Sixty years after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act on Aug. 6, 1965, Black Americans are facing diluted advances and fighting some of the battles already won.

That is the collective view of advocates whose work is tied to making sure Black people can cast ballots, one of the most important rights afforded to individuals. They mention a White House that often equates diversity with unconstitutionality and a political climate that some Black Americans say feels dangerous.

“The power dynamic has changed,” Cornell William Brooks, former NAACP president, civil rights lawyer, and professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School, told contributor Allison Davis. “We are in a place where we are literally litigating what it is that was long-settled law and trying to secure victories that we thought we already had,” Brooks said.

The VRA, which outlaws discrimination in voting, came about after decades of resistance, prodding of elected officials, and protests turned violent, like “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965. The backlash against voting rights began immediately after the VRA was passed, said Derrick Johnson, current president of the NAACP.

RELATED: The complete Voting Rights Act project

In 2013, the Supreme Court gutted the VRA by throwing out the provision that required jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to get federal approval of changes in voting procedures. Since then, states have passed dozens of restrictive voting laws, 19 laws in 2024 alone, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Restrictive laws are measures that heighten the bar for someone to be admitted into a polling site, such as traditional identification — a requirement that can be problematic for older Black people born at home in the rural South who might not have birth certificates. In the Supreme Court’s next term starting in October, a case that could affect majority Black Congressional districts will be re-argued.

“What we’re seeing now is an aggressive shift by individuals who are in power to try to prevent eligible citizens, as guaranteed by the Constitution, to exercise their right to vote and their ability to select individuals of their choice,” Johnson said.

Those who worked in the office of late U.S. Rep. John Lewis, one of the “Big Six” organizers of the 1963 March on Washington and a longtime voting rights advocate, said if Lewis were alive today, he would inject some realism into the current political state of affairs.

“It boils down to staying the course,” Linda Earley Chastang, Lewis’ former chief of staff, told Allison Davis. “So if your course is correct, then you stay that course.”

Earley Chastang said if she was troubled about some setback in policy or civil rights, Lewis would put her in check.

“What he would say is, ‘Linda, it’s going to be OK. We’ve been there before. It’s been done before. We’re moving in the right direction, we’re just not moving quickly, but we will get there.’ “

“Congressman Lewis would tell us, ‘It’s going to be all right,’ ” Michael Collins, another former chief of staff to Lewis, told Black News & Views. Continuing as Lewis, he said: “ ‘It’s going to be difficult, we’re going to see some difficult times, we’ve got to take care of each other, we’ve got to lean on each other, we’ve got to stand up for one another, but it’s going to be all right and this time shall pass.’ “

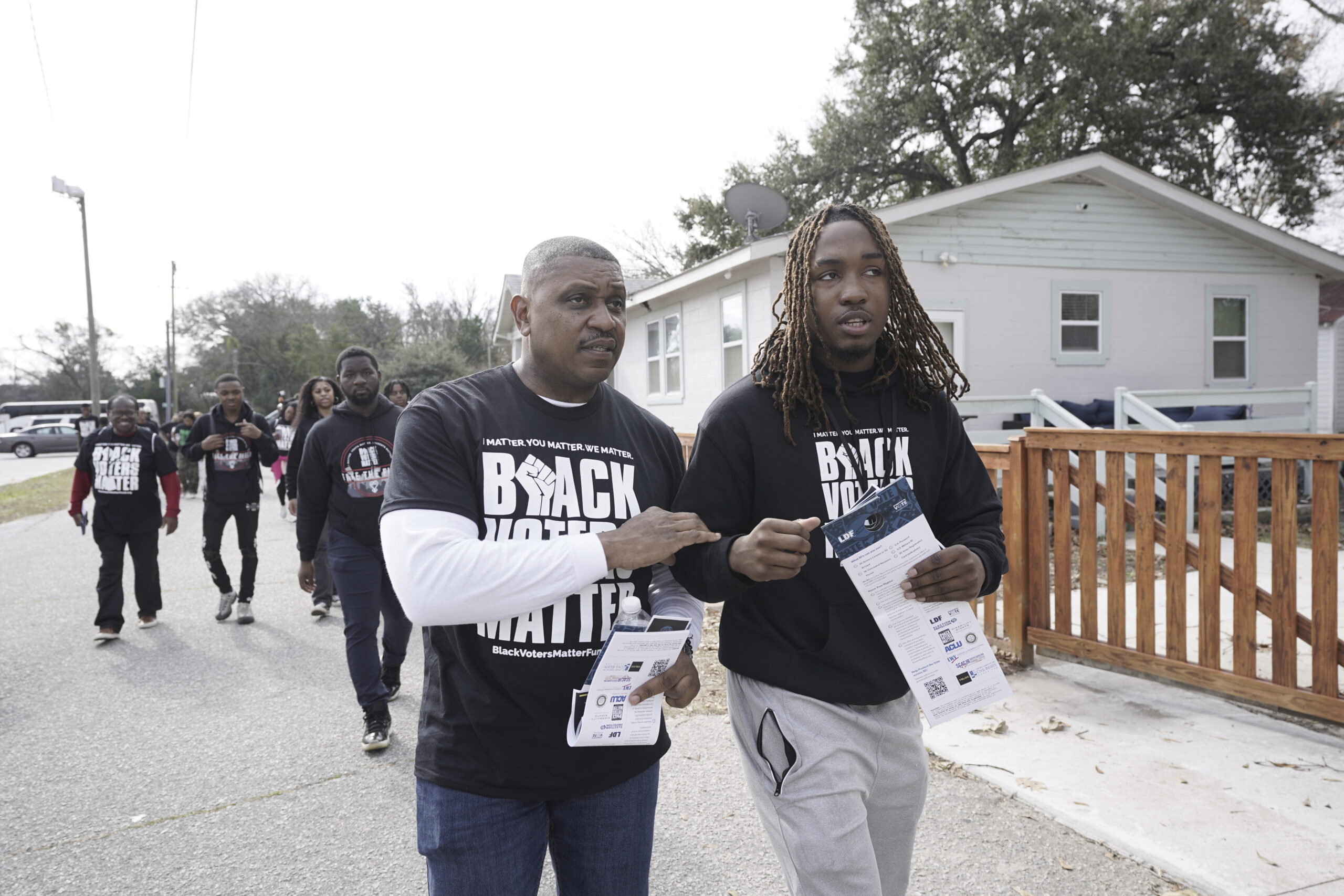

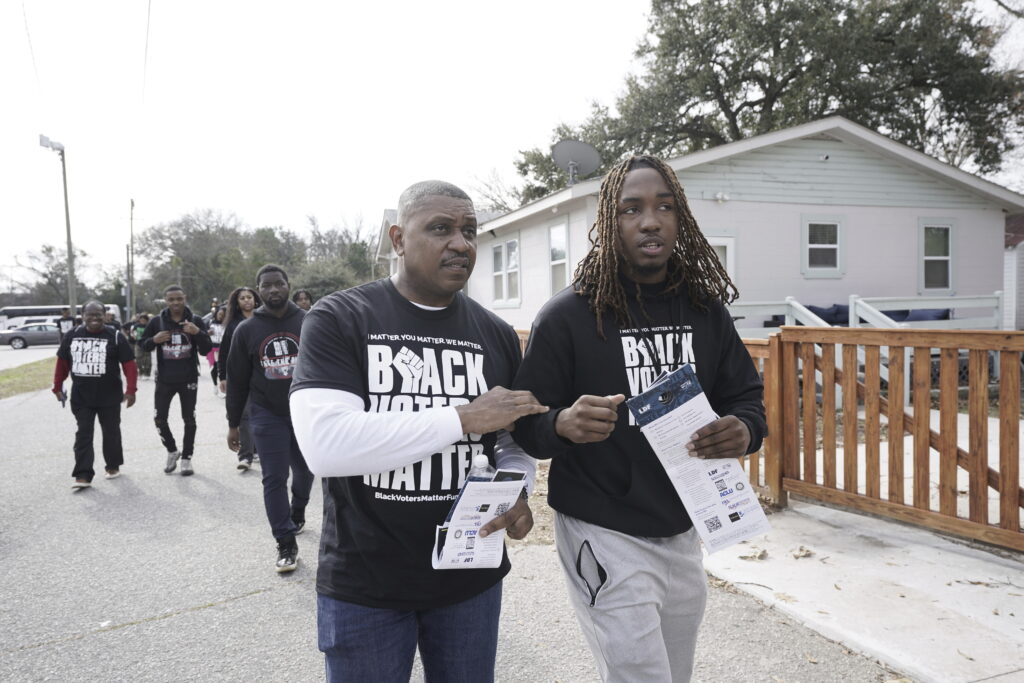

As for the future, young voters told contributor Tadi Abedje that they feel a responsibility to make sure they show up at the polls.

“I feel like voting means to me having a voice to continue to speak what my ancestors built upon,” said Ryann Dawkins, a recent graduate from North Carolina A&T University. “And I feel it’s blatant disrespect for me not to go out and vote and be an educated voter,” she said.

This piece is part of a collaboration between the Associated Press, Black News & Views, and The Amsterdam News. The work is part of the AP Inclusive Journalism Initiative supported by the Sony Foundation.