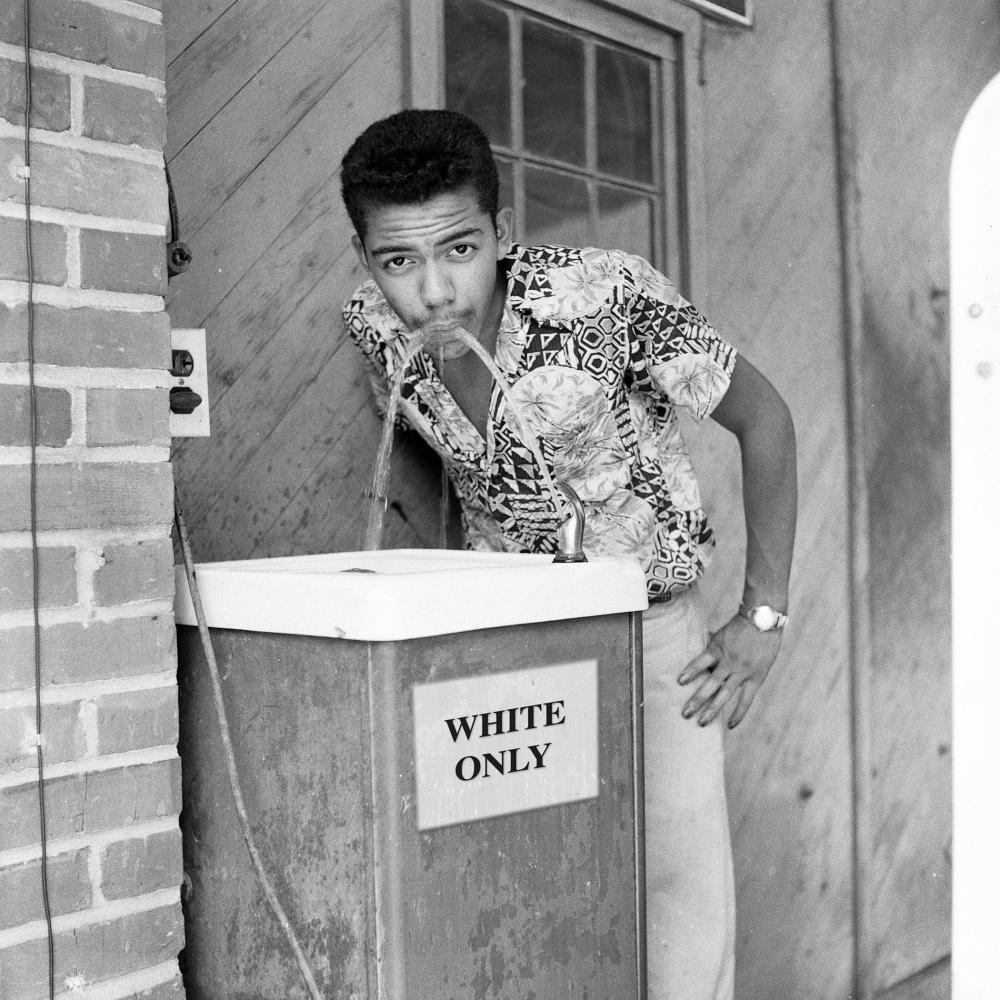

Cecil Williams was grounded for drinking from that water fountain. Three days later, his mother eventually let up.

At 18, thirsty on a hot South Carolina afternoon, he had committed the small act of defiance that would later become one of the most recognizable images of segregation in America.

“It was such an unimportant thing that we did all the time that I didn’t place any emphasis on it,” Williams said. “It was everywhere, restrooms, doctors, offices, there were some signs and symbols like that everywhere”

But the photograph of the young Black boy sipping from a “whites only” fountain became shorthand for an entire era of institutionalized racism.

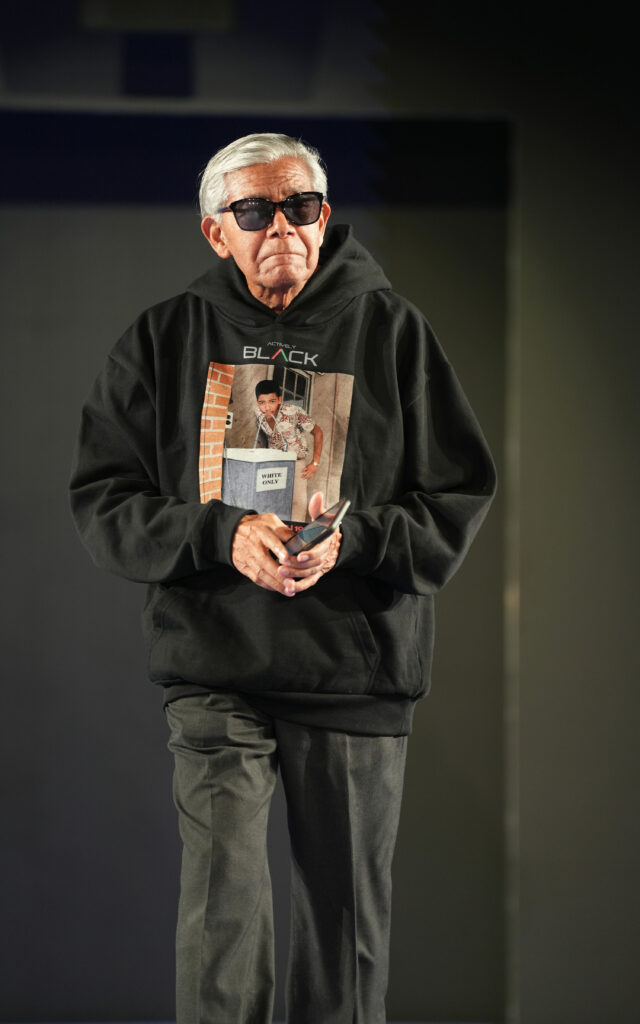

Seventy years later, Williams found himself backstage at Sony Hall in Manhattan’s Times Square, adjusting a hoodie and preparing to walk a New York Fashion Week runway while that historic photograph of him at the water fountain played on screens above him.

The weather in New York was perfect on this Friday night in September, above 80 degrees, clear skies, the kind of evening that made Williams grateful he had made the trip north by train rather than flying.

At 88, he still doesn’t like planes.

His wife Barbara had flown up ahead of him, but Williams preferred the rails, old school and unbothered by the ribbing he took for it.

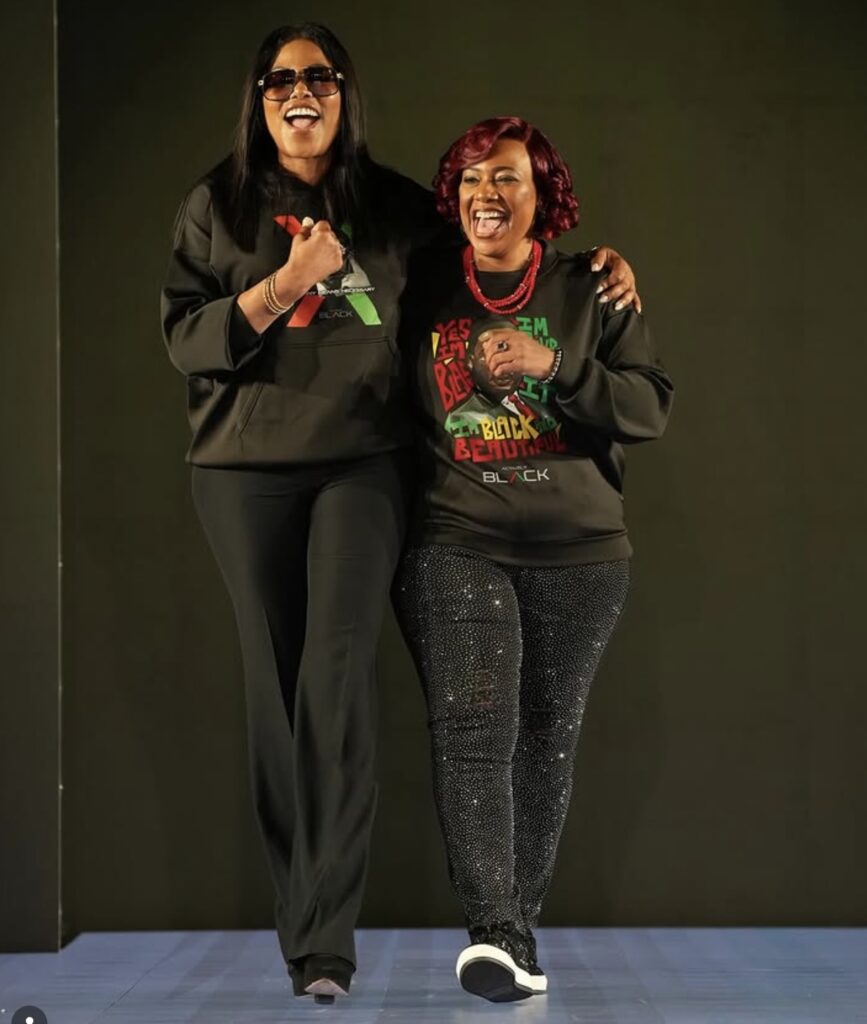

By 9:30 p.m., Sony Hall was packed with nearly 1,000 people squeezed into every available seat. The venue, typically reserved for concerts, had been taken over by Actively Black clothing line founders Lanny Smith and Bianca Winslow and reformed into something they insisted was “not a fashion show.” The phrase was both literal and figurative, with the event using New York Fashion Week’s prominence to pay homage to living history.

Williams sat in the squeezed-in seating the show’s producers had found for him at the last minute, watching as Ruby Bridges prepared to walk ahead of him. Bridges, who had integrated the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans at age s6 now wore an Actively Black hoodie dress, her presence a living reminder of how recent these struggles remain.

“It was just overwhelming … to be in the likes of people like Ruby Bridges and the other greats who I look up to as heroes,” Williams said. “Here we were in New York and in the 25th year of the 21st Century, still talking about the color barrier, that segregation and racism is still alive.”

At 71, Bridges represented the persistence of memory, that the children who broke segregation barriers are not distant historical figures but elders still among us.

“The show lands at a moment when the U.S. is in a struggle over history itself,” Keicia Shanta, a San Antonio-based fashion industry analyst who has worked with major brands and New York Fashion Week, told Black News & Views.

“By placing Ruby Bridges, whose very childhood is being contested in school boards, onto a global runway, Actively Black made a bold counterstatement: you cannot erase us,” Shanta said.

One of the evening’s most powerful moments came when Bernice King and Ilyasah Shabazz took the runway. The daughters of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X walked out separately at first, and then returned to the stage together with Jay-Z’s “Made in America” providing the soundtrack. The two women, whose fathers’ philosophies were often cast as irreconcilable during the height of the civil rights movement, walked in step as the track’s opening notes filled Sony Hall. They embraced at center stage and clasped hands as an offering of a visual reconciliation to the fact that their fathers met and shook hands only once.

The crowd’s response was immediate.

“I feel like I’ve walked away just feeling so inspired,” New York-based activist Tamika Mallory told BET. “Especially for the times that we’re in. When Bernice King came out, I thought I was going to lose it. I cried,” Mallory said.

The show pulsed with cultural celebration. Models jumped rope in formation, performed street dances, and staged a live version of Fast Life Youngstaz’s “Swag Surfin’ ” that turned the formal New York Fashion Week venue into a block party, according to accounts on social media. The family of late artist Jean-Michel Basquiat presented a fashion line inspired by Basquiat’s groundbreaking work, which combined abstract expressionism and graffiti. Performers in sequins and fedoras paid tribute to Michael Jackson. The Harlem Globetrotters were honored on their centennial anniversary.

For Williams, the surreal quality of the evening, as he recalled it, where small-town South Carolina met big-city glamour, lingered. His wife had given him sunglasses to wear on stage. A friend suggested he take pictures of the audience as he walked, though Williams admits he was mostly faking it, holding his camera without actually shooting.

Before taking the stage, he had been instructed to pull his hoodie up when he reached the end of the runway, a detail that nearly slipped his mind until the last moment.

Williams made sure not to overstay his moment.

The path to that runway had begun six months earlier when designer Smith and his team traveled to Williams’ museum in Orangeburg, South Carolina, to secure a license for the water fountain photograph. Williams appreciated that they asked because too many times over the years, the image was stolen from him and his copyright violated. But Smith and Actively Black seemed legitimate, and within a month of putting the photograph on T-shirts, they had sold $50,000 worth and paid Williams the promised $5,000 commission.

When Smith called asking him to participate in the New York Fashion Week show, Williams and his wife agreed immediately. The photographer who had spent decades memorializing history from behind the camera would step in front of it, his own image projected above as he walked.

The evening was heavy with meaning. Videos were played throughout the show displaying sit-ins, marches and the broader sweep of the civil rights struggle. Williams’ presence served dual purposes, one as the young person in the photograph and the other as the man who later documented the 1968 Orangeburg Massacre, when police fatally shot three students and wounded 28 more on the campus of HBCU South Carolina State University.

He had photographed many of those students. He had known them personally and is disappointed that their legacies and sacrifices seem to have been forgotten.

Hassie Benjamin Haith Jr., designer of the Juneteenth flag, jogged onto the stage as Beyoncé’s “Freedom” filled the hall, pressing his hands together in prayer before opening his arms to embrace the crowd’s cheers.

“Juneteenth is a blessing that came from our ancestors. I believe it’s with us today because it wants this country to change and be more humane,” Haith told BET after the show.

The show concluded with an unexpected personal moment. Smith gave an emotional speech about the effort required to create and organize the show when Winslow, his cofounder and partner, emerged from backstage, revealing her pregnancy, according to video shared on social media.

“If you knew what it took to make tonight happen, you would know why I can’t take no credit for it. God is so good, y’all,” said Smith, holding back tears.

The couple also shared that they will be having a son who is due in December.

For Williams, the evening represented both reclamation and warning. The racism he experienced as a teenager—overt, visible, sanctioned by governments at every level—has evolved today into something more subdued but equally persistent.

“Those days, it was overt and out in the open and very visible everywhere,” Williams said. “Now it’s subdued and hidden, and it happens everywhere. … It happens at the golf courses. It happens in the opportunities that are lost to African-American citizens.”

Williams recalled that the young people at the New York Fashion Week event seemed pleased to encounter figures from history and social media. But he that people like Ruby Bridges and the other civil rights veterans need to surface again to remind a new generation that the fights their predecessors won are not permanently settled.

The photograph that got Williams grounded for over two days has become an icon of resistance. Back then, drinking from segregated fountains was commonplace, so unremarkable that he didn’t even file the story with Jet magazine, where he was working as their youngest correspondent.

That ordinariness made the defiance more profound. A thirsty teenager willing to risk consequences for a drink of water became a symbol of the small daily acts that eventually toppled over an entire system of oppression.

At 88, still building a museum in Orangeburg that hopes to draw 200,000 visitors annually, he embodies the ongoing nature of historical work, that some fights must be fought across time.

“I think Tom Brokaw was wrong about his generation being the greatest. I believe that our generation is the greatest generation, because as first-class citizens, we fought a larger enemy,” Williams said. “It took us 400 years and still the open ended question remains: ‘ “When is racism going to stop?’ ”