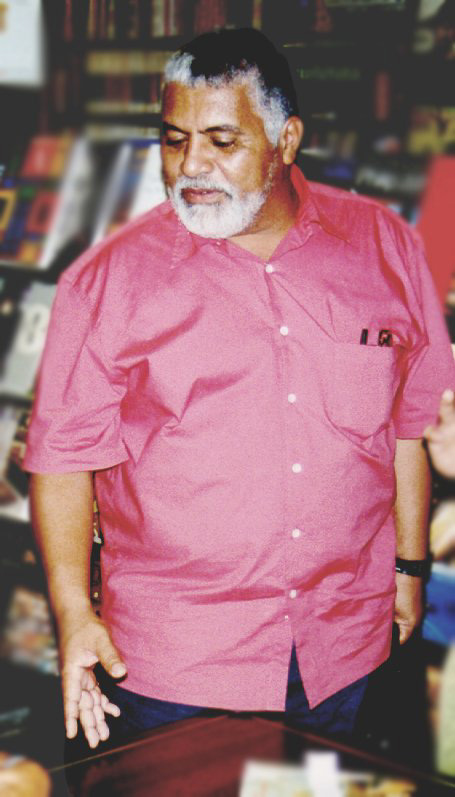

RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil – The death of investigative journalist Tim Lopes in 2002 changed Brazilian journalism forever.

Lopes grew up poor in a Rio de Janeiro favela and worked his way up to leadership at Globo television—rare for a Black journalist back then. The versatile reporter became widely known for his undercover investigations that exposed wrongdoings against the impoverished. On June 2, 2002, while reporting undercover in a favela, Lopes was kidnapped, tortured, and killed by drug traffickers.

His brutal death inspired his journalism colleagues to unite and create ABRAJI, the Associacao Brasileira de Jornalismo Investigativo or Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalists. Since its founding 21 years ago, ABRAJI has become Brazil’s most influential and prestigious journalism organization, and maintains a mission to train and protect journalists and the public’s right to information.

To achieve this, ABRAJI organizes the International Congress of Investigative Journalism in São Paulo, Brazil, every June. From June 29 until July 2 of this year, more than 1000 of Brazil’s best journalists met in São Paulo for four days of workshops that included 107 activities and 317 panelists.

This year, ABRAJI invited National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) President Dorothy Tucker, investigative reporter with CBS Chicago, and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and NABJ member Wesley Lowery as two of its16 distinguished international guests. The guest panelists from around the world this year came from the United States, Mexico, Colombia, El Salvador, Uruguay, Nigeria, Peru, France, the United Kingdom, and Russia. Lowery and Tucker participated in what organizers say was ABRAJI’s most diverse in-person conference.

Tucker took part in panels on investigative journalism in television and on Black women in journalism. During her investigative journalism panel, she shared an investigative journalism piece in which she found that Black women in Chicago suffered the most from violence in the city. Although Tucker will soon end her two-year run as NABJ’s president, she hopes that future NABJ conferences will, like ABRAJI, invite international journalists as participants.

“For my panel, they had simultaneous interpretation. I would love to see something like that at NABJ,” said Tucker, an investigative journalist for CBS2 WBBM-TV Chicago. “[NABJ] doesn’t invite journalists from around the world to participate in the conference. We’ve had visiting journalists from Africa and Colombia, but I’ve never known us to put them on a panel.”

Despite ABRAJI’s origins, the ABRAJI Congress found itself with a diversity problem in 2019. More than half of Brazil’s 200 million people identify as Black. But that year, only 11 percent of its speakers identified as non-white. With non-white speakers at 34 percent, Abraji’s 18th annual conference was its most diverse.

“If I had walked into an IRE [Investigative Reporters and Editors meeting] and seen the level of diversity that I saw at ABRAJIi, I would be impressed,” Lowery said.

For Lowery, the ABRAJI Congress differed significantly from American journalism conferences that tend to pack in the programming.

“It felt to me like fewer sessions were happening at the same time,” Lowery said. “[In the U.S.], it feels like you are in a bunch of rooms with five people. This felt like every conversation included a sizable portion of the conference.”

In 2016, Lowery won the Pulitzer Prize with a Washington Post reporting project that surveyed statistics of deaths of Black Americans by police. As in the United States, Brazil’s Black population disproportionately suffers from police and gun violence. From 2015 to 2020, the number of people killed by police tripled from more than 2,000 to more than 6,000. Experts estimate that 80 percent of the victims are Black. With Lowery’s expertise in covering the Black Lives Matter movement and investigating police killings, his Q&A proved popular among young Afro-Brazilian journalists, many of whom report on favela communities.

“I liked how he talked about the differences in the experiences of Black journalists and white journalists,” said Agnes Sofia Guimarães, a young Afro-Brazilian journalist attending the conference for her third time.

Guimarães noted that Black journalists in Brazil are more likely to fall into communications and public relations work because well-paid work in traditional journalism is difficult to attain, and white journalists have the upper hand. She is happy to see the diversity increasing at the conference, but she also wants Black journalists to participate on panels outside the race theme.