Total solar eclipses like Monday’s occur only when the moon is close enough to the earth to completely cover the sun. During a total eclipse the world barrels into darkness, and the onrushing shadow reminds us that we are mortals alive on a swiftly moving planet. For the first time, we can see the sun’s corona. We can see that the sun is a living fire, with spouts and tails that snap at its edges.

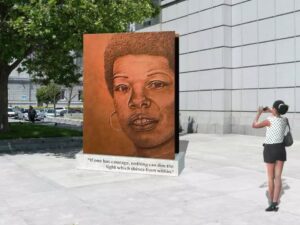

No wonder total eclipses have sparked fear and awe in the minds of our ancestors and have caused humans throughout time to wonder about our place in the universe. As we prepare for Monday’s total solar eclipse, I am thinking of my ancestor, Benjamin Banneker — the Black scientist, mathematician, surveyor, and astronomer who lived during the Revolutionary era and whose life was changed by his prediction of an eclipse.

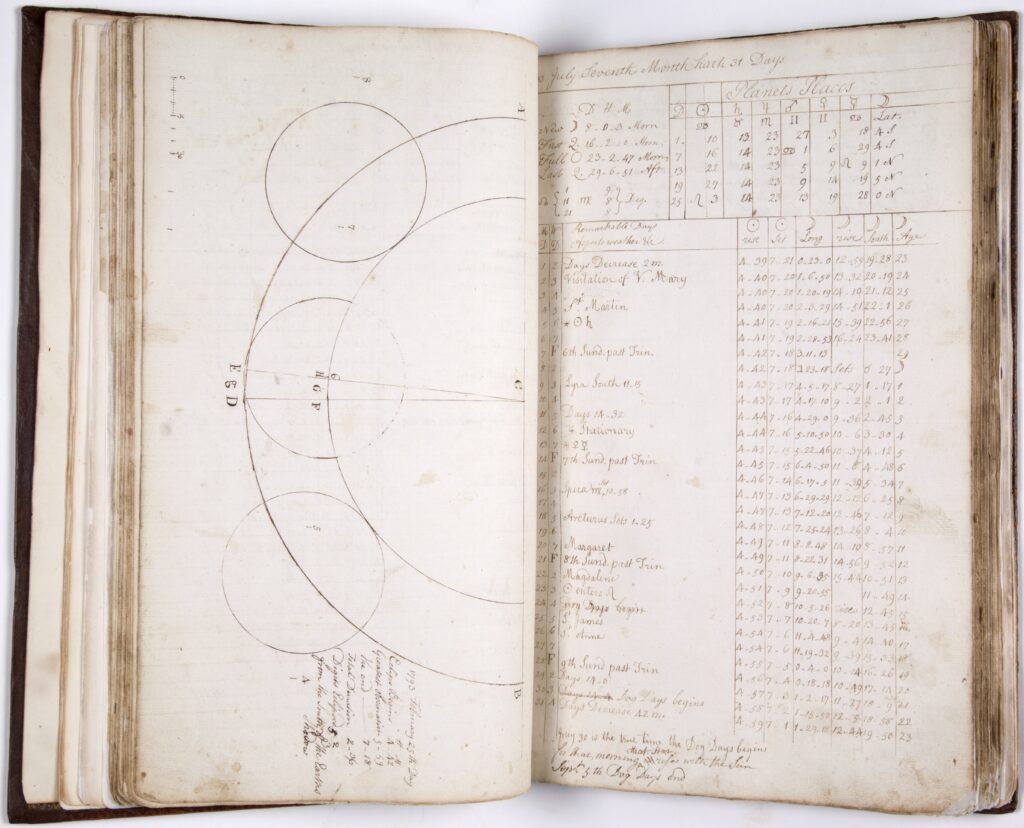

Benjamin Banneker was born in 1731 in Baltimore County, Maryland, to parents who had survived both enslavement and indenture. When Benjamin was 6-years-old, his father Robert purchased 100 acres of land, putting the deed in both his and in Benjamin’s name, in hopes of securing freedom for the next generation. From the time Benjamin was a child, he loved to learn. He read avidly, built a working clock, taught himself higher mathematics, and made astute naturalistic observations in his manuscript journal.

In his writing, Benjamin correctly noted the fact that the Star of Sirius is actually two astronomical bodies rotating around each other, a “discovery” credited to a European scientist decades later. But the Dogon people of Africa had known about the double nature of the Star of Sirius long before, and Benjamin had been influenced by his father’s complex African cosmology.

By the time of the total solar eclipse of 1789, Benjamin Banneker was 58-years-old, and already well-known as a local intellectual, scientist, and inventor. Benjamin’s friend George Ellicott had lent him a telescope and several textbooks on astronomy, and Benjamin had become obsessed with observing the stars and doing astronomical mathematics. Benjamin wrote George a letter to share his projections for the 1789 eclipse, and to note an inconsistency in the two leading textbooks. Then he concluded the letter, saying, “if I can overcome this difficulty,” I would not doubt my ability to “Calculate a Common Almanack.”

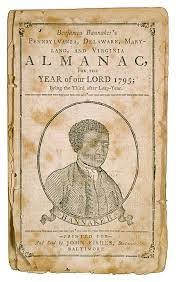

It was the first time Benjamin had declared such an ambition, and he thrilled a bit at the challenge. An almanac was as important back then as a smart phone is today. Some wealthier households had a Bible, but many more homes had an almanac. Almanacs contained holidays, court dates, currency exchanges, directions between cities, inspiring quotes and poems, as well as an astronomical ephemeris which listed tide tables, sunrises, sunsets, moon phases, equinoxes, and eclipses. Almanacs helped farmers to determine the best time to plant their crops, and helped sailors to safely cast into the tides. Almanacs were central to 18th century life, and Benjamin knew that if he could publish one, he could be seen as the Black intellectual and full American citizen that he knew himself to be.

As we prepare for Monday’s total solar eclipse, I am thinking of my ancestor, Benjamin Banneker — the Black scientist, mathematician, surveyor, and astronomer who lived during the Revolutionary era and whose life was changed by his prediction of an eclipse.

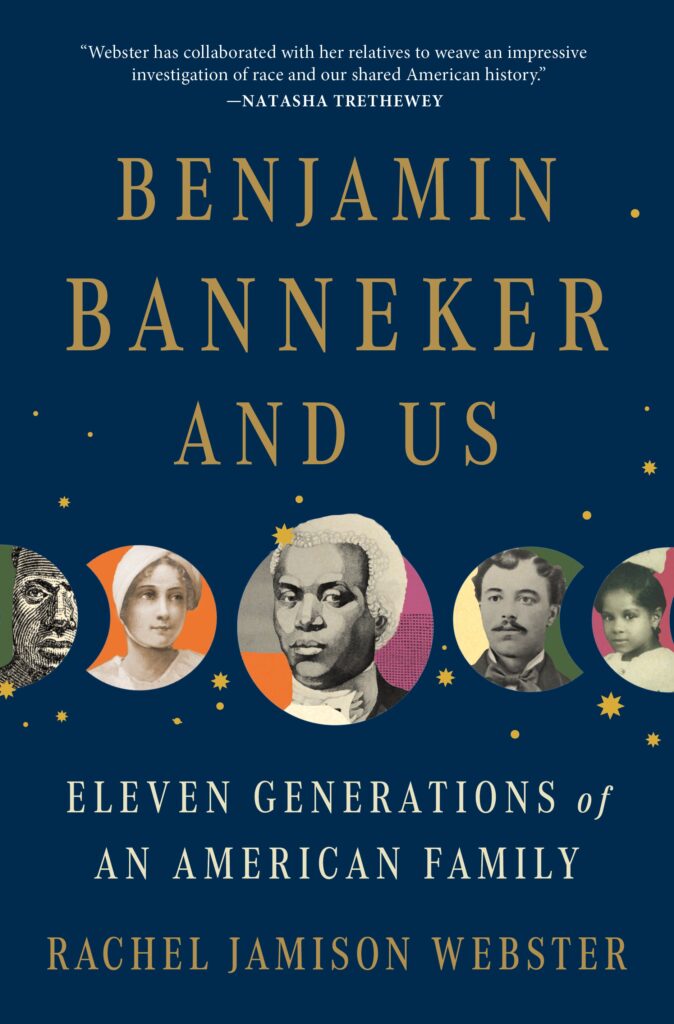

Rachel Jamison Webster

So while many feared the total solar eclipse of 1789, Banneker studied it, predicted it, and ultimately took it as a sign that he too could take his place in history. Months later, he sent out his almanac for publication, defending the accuracy of his astronomical computations and noting, “I suppose it to be the first attempt of the kind that ever was made in America by a person of my Complexion.”

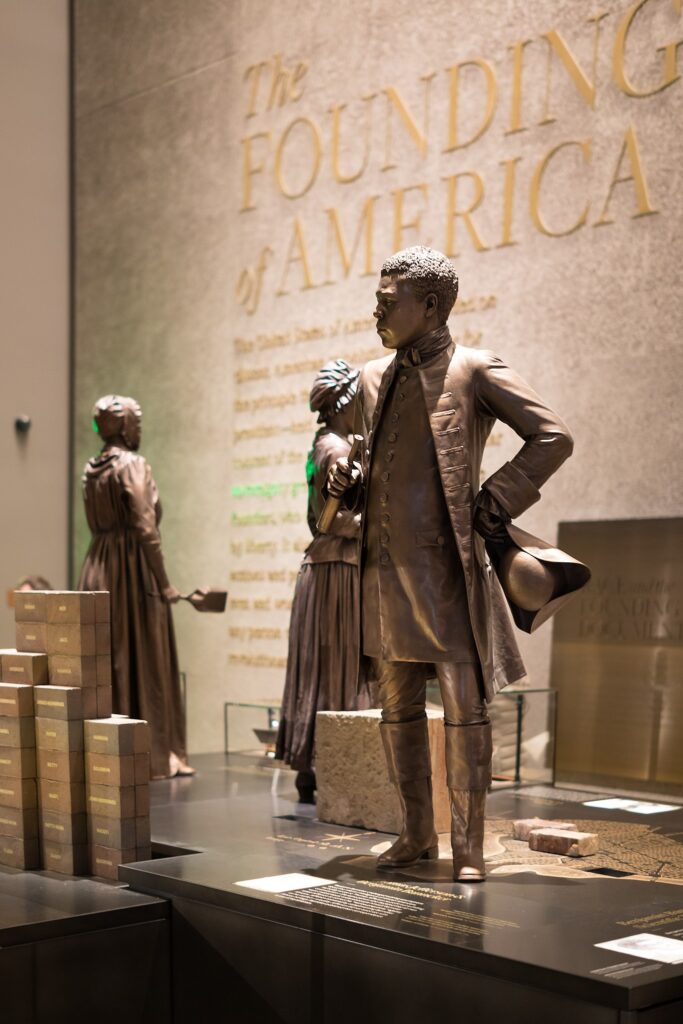

The publishers, however, did not quite believe Banneker’s genius, and they delayed so long in the almanac’s acceptance that it became too late to publish it. But Benjamin had also shared his almanac with Major Andrew Ellicott, who was the most prominent surveyor of the era. Andrew Ellicott was impressed by Benjamin’s mathematical accuracy. He asked George Washington and Thomas Jefferson if he could hire Banneker as his assistant to survey the new country’s capital of Washington, D.C. The founding fathers signed off on the hiring, and Benjamin Banneker became the first Black American to be paid by a federal commission.

Benjamin’s work on the survey involved staying up all night, looking through a giant telescope, and doing the astronomical computations to plot out the capital city’s streets and buildings. After he returned home, Benjamin compiled and published a new almanac for the year of 1792. This almanac became an instant bestseller and proof of Black American intelligence.

Benjamin’s next almanac of 1793 included his famous letter to Thomas Jefferson, in which he spoke out vehemently against slavery, and Jefferson’s reply, in which he said that he hoped to see more examples of Black achievement. This almanac was passed around as evidence of Jefferson’s hypocrisy and became one of the most important publications of its time. Benjamin continued to publish bestselling almanacs every year until 1797, and to do accurate astronomy until his death in 1806.

When we see something vast and mysterious like a total solar eclipse, we can feel fear or wonder. Benjamin Banneker was one of our country’s great geniuses, and his genius stemmed from his courage to be curious, his stamina to keep learning, and his wisdom to let his wonder and intellect lead the way. I can imagine him today, awaiting this next eclipse with excitement.

Rachel Jamison Webster, a descendant of Black astronomer and mathemetician Benjamin Banneker, is a professor of creative writing at Northwestern University and the author of “Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of An American Family.”