In the years following the Civil War, some of the most vulnerable people were Black seniors who survived slavery. There was no social welfare support or government programs to help meet the long-term care (LTC) needs of this poor and aged population.

But there were Black churches, social and civic organizations, and Black people, most with little or no means, who were among the first to rally and respond to their needs, providing shelter and other safety nets. They were led by people like anti-slavery hero Harriet Tubman, who in her seventies built a home for Black elders on the property she owned in Auburn, New York.

“After slavery, we [Black people] came together to take care of our poor and elderly, usually with support from Black churches and mission organizations. This was kind of the starting place for our nursing homes. It’s a simple story, and at the same time, it is unique,” says Steven Nash, president and CEO of the Stoddard Baptist Home Foundation serving mostly Black seniors in Washington, D.C., and Maryland. Stoddard was founded on May 8, 1890, and is the longest serving Black-owned and operated nursing home in the United States, Nash said.

Today, more than ever, Nash said, he and other Black providers might look for inspiration to those nursing home pioneers, as they struggle to survive within a long-term care industry that is reeling in COVID’s wake. Care providers for mostly low-income elders of color face even greater challenges than their predominantly white counterparts, because of woefully inadequate Medicaid reimbursements, staffing shortages, and other constraints. But somehow, decades, and even a century ago, many of those early purveyors of tender loving eldercare persevered through their little-known chapter of Black history.

How and where they managed to provide decent care is not well known. But a patchwork history reveals that Black people and the organizations they represented found a way forward, establishing some of the first places to protect their elders from neglect. As aid and homes for white elders emerged from 19 th century “poorhouses,” government-run institutions that housed the destitute, racial segregation hastened the need to create places that never existed for Black adults as they aged. Iris Carlton-LaNey, Ph.D., a Black social welfare historian, calls the places they created “parallel organizations.”

“These were people who were busy doing what was needed, rather than thinking about how to let others know about what they were doing,” says Carlton-LaNey of those focused on the immediacy of social welfare work in support of Black seniors and indigent people. She says not much has changed.

“Even today, as African Americans, we tend to concentrate on what has to be done right now, not on the history being made or about telling our story,” adds Carlton-LaNey, professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill School of Social Work.

One of those pioneers who used social welfare work to help Black seniors and the poor was Eliza Goff.

Then and now

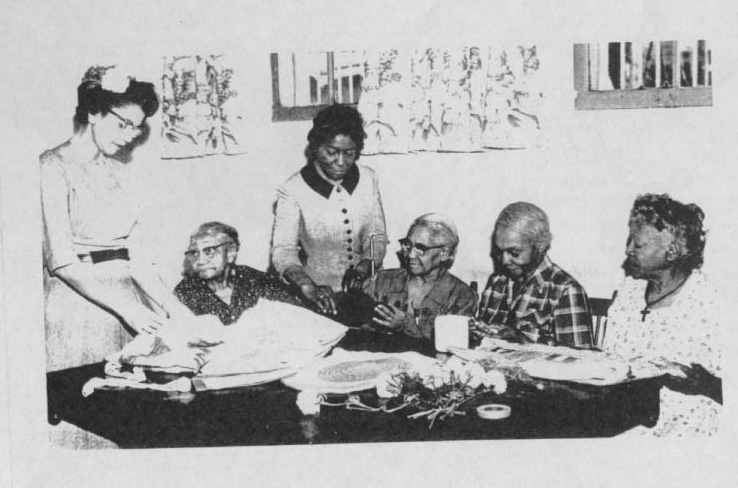

In 1886 as a domestic worker, Goff created the Alpha Home for Aged Colored Women in Indianapolis, Indiana, on land she convinced her employer to donate. Like Goff, the small home’s first residents were Black women who had survived enslavement. By 1928, the home began to admit men.

Keeping the doors of Alpha Home open was a community affair. The local newspaper of the day would announce events that were the home’s financial lifeline — like the chicken dinner picnics and benefit concerts. The Launfaul Circle, a group of Black women school teachers, were often among the performers. But one of Alpha Home’s biggest gifts came from Madam C.J. Walker, the Black philanthropist and pioneering businesswoman who built an international hair care and cosmetic brand from scratch.

In 1915, before Walker moved her home from Indianapolis to Harlem, New York, it was her “desire to see the entire indebtedness paid on Alpha Home before leaving the city,” The Indianapolis Recorder reported. A year later, in 1916, Walker staged “one of the biggest affairs ever given in Indianapolis,” to fundraise for Goff’s Alpha Home. When Walker died in 1919, the Recorder wrote about the $1,000 gift she left to the home, then an enormous sum. Today, Goff’s legacy of caring for the aged lives on in a modern-day Alpha Home, an 86-bed LTC facility in Indianapolis that continues to serve the city’s Black community.

A decade after Goff opened Alpha House, Eliza Simmons Bryant, a free Black woman in 1896, was moved to do the same in Cleveland after first turning her home into a haven for those who were Black, elderly, and destitute. Bryant later banded together and fundraised with local churches and Black women’s organizations to open the Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People, which she modeled after similar homes for Black people in Boston and Philadelphia.

At 74, Harriet Tubman, the indomitable woman known for providing passage from slavery for those willing to make a bid for freedom, founded the Tubman Home for Aged and Indigent Negroes in 1908, on land she bought adjacent to her home in Auburn, New York, southwest of Syracuse. Tubman always seemed to have more people to care for than she had space. She struggled and relied on the generosity of others to do this work. But in her words, she said it is “…what the Lord meant me to do.”

When Tubman grew ill, the nursing home and sanctuary she founded also became her refuge. She spent her final days there as a patient and died in 1913.

“She doesn’t get enough credit for being a humanitarian,” Ellen Mousin, a volunteer at the Harriet Tubman Museum and Educational Center in Cambridge, Maryland, the general area of Tubman’s birthplace, told National Geographic.

“People, especially in the North, often don’t realize that African Americans were not usually able to go to nursing homes or healthcare facilities” But, Mousin says, Tubman “ … made it possible.”

In Atlanta, nearly 40 years after Tubman established her Home for Aged and Indigent Negroes, Sadie Mays, a Black social worker, community worker, and wife of late Morehouse College president Dr. Benjamin Elijah Mays, led efforts in Atlanta. At the time, LTC services, especially for Black Americans who were sick, homeless, and often neglected, were inadequate or just didn’t exist in the segregated South.

With space for 60 in a former sanitarium, the place Mays named Happy Haven Nursing Home admitted its first residents on March 24,1947. The Georgia home, according to organizers who recorded its history, was considered Atlanta’s first nursing home for Black people, although it admitted anyone, regardless of race. What was once Happy Haven is now The Sadie Mays Health and Rehabilitation Center, a 206-bed skilled nursing home in northwest Atlanta.

On the heels of Happy Haven’s start, the Rev. John Henry Floyd, a Florida pastor and building contractor was breaking ground, eager to build what is considered Sarasota’s first nursing home for Black residents.

The place that Floyd named the Old Folks Aid Home opened in 1960 with more than 30 residents. It represented a decade of prayers, dreams, and the hard work of a union of choir members and other faithful church goers in Sarasota’s Black community who were determined to care for their own.

Over the years, The Old Folks Aid Home was renamed the J.H. Floyd Sunshine Manor and then The J.H. Floyd Sunshine Nursing and Rehabilitation Center. Today, the home that once bore Floyd’s name is now the Crossbreeze Care Center, a101-bed nursing home that was sold to a Miami-based company and changed hands in 2017, according to the city’s archives.

‘There were a lot of us’

In communities across the country, there were others like Floyd, Goff, and Tubman who ventured to do what hadn’t been done and create what was needed to house and care for Black elderly and vulnerable people. These places opened with little resources and struggled a lot to stay afloat. While many were well run, succeeding in doing good for their own — most of the nursing homes have since shuttered and vanished, taking their history with them.

“After slavery, we [Black people] came together to take care of our poor and elderly, usually with support from Black churches and mission organizations,” Nash says. “This was kind of the starting place for our nursing homes. It’s a simple story, and at the same time, it is unique.”

In Nash’s family, Stoddard always had a place. He says providing “service to elders” was what they did. Growing up, “I heard stories about how my great-grandmother would collect and deliver — through her grandchildren — ‘pennies from heaven’ to help Stoddard serve its residents,” recalls Nash, who now operates and manages the Stoddard Baptist Nursing Home, and a handful of other residential and care facilities that serve mostly Black seniors in Washington, D.C., and Maryland.

“In the early 90s, when I first started in the aging profession, there were a lot of us,” says Nash of the once thriving, often struggling, private, Black- operated nursing homes that dotted the country. About 16 of them, from “California, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York and Maryland, D.C., South Carolina and North Carolina,” formed an association of Black-owned and operated nursing homes in the early or mid-1990s,” Nash recalls.

Those members also joined the American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging, the professional group representing nonprofit nursing homes that is now called LeadingAge. Among this group, they were not only small in number, but they also had a different mission.

“We were taking care of African Americans, the poorest of the poor, and the sickest of the sick in our mainly Medicaid facilities,” Nash explains.

While in the company of his Black peers in the field, Nash says he discovered the forgotten history of how these nursing homes got started — and filled a void, sometimes for more than a century before they shut down. Nash attributes the demise to financial “hard times and regulatory issues” that eventually forced most of them out of business.

What the future holds

At 120-years-old, Stoddard Baptist Home, which Nash oversees, is a survivor. Until June 8, 2022, so was the Black-owned and operated Eliza Bryant Village (formerly the Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People).

That is when the Cleveland, Ohio-based nursing home and a community fixture ended a storied history that dated back more than 125 years.

In a sobering 2022 report, the American Health Care Association (AHCA) revealed that some among the nation’s for-profit nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities are at risk of closure. The profile: small, with fewer than 100 beds, highly rated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, operating in urban areas, and mostly serving low-income residents who rely on Medicaid. When those facilities close, the change will threaten the care of “nearly 450,000 nursing home residents” who are at risk of being displaced.

When he was the president and CEO of Eliza Bryant Village, Danny Williams didn’t need AHCA’s report to tell him the end was near for the place that proudly proclaimed it was “the oldest, continually operating, Black-founded, long-term care facility in the United States.”

The financial realities of providing long-term care and mounting staffing shortages made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic, which the AHCA tracked to impending national closures, proved too much for Eliza Bryant Village to weather. But, Williams says, “inadequate reimbursement for care” is what sealed the fate of the 99-bed skilled nursing home.

“Every day for every Medicaid patient” we were losing more than $100 per patient. That’s just not a sustainable business model,” he said of the federal/state reimbursement rates paid to LTC and healthcare providers for giving care. For their part, patients enrolled in the program have to be impoverished to qualify for care. While Medicaid reimbursement rates vary by state, they are always below Medicare’s reimbursement levels, or the fees charged to people who pay for their own care. And for Medicaid homes, the struggle to compete is real.

It’s a funding formula that also fuels racial health disparities in LTC facilities, says University of Central Florida Assistant Prof. Latarsha Chisholm, MSW, Ph.D. whose current research is looking at this issue.

“Statistically, Black people rely on Medicaid more than non-Black people do to pay for nursing home needs, so nursing homes that care for them receive lower reimbursements and therefore have fewer resources to provide quality care to residents,” Chisolm says.

“There is no simple fix … but we need to address it,” argues Chisholm who, with colleagues, is analyzing financial and quality data, including profitability and the costs to operate for nearly 12,000 nursing homes nationwide from 1999 to 2004.

The demise of Eliza Bryant Village, the place that Williams called “a safe haven for Cleveland’s elderly Black population since the 19th century,” is not an isolated case. In Ohio, other nursing homes that have been teetering financially and short staffed since before the pandemic’s punch, will likely suffer the same fate, suggests industry experts like Pete Van Runkle, executive director of the Ohio Health Care Association, which is affiliated with the AHCA and is one of the largest lobbying groups for the senior care industry in the state.

The national forecast for nursing homes is just as bleak. Two-thirds of nursing home administrators, already reeling from COVID-related costs, said their facilities “won’t make it another year,” according to the American Health Care Association/National Center

for Assisted Living, the nation’s largest nursing home trade association.

Promise out of Baltimore

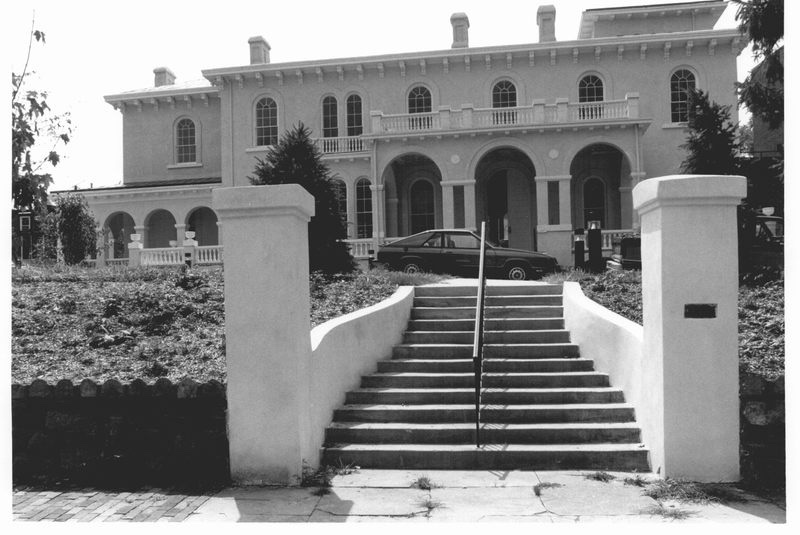

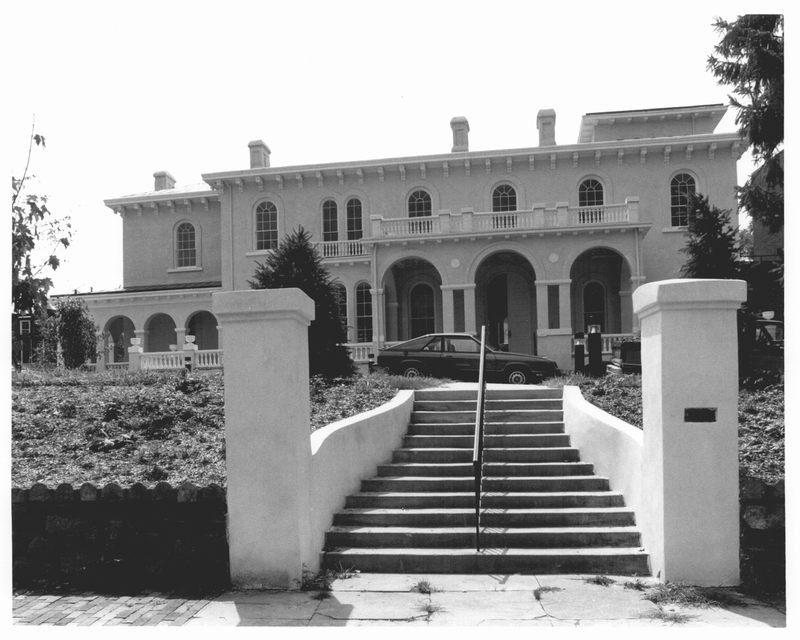

The Rev. Dr. Derrick DeWitt Sr., director and chief financial officer of Maryland’s oldest Black-owned nursing home is determined to buck the downward trend. This year, he says, could finally be the start of realizing the long-held dream he and his executive team have held for expanding the 29-bed Maryland Baptist Aged Home. It also means reimagining long-term care facilities that serve large numbers of Medicaid recipients—at least in Baltimore’s predominantly Black, low-income Westside.

Maryland Baptist Aged Home (formerly the Maryland Baptist Aged Home for Colored People), which serves mostly Black, and Latino residents, is anchored along a busy street in a bleak block made of modest and rundown rowhouses. A sprawling drug rehab center is its neighbor.

DeWitt grew up nearby and pastors the First Mount Calvary Baptist Church in the same Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood, an area he describes as “one of the most economically underserved communities in America.”

More than 10,000 people live in this neighborhood, but there are no grocery stores with fresh produce or meat within a mile. Nearly two years ago, DeWitt, the farmer and businessman, set out to change that when he helped launch Strength to Love II, a 1½-acre urban organic farm that provides neighbors and those returning from prison access to fresh food — and jobs.

The Black preacher who says he learned on the job how to lead a nursing home won national praise, and even garnered global media attention for Maryland Baptist, the only nursing home in the country to have had zero COVID-19 cases throughout the pandemic, according to state records and DeWitt.

Since then, DeWitt says, the financially challenged and once obscure nursing home now has “a waiting list to get in,” since he told the world that those operating the tiny home in “the hood” knew how to protect and care for its seniors.

When the pandemic began in 2020, DeWitt and his team put the small home on lockdown, bought up as much personal protective equipment as he and his staff could get — and got ready to fight. When he came to the job, one of the first decisions DeWitt says he made was to take a pay cut so that he could hire a nurse who was an expert in infectious disease control.

“We were excessive, we were extreme, we were emotional,” DeWitt says.

Activating an infectious disease protocol was a part of the early and aggressive safeguards he put in place. He couldn’t continue to pay the expert nurse, but she delivered what was needed to help residents and staff survive—a plan to contain COVID-19 and any type of infection that was a threat.

“Everything that she [the infectious disease expert and nurse] had in the book, I said, ‘Let’s multiply these times 10 and do it,’ ” DeWitt said of his game plan.

To his small band of employees, DeWitt issued this directive: “Don’t take public transportation, wear masks at home, and limit exposure to your family.” To help ease the transportation burden, they received rideshare subsidies. It was a part of “the extreme measures” DeWitt didn’t hesitate to take if it meant keeping his aunt and the other vulnerable residents inside the one-story nursing home free of COVID.

Nearly three years later, the pandemic has simmered, and the spotlight on the home and its director has dimmed, but DeWitt and his staff remain vigilant against the same COVID-19 threat that he says if unleased, “could wipe us out.”

They also remain focused on the future and change.

DeWitt’s dream of building and acquiring continuing-care retirement homes where more low-income elders can live is in view. His underlying belief is that poor Black and brown Baltimore residents should be able to age and grow old with access to high-quality care and dignity in the communities they already call home.

The United Baptist Missionary Convention owns the Maryland Baptist Aged Home and the huge plot of unused land that is adjacent to it.

“See all of this? We want to transform it,” says DeWitt, arms outstretched.

In the distance, and even across the street, he sees opportunities and imagines a kind of resurrection in a neighborhood where most see decay. Even without a firm financial grip, he is looking beyond the overgrowth and trash that mar the open space. From the sidewalk, DeWitt points to places to house “a new 75-bed long-term care unit, a 50-bed assisted living facility, a 20-bed dialysis center” space for a vegetable garden to sustain residents and employ neighbors, and so much more.

For a growing and aging population of people of color and those who are low-income, this kind of community-centered approach can put needed services and support services within reach, says Robyn Stone, senior vice president of research at LeadingAge, an organization that advocates for nonprofit aging service providers.

“As we talk about the future and quality of care, and services like dialysis, and housing, especially for people of color, the focus needs to be on a community solution, not just a nursing home solution,” adds Stone, who was deputy assistant secretary for disability, aging and long-term care policy and acting assistant secretary for aging with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under President Clinton.

Deke Cateau, the CEO of A.G. Rhodes, one of Atlanta’s oldest non-profit nursing home organizations, says the three homes A.G. Rhodes operates are already on that path.

“I call it bridging community and the resident population,” says Cateau of some of the efforts underway, such as building a core of volunteers and bringing dialysis in-house for his facility’s 1,100 seniors.

“Now they don’t have to leave their home to get treatment. Offering this service is also a way to address health care inequities,” says Cateau, who is Black and aware of the disproportionate number of Black people in Atlanta and elsewhere in the nation who have kidney disease and receive dialysis. For Cateau, offering dialysis and dementia care at A.G. Rhodes also makes good business sense.

“These services help to increase our Medicaid reimbursement rate,” adds Cateau, a veteran in the long-term care industry and one of its few Black leaders. “Of course, we have to meet the bottom line. No margin, no mission,” he said.

In Baltimore, DeWitt, like Cateau and Stoddard’s Steven Nash, is poised for change, even in an uncertain and financially challenging time for the long-term care industry. He’s also determined to care for Black seniors as were Tubman and many other Black people before him more than a century ago.

“For years, no one cared about a poor Black nursing home in a poor Black community. But “looking forward,” says DeWitt, “We want to be the ones to say this is what patient-centered, culturally relevant, and community-based nursing homes should look like in the future.”

This piece was executed with the support of a journalism fellowship from The

Gerontological Society of America, The Journalists Network on Generations, and the

John A. Hartford Foundation.