1920:

In Ocoee, Florida, near Orlando, dozens of Black men and women are massacred and hundreds flee. The violence begins with the lynching of Julius “July” Perry, a farmer and labor broker who, with Moses Norman, was registering Black people to vote. Norman, a landowner and businessman, is turned away from the polls when he tries to vote, then flees an angry mob. After Norman flees to New York City, the mob turns to Perry. They burn churches, homes and businesses, sending hundreds of Black people fleeing what the Orlando Morning Sentinel described as a “gruesome cremation scene.” Ocoee then becomes a sundown town with no Black residents until the late 1970s.

June 2, 1924:

The Indian Citizenship Act grants Native Americans the right to vote. Some states ignore the law.

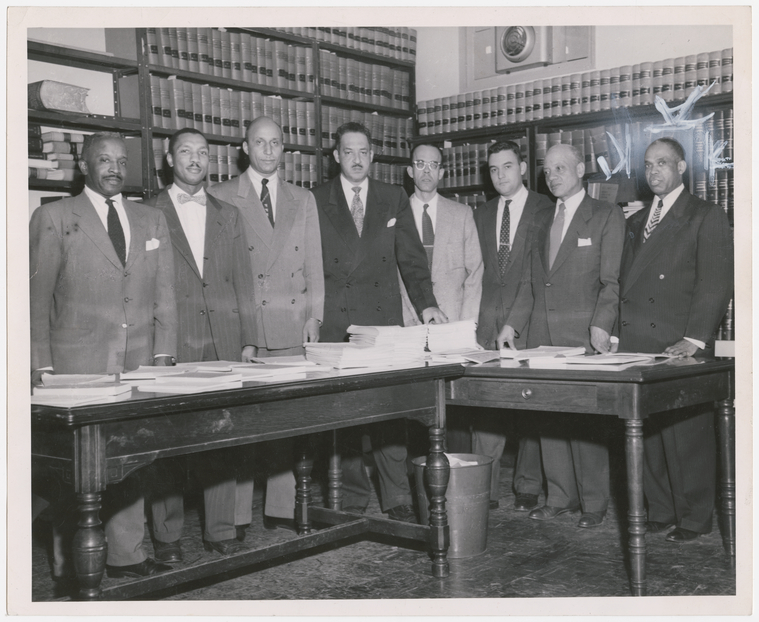

March 20, 1940:

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund is incorporated as the legal arm of the NAACP with Thurgood Marshall as its director.

June 20, 1940:

Amid a domestic terror campaign aimed at anyone even suspected of involvement with the newly-organized NAACP chapter, Elbert Williams is kidnapped and lynched in Brownsville, Tennessee, because of his efforts to register Black voters. The NAACP considers him “the first NAACP member murdered for his civil rights activity.”

July 17, 1946:

Maceo Snipes, a World War II veteran, is murdered by the Ku Klux Klan after he is the only Black person to vote in the Democratic primary in Taylor County, Georgia. No one is ever charged.

July 12, 1947:

Thurgood Marshall and his team win the case of Elmore v. Rice that challenges South Carolina’s whites-only Democratic Party primaries. But this was a pyrrhic victory. As one scholar notes, “The elements of reading,writing, and interpreting the Constitution were still in effect, as well as the poll tax, which was not repealed until 1952. So, while there was a victory in the ability to vote, the assurance of actually being able to vote without conditions was not.” As for George A. Elmore, the once prosperous community leader – political activist, photographer, and proprietor of a five-and-dime store, two liquor stores, and a taxi service – became a tragic figure. White vendors refused to sell him goods for his stores; the KKK burned crosses on his property and sent his family photos of lynchings; and his wife suffered a nervous breakdown that required confinement to a mental institution for the rest of her life. Elmore was pretty much a pauper when he died in 1959 at the age of 53.

Oct. 29, 1947:

President Truman’s Committee on Civil Rights, established by Executive Order 9808 the previous December, issues “To Secure These Rights,” a report outlining a modern vision of the federal government’s role in securing civil rights. The 15-member committee includes two Black luminaries: Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, a lawyer from Philadelphia who was the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in the U.S.; and Channing H. Tobias, a clergyman, educator and senior official with the YMCA and the NAACP who had previously held an appointment by President Franklin Roosevelt.

Sept. 8, 1948:

Dover Carter, the 41-year-old president of the NAACP branch in Montgomery County, Georgia, is savagely beaten while transporting Black voters to and from the polls. His colleague in NAACP efforts, Isaiah Nixon, age 26, is fatally shot after he votes that day. As reported by the Associated Press (AP), Nixon had gone to the polling place and asked if he could vote. He was told “that he had the right to vote but was advised not to do so.” He votes. Hours later, two white men, the Johnson brothers, drive out to his farm and, with Nixon’s family watching, fatally shoot him.

January 10, 1957:

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., is founded in Atlanta, Georgia. Its mission is to coordinate and expand nonviolent civil rights work following the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Sept. 9, 1957:

President Dwight Eisenhower signs the Civil Rights Act of 1957 into law, noting it is only the second federal civil rights law enacted in 85 years. Eisenhower notes “The new Act also deals significantly with that key constitutional right of every American, the right to vote without discrimination on account of race or color.” He points out that particular provisions offer “great promise of making the Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution fully meaningful.” The law establishes the Civil Rights Division in the Justice Department and an independent, bipartisan Civil Rights Commission to recommend policy related to voting rights, among other matters. The commission’s input will later influence the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

December 1959—April 1963:

After Black Tennesseans in Fayette and Haywood counties win a lawsuit against the local Democratic Party for denying them the right to vote, the white power structure retaliates. The KKK terrorizes. Merchants refuse to sell them goods. Doctors withhold medical services. And landowners evict more than 400 Black families who had worked the land as sharecroppers. Black property owners let them live in tents on their land. Justice Department lawsuits against landowners lead to injunctions barring interference in the voting rights of those evicted.

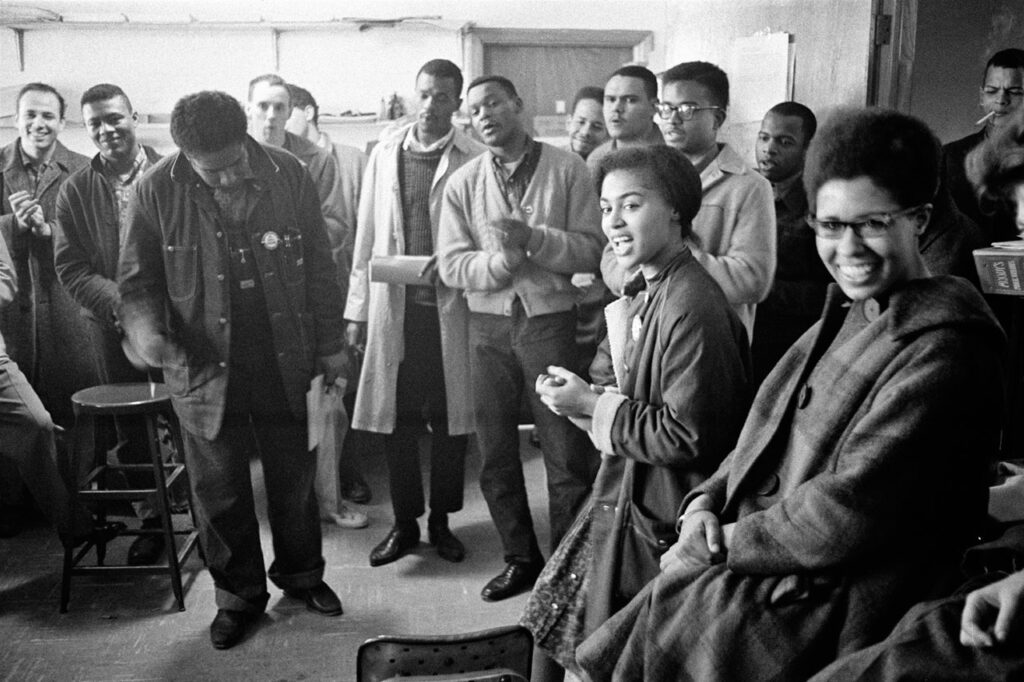

April 15, 1960:

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) is founded.

May 6, 1960:

With the stroke of President Dwight Eisenhower’s pen, the Civil Rights Act of 1960 becomes law. It is meant to protect Black Americans’ right to vote by requiring local officials to keep voting records and making it a crime to block someone from registering to vote. But it does not eliminate literacy tests, poll taxes, or the intimidation and violence that keep many Black people from casting ballots.

March 29, 1961:

The 23d Amendment is ratified, granting Washington, D.C. residents the right to vote for president and vice president.

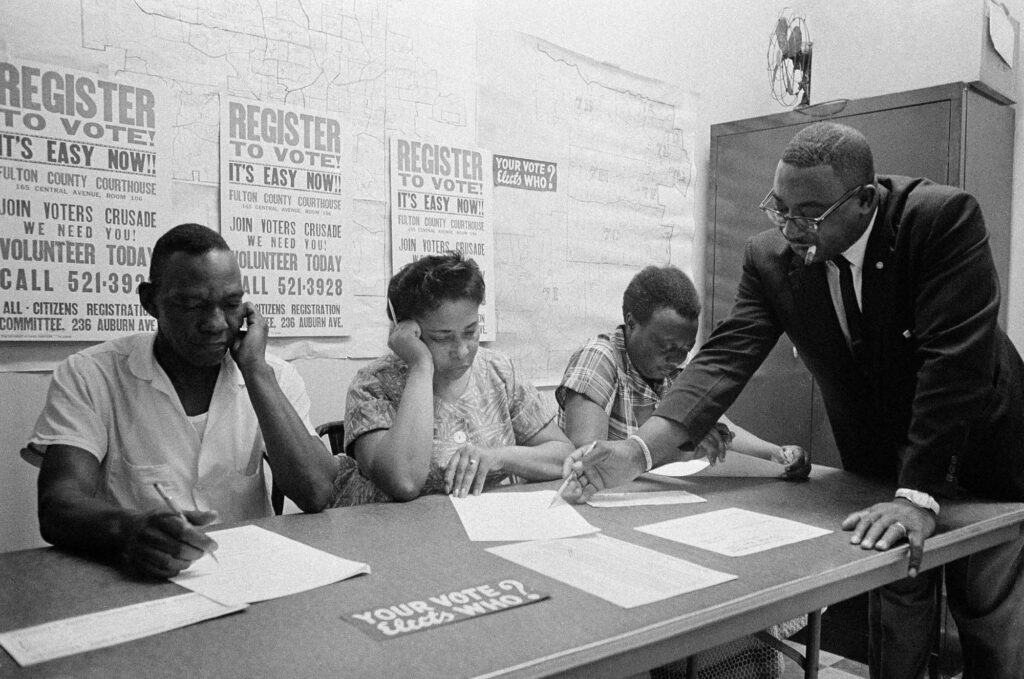

Aug. 27, 1962:

A sharecropper named Fannie Lou Hamer attends her first SNCC meeting in Sunflower County, Mississippi, and learns for the first time that she has a right to vote. Four days later, she and 17 others travel to Indianola, the county seat, to register to vote. Most, including her, fail the literacy test and are turned away. After harassment, a drive-by shooting, losing her job, and being forced to move to another county, she passes on the third try on Jan. 10, 1963. But she is turned away again because she does not have money to pay the poll tax.

June 11, 1963:

As young children are brutalized by dogs and fire hoses in Birmingham, Alabama, during civil rights campaigns, President Kennedy takes to the airwaves to propose a comprehensive civil rights bill that ends segregation in public places and ensures equal access to education. But it would also reflect his view that every American should be able to vote “in every election without interference or fear of reprisal.” His bill would give the attorney general the authority to file lawsuits on behalf of people who had denied the right to vote. “Next week,” he tells the nation, “I shall ask the Congress of the United States to act, to make a commitment it has not fully made in this century to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.”

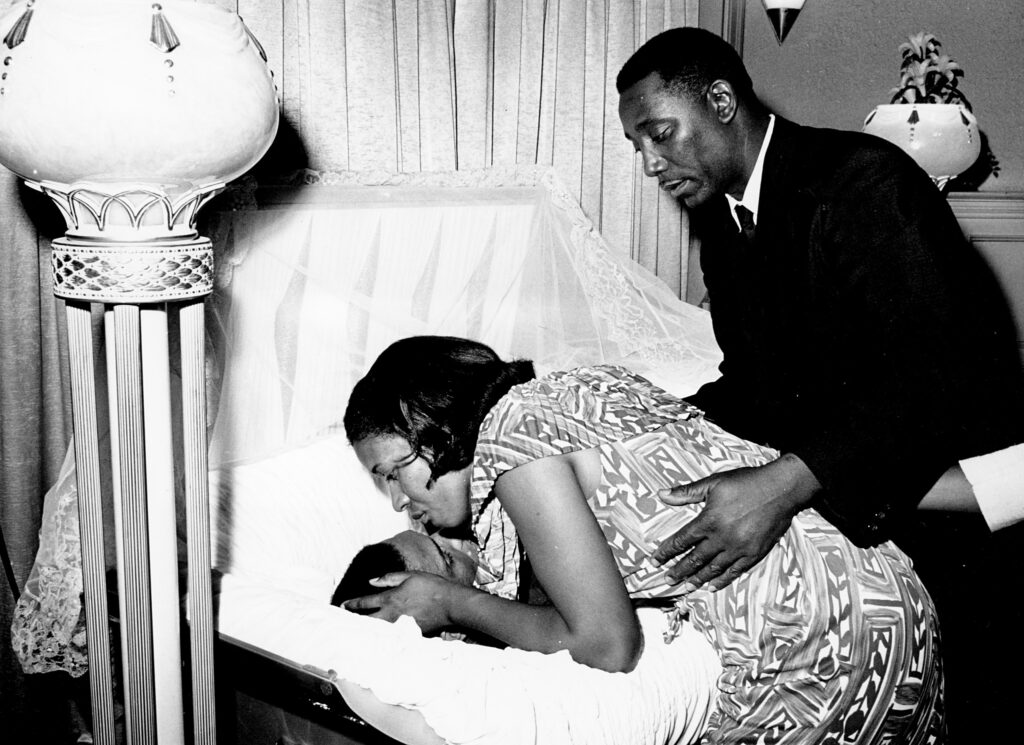

June 12, 1963:

Hours after President Kennedy’s civil rights speech, Medgar Evers, the NAACP’s field secretary in Mississippi and a World War II veteran, is assassinated in the driveway of his home in Jackson.

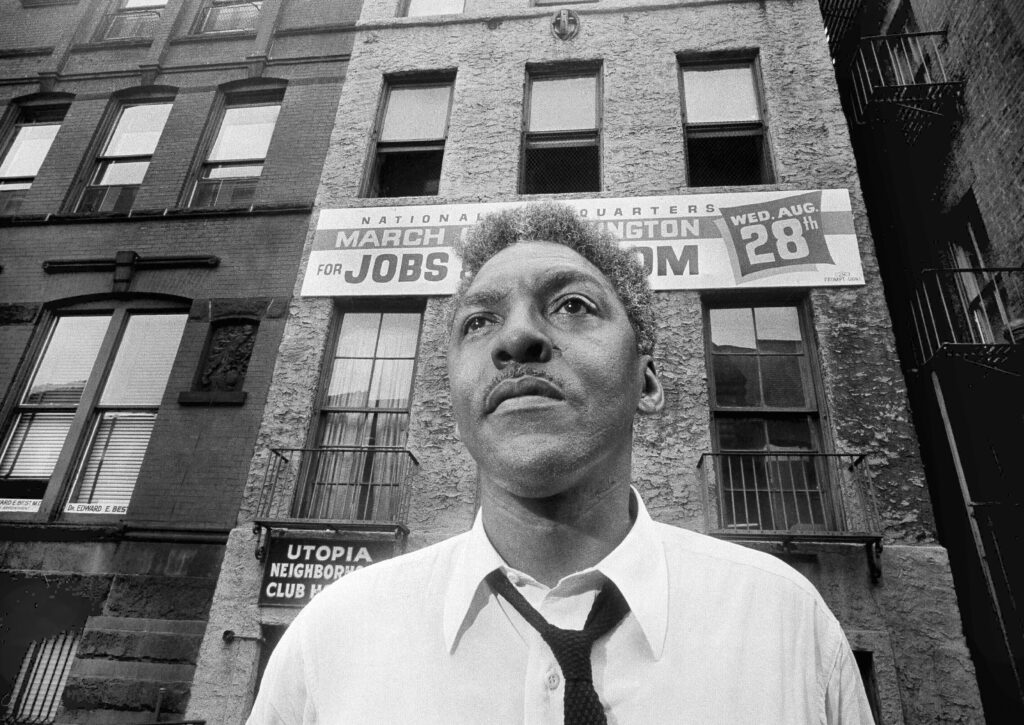

Aug. 28, 1963:

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom draws 250,000 people to the Lincoln Memorial. While it is meant to persuade Congress to enact the civil rights bill proposed by President Kennedy five months before his assassination, many of those gathered carry signs demanding voting rights. Several speakers address the matter directly. Roy Wilkins, the executive secretary of the NAACP, says: “Our march is a march for civil rights — including the right to vote — and civil liberties.” Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers, says, “The job question is crucial, but so is the right to vote — for the ballot box is the one place in America where we are supposed to be equal.” The list of 10 demands read to the crowd by march organizer Bayard Rustin includes this: “The elimination of all restrictions on the right to vote.”

September 1963:

CBS begins a 30-minute nightly newscast on Sept. 2 and NBC follows on Sept. 9. ABC continues to offer 15 minutes of nightly news until 1967. In that first CBS broadcast, the lead piece is about Gov. George Wallace’s refusal to allow Black students to enroll at the University of Alabama. The civil rights movement is reaching its peak.

Nov. 27, 1963:

Five days after President John F. Kennedy is assassinated in Dallas, Texas, his successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson, addresses Congress, saying: “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long.”

Jan. 23, 1964:

The 24th Amendment is ratified, outlawing poll taxes in federal elections. (It will be another two years before the Supreme Court rules that poll taxes are unconstitutional in state and local elections.) Of the old Confederacy, only Texas and Florida ratify the 24th Amendment before it becomes the law of the land. A few states symbolically do so decades later, including Mississippi in 2020.

July 2, 1964:

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. While most of the focus is on what this means for Black people’s access to public accommodations like hotels, restaurants, recreational facilities, and public transportation, the law also bans discriminatory practices in voter registration.

June 15, 1964—Aug. 31, 1964:

The Mississippi Freedom Summer Project, spearheaded by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the NAACP, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), attracts a mostly-white group of about 1,000 college students to Mississippi to work with thousands of Black Mississippians to register Black voters. The state has the lowest percentage of Black voters in the United States. The workers convince about 17,000 people to register, but fewer than 2,000 are able to navigate the hurdles of literacy tests and poll taxes. The Freedom Summer energy inspires Fannie Lou Hamer and others to form the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the political system. But the toll is high. According to the National Archives, “It is believed that 1,062 people were arrested, 80 Freedom Summer workers were beaten, 37 churches were bombed or burned, 30 Black homes or businesses were bombed or burned, four civil rights workers were killed, and at least three Mississippi African Americans were murdered because of their involvement in this movement.” The June 21, 1964, murder of three of them – James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner – brings worldwide attention to the voting rights struggle and President Johnson’s administration to act.

January—March 1965:

Buoyed by the 1964 Civil Rights Act, grassroots voting rights activists in Selma, Alabama (Dallas County), and neighboring communities ramp up efforts that had begun in 1963. They are supported by SNCC, the SCLC, and the NAACP. Although Black citizens make up nearly half the population in Dallas County, they are routinely denied registration through intimidation, unfair tests, and violence. The campaign gains national urgency after the fatal shooting of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a young, unarmed Black man who was trying to protect his family during a peaceful march in neighboring Marion, Alabama, on Feb. 18. His death becomes a rallying cry for justice.

March 7, 1965:

Hundreds of peaceful protestors are brutally attacked by state troopers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on a day that will become known as “Bloody Sunday.” John Lewis, then a young activist, has his skull cracked in the melee. Americans watch the violence unfold on television, sparking widespread outrage and drawing thousands more people — Black and white, young and old, clergy, students, union members, Hollywood stars and ordinary citizens — to join the demand that the right to vote be protected for all Americans. The third attempt to march the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital, begins March 21 with an escort of Alabama National Guardsmen (under federal control), the FBI, and U.S. marshals. They arrive March 21 and are joined by more than 20,000 others for a rally the next day at the steps of the Alabama statehouse.

March 15, 1965:

In a nationally-televised address, President Lyndon B. Johnson tells a joint session of Congress that he wants a voting rights law. He makes reference to God as he closes his speech. “God will not favor everything that we do. It is rather our duty to divine His will. But I cannot help believing that He truly understands and that He really favors the undertaking that we begin here tonight.”

May 17, 1965—Aug. 4, 1965:

Congress acts. The Senate gets a bill, S. 1564, on March 17; the House gets a bill, H.R. 6400, on March 19. The Senate passes its bill by a vote of 77-19 on May 26. The House passes its bill by a vote of 333-85 on July 9. After the two chambers reach a consensus, the House votes 328-74 to pass the bill on Aug. 3; the Senate votes 79-18 on August 4. Most of the opposition comes from Southern legislators.

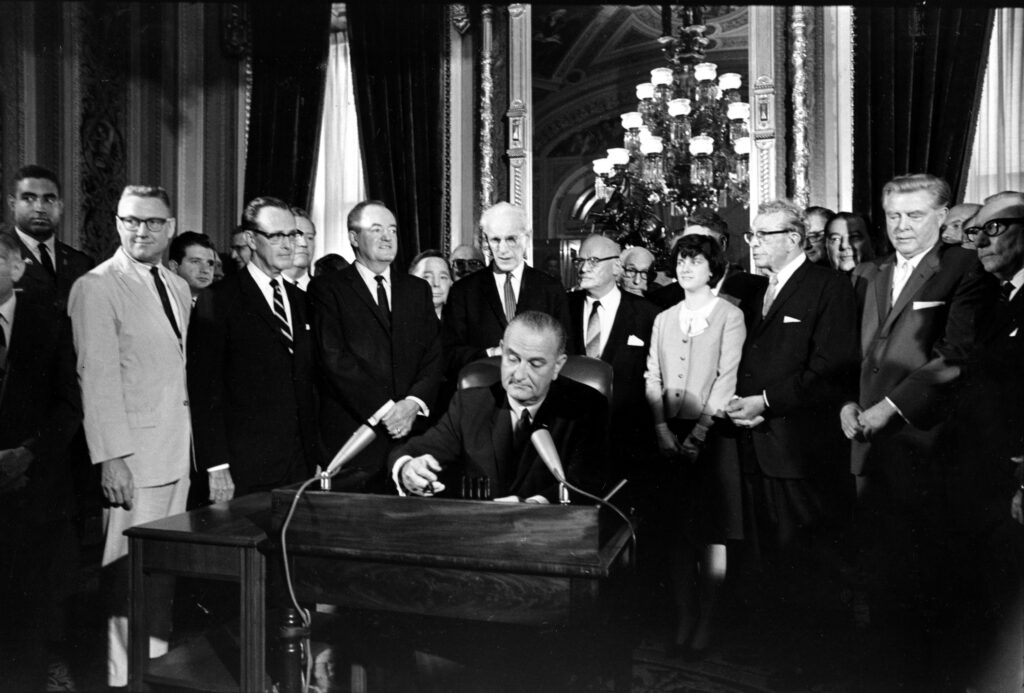

Aug. 6, 1965:

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in a ceremony televised from the Capitol rotunda. With federal oversight and enforcement powers, the government is guaranteeing Black people real access to the ballot for the first time. A promise made 95 years before with ratification of the 15th Amendment is finally a reality. “The vote is the most powerful instrument ever devised by man for breaking down injustice and destroying the terrible walls which imprison men because they are different from other men,” Johnson says during the signing ceremony.

______________________________________________________________________________

This timeline is part of a collaboration between the Associated Press, Black News & Views, and The Amsterdam News. The work is part of the AP Inclusive Journalism Initiative supported by the Sony Foundation.