Kevin Leary’s story is one of hope amid the 9/11 heartbreak. He survived a most horrific scene to come out on the other side with a life that helps him.

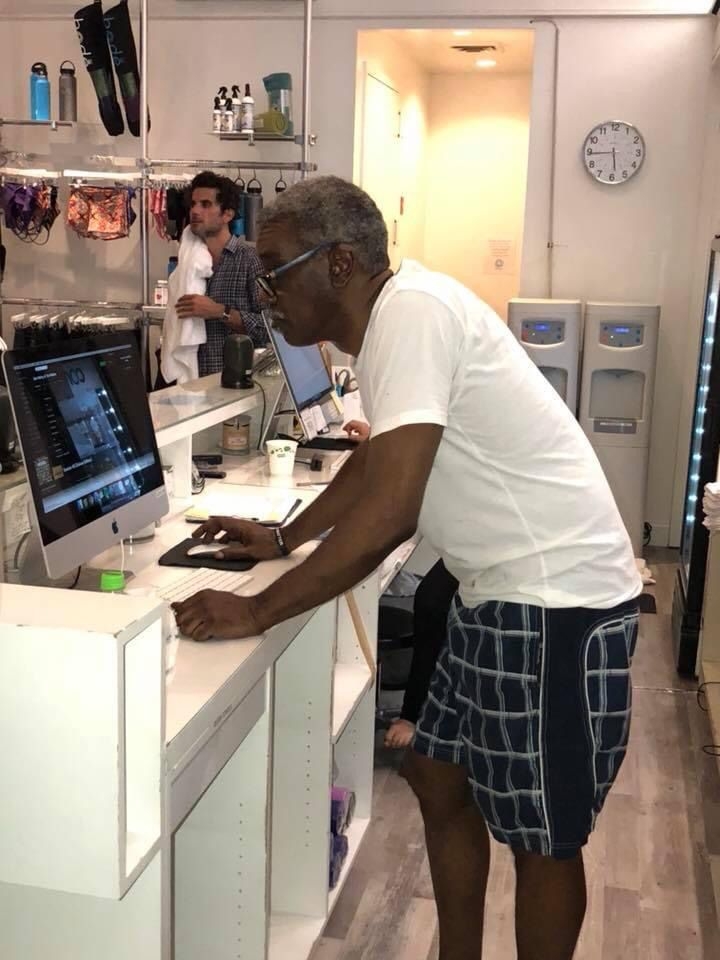

Today, Leary, 62, of Manhattan, is a yoga studio manager (on hiatus because of the pandemic) and pondering a move to Connecticut with his daughter and granddaughter. He keeps in close touch with other survivors.

Once upon a time, Leary was a veteran chef working out of the World Trade Center, preparing the finest foods for banquets and restaurant guests.On Sept. 11, 2001, he was organizing pasta in a walk-in refrigerator at the Marriott-owned restaurant where he worked. He felt a small rumble that he shook off. When he exited the refrigerator, he was surprised to find the restaurant empty. That’s where his life took a drastic turn.His story is part of National Geographic’s documentary series “911: One Day in America.”

It made sense that Leary would become a chef. His father ran successful restaurants in Harlem and the Bronx in the 1970s. Leary started cooking when he was 10 and began working for restaurants at the towers in 1979. By 2001, Leary was a production chef who made menus and dish specials for four restaurants in the towers. He lived in the small city of West New York, N.J., and would look across the Hudson River at the towers each morning before work. The morning of Sept. 11, 2001, was clear, he remembered.

At work that day, Leary finished his task in the refrigerator and walked out into the now-empty restaurant. One lone diner who remained advised Leary to look into the adjacent courtyard. Leary had a hard time pushing the door open. When he succeeded, he saw that the door was blocked by a severed arm.

Leary walked into a carpet of arms, legs, heads and luggage. The bodies of people jumping from the North Tower slammed through the glass ceiling of the courtyard.

“It just wasn’t quite registering,” he said. “I can’t believe what I’m seeing and then a body falls out of the sky and lands right in front of me … and broke up.”

Leary joined up with the diner and a colleague/friend. He walked toward the elevator but the other two were wary of it and decided to find another way out. Leary would later learn his colleague/friend did not survive.

“After I saw the bodies, everything just went in slow motion,” he said. “I never had that feeling.”

At the employee level two stories underground, Leary saw people eating, oblivious to what was unfolding outside. He warned them to leave but they didn’t understand the urgency, some even grabbing coffee to go, Leary said.

Outside he saw burning bodies and a woman running around, her skin burned off. A man with blankets tried to cover and put out the fire on people who were burning.

Leary looked up and saw the gaping hole in the North Tower.

“I hadn’t smoked a cigarette for two years _ I went to the store to get cigarettes,” he said. “The next plane flew right over my head. The rumbling you could feel inside of your body. … It looked like a missile. You could feel the heat of the fireball and everyone just ran.”

Streets in Lower Manhattan, the original part of the city, are narrow and close to one another. Leary covered the equivalent of three or four regular city blocks when he and everyone else felt something.

“The ground is literally shaking and somebody said the tower is coming down,” Leary said. “A cloud of soot comes around the corner. I ran and climbed a tree.”

The soot was filled with what seemed like pebbles and he and others pulled it out of their mouths and brushed their faces. Some were throwing up. A crowd of people on the FDR Drive above Leary helped him from the tree up onto the road.

“On one side of the highway, pedestrians were walking north and on the other side, emergency vehicles were going south,” he said.

He felt lonely and was happy to come across a fellow employee from the Marriott hotel at the World Trade Center. They hugged and walked together. Leary made his way north to 42nd Street and then west to the Hudson River. Ferries were taking people over to New Jersey and Leary was welcomed onto a boat.

Leary’s mother and sister, who also lived in New Jersey, had prepared a big meal for him after his ordeal but he just wanted to go home. For months, charities helped pay his bills while he slipped into a deep depression. The only time he turned on the lights was when his daughter, who was in high school, came to visit.

“My daughter said something’s not right,” Leary recalled.

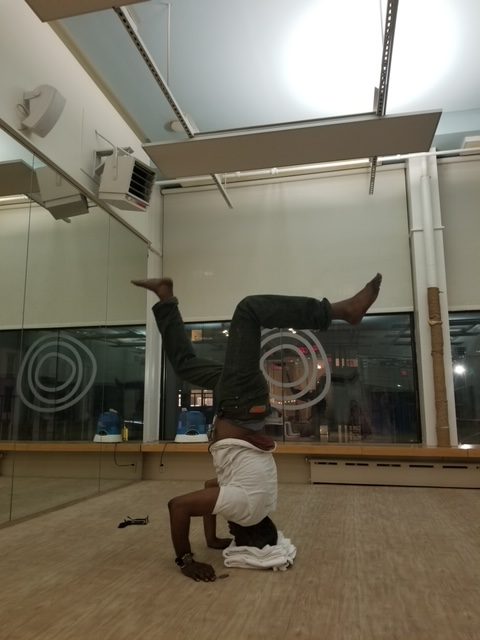

His sister taught yoga and introduced him to the practice. That began to pull all of his pain out of him. Sometimes he would cry during a session. Bikram yoga, which is practiced in a very hot room, is the type of yoga that he prefers. He’s introduced his friends to it.

Leary’s love for yoga grew so much that he made it his livelihood, managing a series of yoga studios in Manhattan. At the time of the pandemic, he was running a studio on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. He is collecting unemployment benefits since coronavirus forced the studio to close, but he is still optimistic about life. He is looking to buy a home in Connecticut with his daughter and granddaughter.

He is coping, he said, even with the lingering pictures in his mind from that day.

“Every August I relive it,” Leary said. “This time of year is really difficult.”