I had not yet been born in 1948, a year fraught with challenges to the voting potential of Black Americans. Just three years after the United States and its allies had declared victory over fascism and ended World War II, Black Americans were ready to wage a domestic war against racism.

That year was one of martyrdom and heroism. And I did not know until five years ago that my hometown, Conyers, Georgia, was among the many places in the old Confederacy where Black people took stands that have largely been forgotten.

The impending 60th anniversary of the passage of the Voting Rights Act is an appropriate time to begin to remember.

The incumbent Democratic president, Harry S. Truman, imbued many Black people with hope when he announced a civil rights agenda in 1947 and began issuing executive orders in 1948 to desegregate the military and open employment opportunities. He was proposing to put the muscle of the U.S. government behind voting rights laws that in practice had often been no more than words on paper since the 1860s.

In the Deep South, many whites were enraged. Southern Democrats, calling themselves Dixiecrats, fielded their own candidate, the uber racist senator from South Carolina, Strom Thurmond, whose campaign slogan was “Segregation Forever!” In Georgia, Thurmond’s second cousin, Herman Talmadge, was running for governor, vowing to reserve the Democratic primaries for white voters only despite federal rulings in 1945 that declared white primaries unconstitutional.

“If we can’t have a white primary, we want as white a one as we can get,” he said.

Talmadge was cut from the same mold as his unapologetically racist father, the late Gov. Eugene Talmadge, who died during his fourth term in office in 1946. In a radio address, the older Talmadge said, “Wise Negroes will stay away from white folks’ ballot boxes.”

The younger Talmadge considered President Truman’s civil rights agenda “the most dangerous threat to Georgia’s way of life since Reconstruction.”

He failed to see that a sleeping giant was beginning to awaken, spurred by post-war determination and federal court rulings that snipped away at Byzantine traditions that denied Blacks access to the ballot.

In March 1948, the 237 Black registered voters in Conyers – the county seat of a still-rural Rockdale County 25 miles southeast of Atlanta – were making decisions about the first of three elections that year. The three elections were: the spring presidential primary held around the state between March 9 and June 1, the gubernatorial primary on Sept. 8, and the general election on Nov. 2. Those who tried to suppress the Black vote did not resort to violence or convoluted literacy tests. Instead, names of newly-registered voters were printed in the local newspaper.

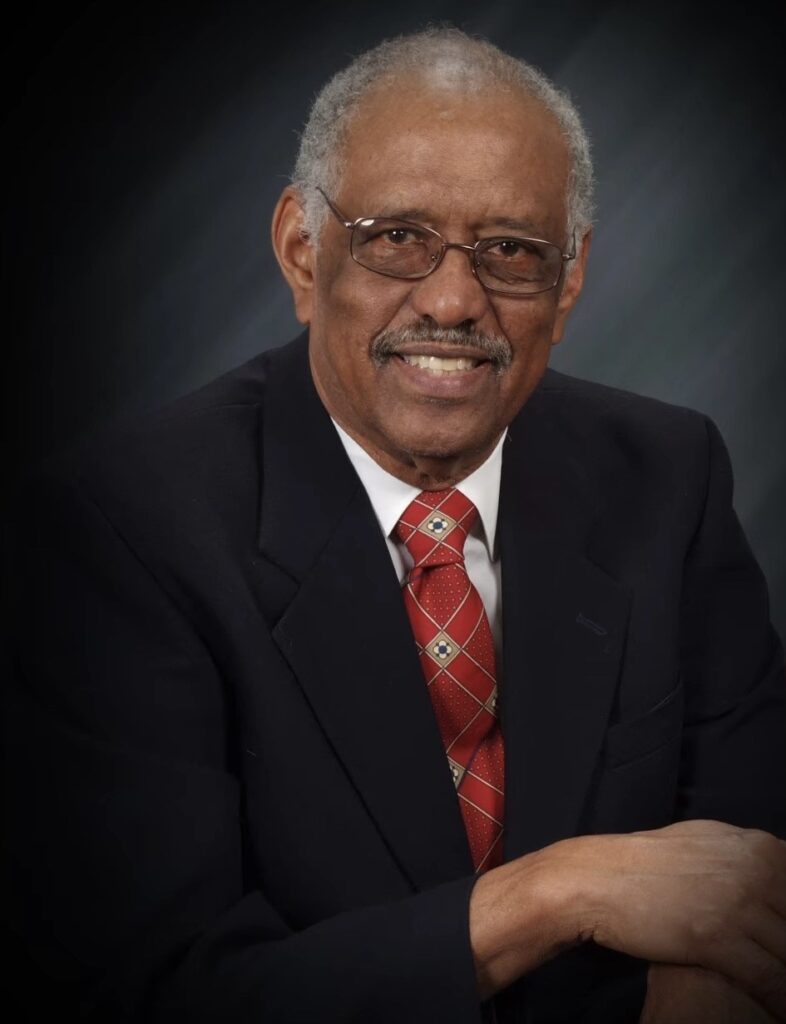

“It was an intimidation thing. That’s why they put it in the paper,” observed Cleveland D. Stroud, who recently turned 89. A revered elder in Conyers now, he broke barriers as an educator, a basketball coach, and the first Black person elected to the City Council.

While some whites didn’t cotton to the notion of Black people voting, others encouraged “their” Blacks to vote in local elections to secure their power.

“Conyers was really ahead of most places as far as [race] relations were concerned,” Stroud said, quickly adding: “Not that they were great, but they were better than in other places.”

In other counties, there was nothing subtle at all. In some places, loyalty oaths were required before a person could vote, such as one that The New Yorker reported on at the start of 1948. “Voters in Johnson County, Georgia, before casting their ballots in the primaries, must swear that they will support racial segregation and the county-unit system, and they must swear that they will oppose Communism, subversive organizations and the Fair Employment Practices Commission. Maybe ‘voters’ is too strong a word for these people. Maybe we should just say disciples.”

NAACP branches and the Atlanta Urban League spearheaded voter registration drives. So did the influential Black newspaper, The Atlanta Daily World, which since 1945 acted in tandem with a network of voting rights activists who included Charlie Darien in Conyers. In response, the Ku Klux Klan paraded, sent threats, and burned crosses throughout rural Georgia to convince Black people that voting = death.

In a widely reported incident, Maceo Snipes, a veteran of the recently-ended World War II, was murdered by Klansmen after he became the only Black person to vote in the Democratic primary in Taylor County on July 17, 1946. That’s about 100 miles south of Conyers. Just eight days later and only 20 miles from Conyers, two married couples, including another World War II veteran, were lynched in Walton County. Though the last known mass lynching in the U.S. was not related to voting, it was part of the aura of terror that guided the footsteps of every Black man, woman and child.

In the couple of weeks leading to the primary, Klansmen repeatedly sought a permit to parade in the heart of Conyers and hold a cross-burning rally on the night of Tuesday, March 23, outside the courthouse where most Black men and women would cast their ballots just hours later on Wednesday. The mayor said he turned them down three times. The governor sent state troopers to monitor the situation.

As reported by the Scott Newspaper Syndicate (SNS), a news service created by the publisher of The Atlanta Daily World: “Tuesday night a cross was burned beside the railroad tracks directly in the center of the Negro community. Another was burned on Highway 20, two miles south of Conyers. A third one appeared already burnt at the Bank of Rockdale. A fourth cross was burned at Honey Creek.”

Then came Wednesday, when “[a] large number of whites were crowded around the Rockdale courthouse all throughout the balloting.”

Despite the threats and the curious crowds, the news service reported: “Early Wednesday morning Negro voters began converging on the attractive Rockdale County Courthouse where separate tables were set up for balloting in the courtroom. A café owner, Raleigh Sessions, volunteered to drive all qualified voters to the polls. Other car owners joined the effort. A large number had voted before noon.”

Black people had defied the Klan.

Their actions, along with those in a few other towns, were widely reported in Black newspapers. In Lawrenceville, about 20 miles north of Conyers, the news service reported that Black people voted “despite an all-night ‘intimidation carnival’ where firecrackers and flares lighted up the skies and a cross was burned in front of the Second Baptist Church.”

Many of the most politically active Black residents in Conyers told the SNS reporter that they had approached primary day without fear and managed to get most of the Black registered voters to the courthouse to cast their ballots. A few others had voted at polls further out in the county.

Gov. Melvin E. Thompson issued a statement praising officials in Conyers and other towns for “taking action to prevent parades of masked men” and urged other parts of the state to follow their example. That many other localities ignored the governor was evident from an editorial in The Atlanta Daily World about the spring primaries.

In Johnson County, according to the editorial, “not one of the 800 registered voters” cast a ballot. In Montgomery County, “only about 20% of the registered Negroes cast ballots in the election, following intimidation through notes of warning found in mailboxes of Negro citizens of the county.” Because state officials claimed their hands were tied, the paper said, the only solution was President Truman’s civil rights proposals.

Reflecting on those days, Stroud said, “It took more courage to [vote] then than now. They really put their livelihood on the line by registering to vote because many times they would lose their jobs if they did.”

Sometimes their lives were on the line too.

With the primary in September and the general election in November, terror campaigns and violence continued. Dove Carter, the 41-year-old president of the local NAACP branch in Montgomery County, was savagely beaten while transporting Black voters to and from the polls on Sept. 8. He later fled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His colleague in NAACP efforts, Isaiah Nixon, age 26, was fatally shot after he voted on Sept. 8. As reported by the Associated Press (AP), Nixon had gone to the polling place and asked if he could vote. He was told “that he had the right to vote but was advised not to do so.” He voted. Hours later, two white men, the Johnson brothers, drove out to his farm and, with Nixon’s family watching, fatally shot him.

Like so much of what is now looked upon as historic local acts that together comprised the civil rights movement, this 1948 episode in my hometown was pretty much unknown to later generations. Stroud recalls that his grandmother, Janie Gilstrap, spoke of the time that Raleigh Sessions drove her to the courthouse to vote. As a child, I knew some of the leaders of what might be viewed as a 1948 precursor to “souls to the polls” engagement efforts common today. But they were just old folks to me. We kids knew to respect them, but we did so because they were old not because they had been through the storms.

“They didn’t talk about it that much,” Stroud said. “I guess they were trying to forget it, you know.”

Between the end of World War II and when I started first grade in 1961, they – and in some cases, their children, including Stroud – had bucked the status quo by organizing voting leagues, civic groups, and a parent-teacher association. They forced the county to build a modern school building for Black children in 1950 – the school I later attended from first through eighth grades. Some of those activists from 1948 were still around when the county began to desegregate the schools in waves, first in 1965 and again in 1968. But most of us had no idea that they were living icons of Black history, our county’s very own profiles in courage.

This article is part of a collaboration with the Associated Press, Black News & Views, and The Amsterdam News. The work is part of the AP Inclusive Journalism Initiative supported by the Sony Foundation.

_______________________________________________________