SELMA, Ala. (AP) — President Joe Biden is set to pay tribute to the heroes of “Bloody Sunday,” joining thousands for the annual commemoration of the seminal moment in the civil rights movement that led to passage of landmark voting rights legislation nearly 60 years ago.

The visit to Selma, Alabama, on Sunday also is an opportunity for Biden to speak directly to the current generation of civil rights activists. Many feel dejected because Biden has been unable to make good on a campaign pledge to bolster voting rights and are eager to see his administration keep the issue in the spotlight.

Biden intends to use his remarks to underscore the importance of commemorating Bloody Sunday so that history can’t be erased, while making the case that the fight for voting rights remains integral to delivering economic justice and civil rights for Black Americans, according to White House officials.

This year’s commemoration also comes as the historic city of roughly 18,000 is still digging out from the aftermath of a January EF-2 tornado that destroyed or damaged thousands of properties in and around Selma.

Before Biden’s visit, the Rev. William Barber II, a co-chair of Poor People’s Campaign, along with six other activists wrote to Biden and members of Congress to express their frustration with the lack of progress on voting rights legislation. They also urged Washington politicians visiting Selma not to sully the memories of the late civil rights activists John Lewis, Hosea Williams and others with empty platitudes.

“We’re saying to President Biden, let’s frame this to America as a moral issue, and let’s show how it effects everybody,” Barber said in an interview. “When voting rights passed after Selma, it didn’t just help Black people. It helped America itself. We need the president to reframe this: When you block voting rights, you’re not just hurting Black people. You’re hurting America itself.”

Few moments have had as lasting importance to the civil rights movement as what happened on March 7, 1965, in Selma and in the weeks that followed.

Some 600 peaceful demonstrators led by Lewis and Williams had gathered that day, just weeks after the fatal shooting of a young Black man, Jimmie Lee Jackson, by an Alabama trooper.

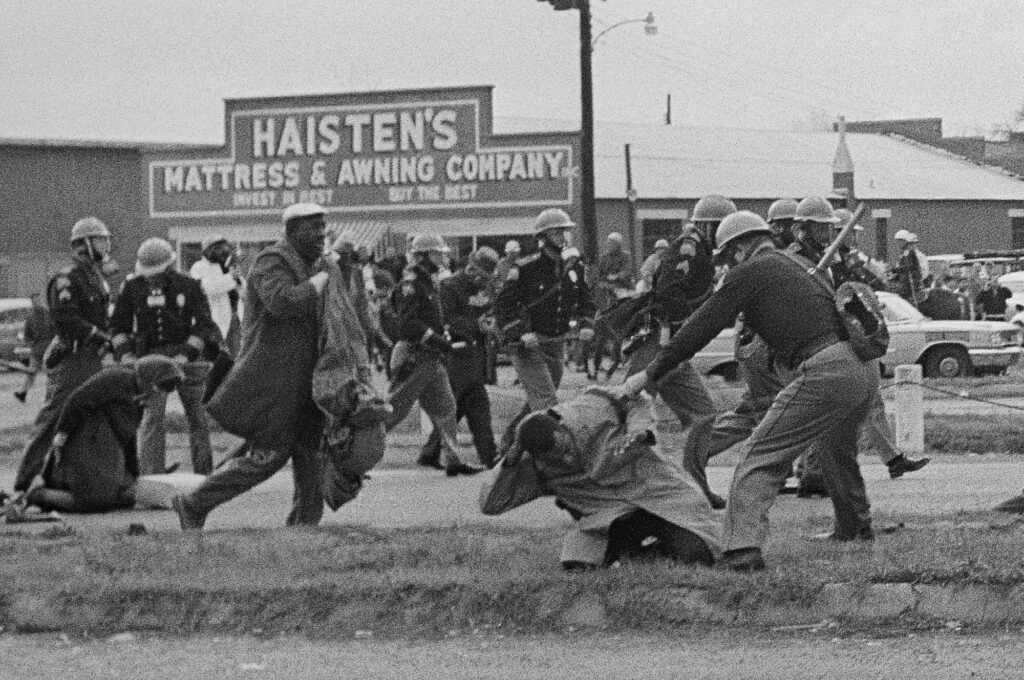

Lewis, who would later serve in the U.S. House representing Georgia, and the others were brutally beaten by Alabama troopers and sheriff’s deputies as they tried to cross Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge at the start of what was supposed to be a 54-mile walk to the state capital in Montgomery, part of a larger effort to register Black voters in the South.

The images of the police violence sparked outrage across the country. Days later, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. led what became known as the “Turnaround Tuesday” march, in which marchers approached a wall of police at the bridge and prayed before turning back.

President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced the Voting Rights Act of 1965 eight days after Bloody Sunday, calling Selma one those rare moments in American history where “history and fate meet at a single time.” On March 21, King began a third march, under federal protection, that grew by thousands by the time they arrived at the state capital. Five months later, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

As a 2020 White House candidate, Biden vowed to pursue sweeping legislation to bolster protection of voting rights, .

Biden unveiled his legislation in 2021 — naming it the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. It included provisions to restrict partisan gerrymandering of congressional districts, strike down hurdles to voting and bring transparency to a murky campaign finance system that allows wealthy donors to bankroll political causes anonymously.

It passed in the then-Democratic-controlled House, but failed to garner the 60 votes needed to win passage in the Senate. With Republicans now in control of the House, passage of such sweeping legislation is highly unlikely.

Keisha Lance Bottoms, director of the White House office of public engagement, said Biden understands civil rights activists’ anger over the lack of progress.

“He’s frustrated,” she said. “But it doesn’t mean we have to stop. It doesn’t mean we stop pushing in the way that then 25-year-old John Lewis led 600 marchers across that bridge in Selma.”

Civil rights activists say the Biden administration can do more on the issue.

Two years ago on the day of the annual Bloody Sunday commemoration, Biden issued an executive order directing federal agencies to expand access to voter registration, called on the heads of agencies to come up with plans to give federal employees time off to vote or volunteer as nonpartisan poll workers, and more.

But many federal agencies are lagging in meeting the voting registration provision of Biden’s order, according to a report published Thursday by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

Only three of 10 agencies reviewed — the departments of Interior, Treasury and Veterans Affairs — were rated on track in integrating voter registration services into their everyday interactions with the public, according to the report.

The group says if agencies fully implemented voter registration efforts laid out in the executive order, it would generate an additional 3.5 million voter registration applications annually.

“We are two years into this executive order and two years into this administration, and agencies have had plenty of time for for evaluation and deliberation,” said Laura Williamson, associate director for democracy at the left-leaning group Demos.

Vice President Kamala Harris said in a statement that the administration will continue to implement the order while pressing Congress to act on broader voting legislation. “If we are to truly honor the legacy of those who marched in Selma on Bloody Sunday, we must continue to fight to secure and safeguard the freedom to vote,” Harris said.

Selma officials hope Biden will also address the January tornado that devastated the city and laid bare issues of poverty that have persisted in Selma for decades.

Biden approved a disaster declaration and agreed to provide extra help for debris cleanup and removal, a cost that Selma Mayor James Perkins said the small city could not afford on its own. Perkins said Selma still needs more help.

“I understand other communities our size and our demographics have similar challenges … but I don’t think anyone can claim what Selma has done for this nation and the contributions that we made to this nation,” he said.