He pulled up to the rally on an early autumn afternoon in 1967, when there was unrest in the streets and revolution in the air. Conspicuous as he strode through a gathering of Vietnam War protesters in West Oakland’s DeFremery Park, Harry Edwards had a strong sense of foreboding.

A bit later, as the 24-year-old Edwards stood in the crowd with Black Panther Party co-founder and fellow civil rights activist Huey Newton, a student organizer ended his remarks by intoning into the microphone, “Don’t trust anybody over 30!”

Edwards looked at Newton, and the two burst out laughing.

“Hell, Huey, I hope I live to be 30 to be distrusted,” Edwards said, projecting the understandable fatalism of their shared circumstances.

He wasn’t being melodramatic. Within a few weeks Newton would be jailed and charged with murder after having been wounded in a shootout with police officers, adding to a growing toll of violent tragedies involving pillars of the civil rights movement.

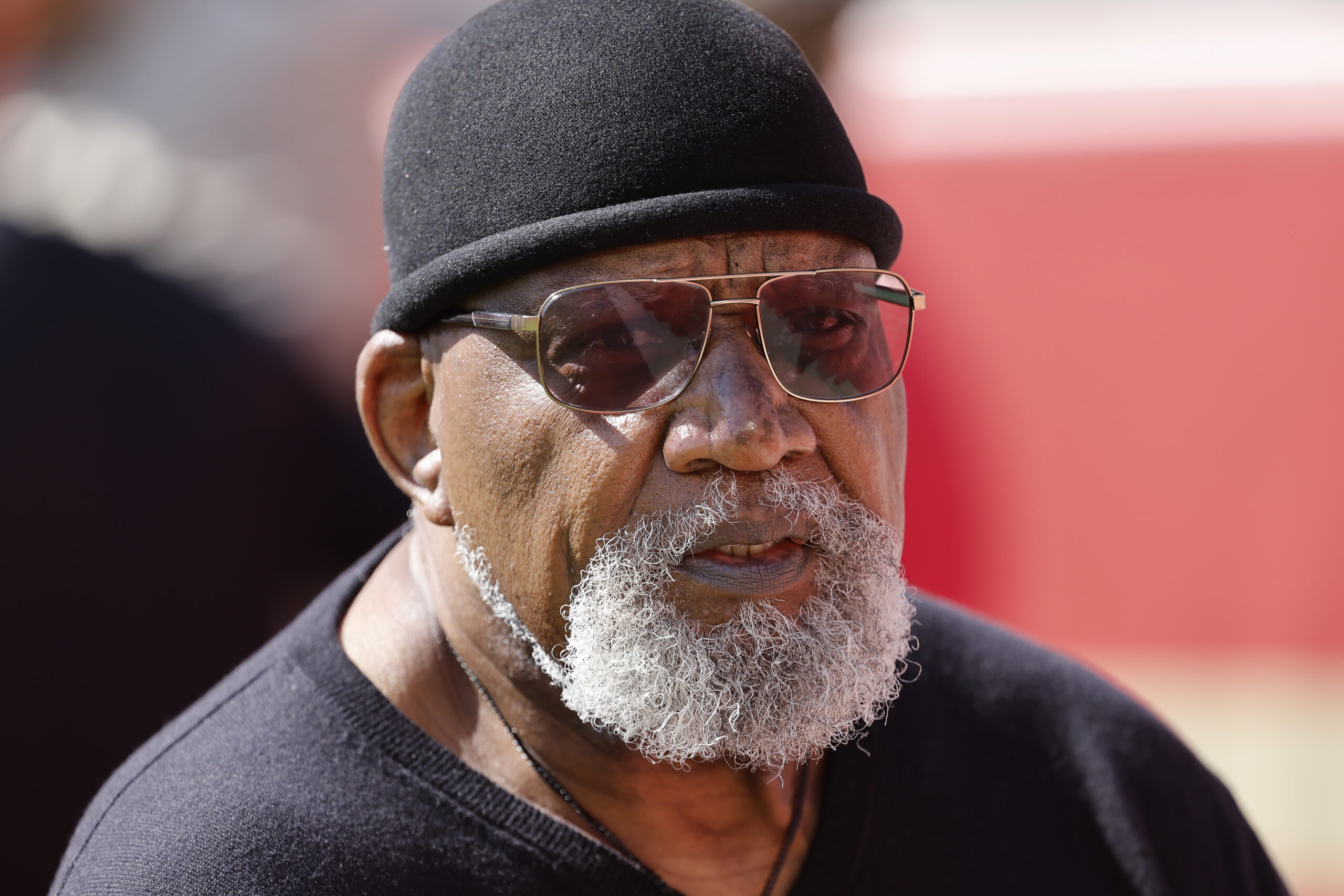

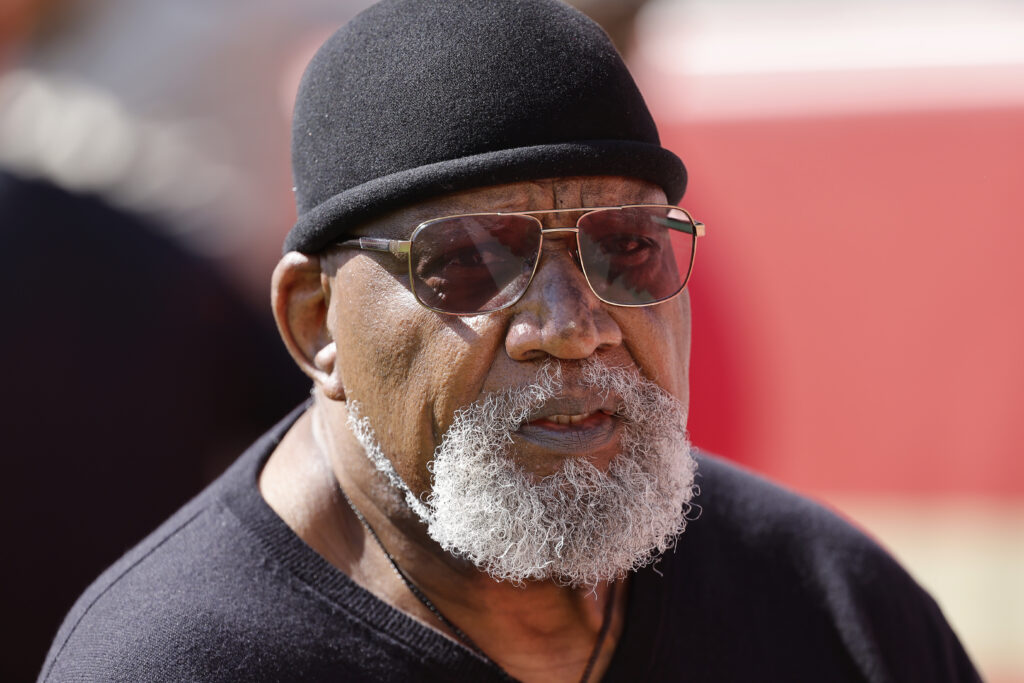

More than 5½ decades later, to his amazement, the 6-foot-8 Edwards is still standing tall. At 80, the esteemed Bay Area sports sociologist and activist has spent an entire lifetime cheating death. But now, not for much longer.

“This is just about the end of the line for me,” said Edwards, who is suffering from terminal bone cancer. “It’s not a morbid or fearful situation. We have an obligation to show those coming after that this inevitable phase of life can be handled with courage, dignity, grace and even a modicum of humor.”

During our nearly three-hour conversation last month in a Levi’s Stadium office, Edwards, a San Francisco 49ers consultant since Bill Walsh’s heyday in the mid-1980s, displayed those attributes — and sprinkled in more than a modicum of comic relief.

About his decision not to receive treatment for his condition, at least at this time, Edwards smiled and said, “At some point, I’m not being made comfortable; I’m being kept fresh … propped up in a corner someplace with a 1,000-yard stare and a line of drool on my chin from a smile that looks like a mortician put it there, and only a surgeon can remove. And people (would) say, ‘That used to be Dr. Edwards.’ ”

If Edwards exudes a serene sense of acceptance as he awaits the end of a life well lived, he has his reasons. The man has left a major imprint: crafting an Olympic protest that remains indelible and iconic; essentially creating an enduring academic discipline; and fighting for social justice alongside figures such as Malcolm X, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Maya Angelou. His impact on the sports world has been seismic, especially in the Bay Area, where Walsh, Dusty Baker and Colin Kaepernick are among the many people whose actions he has influenced.

He’s also calmed by the conviction that there’s no sense in being scared of what’s coming. Edwards stopped fearing death long ago.

The prospect of a brutal and sudden demise was always a thing, in the 1960s and beyond. When Sandra Boze, his wife of 54 years, first brought Edwards home in 1968, he recalled with amusement, “her father’s initial response to me was not encouraging.”

By then, having called for Black athletes to boycott that summer’s Olympics in Mexico City, Edwards’ reputation preceded him. As he greeted his militant guest in the living room of his Los Angeles home, the dubious dad got right to the point.

“Harry,” he said, “do not get my daughter killed.”

The concern was valid. Once San Jose State sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos carried out their black-gloved salutes on the medal stand in Mexico City, the eloquent radical behind the protest became a man of international ill repute. He stopped counting the death threats at about 300; in one of many harrowing moments, he was once was trailed by a knife-wielding man at a rally in Madison Square Garden. He was under constant FBI surveillance, deemed by director J. Edgar Hoover to be anti-American and a threat to the country.

Given the tumultuous era — and his status as a loud, brash, brilliant advocate for Black empowerment and societal upheaval — he figured his death was only a matter of time.

“Once you determined — after Malcolm had been murdered, after Dr. King had been murdered, after bombs had been thrown in churches, after Medgar Evers had been murdered, after people had been beaten and lynched and shot — that you’re not going to make it, there’s a level of, I don’t want to say freedom, but there’s a level of latitude that transpires,” Edwards said. “Where before you arrived at that point you would have said, ‘Well, maybe I shouldn’t do that, because that’s some dangerous s—.’

“Instead, you say, ‘To hell with that. What’s important is the struggle. What’s important is the message. What’s important is that this be said, this be done. What’s important is that silence and a lack of involvement are evil’s greatest allies. So to hell with that — I’m going to do this, even though I know that it could end badly for me.’ ”

At the time, Edwards took comfort in the words of fellow activist H. Rap Brown, who told him, “You know, individuals never survive. Only the struggle and the people survive.” That point was confirmed, Edwards said, when he attended a rally at which Brown, standing on the dais, was shot and wounded.

Decades later, he’d get a dose of perspective from another Brown: Jim, the Hall of Fame running back and longtime crusader for racial and economic justice. Old friends, they reconnected at a 2014 event, also featuring NBA legend Bill Russell, that commemorated the 50th anniversary of the civil rights movement at the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, Texas.

On the bus ride back to the hotel, Brown told former Black Panther Edwards, “Harry, back in 1967 or ’68 they had me pegged as the meanest, baddest Black man in the country. I’m gonna tell you something: We were scared of you guys! You and Rap and Stokely (Carmichael) and Huey were so far out, you guys were right in (the) man’s face, and you were out there not just domestically but internationally. We were scared of you because we figured you either had to be the most fearless people in this country, or you had to be insane.”

“Jim,” Edwards recalls replying with a grin, “I think we were probably a little bit of both.”

It’s fitting, given that Edwards’ rise to prominence was equal parts crazy and audacious. His was an American success story that had no road map.

After growing up poor in East St. Louis, Edwards came to San Jose State via Fresno City College, earning a track and field scholarship (he set a school record in the discus) and becoming captain of the basketball team. He began to notice the inequities of the NCAA’s amateur-based model on his first Thanksgiving break, when he and some other financially disadvantaged Black athletes, stranded without university housing, spent their nights holed up in a 24-hour donut shop.

“We showed up at the practice after the holidays 10 to 15 pounds lighter, while our teammates had put on weight,” Edwards recalled. “I remember my basketball coach, a great guy named Stu Inman, comment after he’d heard a couple of Black athletes and I had gone fishing on Thanksgiving Day: ‘Man, you guys must really like to fish.’

“My response was, ‘No! We like to eat!’ ”

By 1966, Edwards was standing before a panel of esteemed academics at Cornell University, explaining his plan to study the sociology of sport and make it the focus of his master’s thesis. As he tried to get them “to understand that sports is not the toy department of human affairs,” they practically mocked him, he said.

“They said, ‘There’s no such thing — that’s P.E.,’” he remembers. “For them to sit there and smirk out of pure arrogance and narrow-mindedness, with a nose-in-the-air disposition …”

Edwards persisted, arguing that if dyads and triads, groups of just two and three people, were worthy of study, then 100 million people watching a game should be too. He told the committee, “Not only am I going to do the sociology, but I’m going to prove to you that it has value.”

He didn’t waste much time, founding the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which led to Smith and Carlos raising their fists after earning Olympic medals in the 200-meter dash. After receiving his doctorate at Cornell in 1970, Edwards was hired as a UC Berkeley professor and has resided in the East Bay ever since.

Upon joining the 49ers in 1985 he became extremely close to Walsh, with whom he established a series of progressive initiatives. Together they formed the Diversity Coaching Fellowship, an internship program for minority coaches that still thrives on an NFL-wide level. Its graduates include Steelers coach Mike Tomlin and numerous former NFL head coaches, including current 49ers assistant head coach Anthony Lynn and Rams defensive coordinator Raheem Morris. Edwards, who eulogized Walsh at his 2007 funeral, also joined the Hall of Fame coach in establishing programs — modeled on Black Panther community platforms — that focused on providing players with financial, educational and counseling resources after their careers were done.

In 1987, Major League Baseball hired Edwards to address racial inequities after longtime Dodgers executive Al Campanis proclaimed on national television that Blacks “may not have some of the necessities” to be managers or GMs. Campanis, fired by the Dodgers, was quickly enlisted by Edwards as a consultant — news Edwards first revealed to me, then a student at Cal, during an interview for the Daily Californian. Together, Edwards and Campanis pushed for the Giants to hire Baker, a former star for the rival Dodgers, as their first-base coach. Five years later, Baker became the Giants’ manager, beginning a long, illustrious career that has included three World Series appearances and a championship with the Astros last fall.

Edwards has been a champion for women’s rights throughout his career, consistently drawing attention to the contributions of female activists in the sports world. He had an obvious kinship with Kaepernick, whose anthem protests as the 49ers’ quarterback in 2016, spurred by instances of police killings of Black people, galvanized people across the globe. Yet Edwards is careful to point out that nearly two years earlier, Knox College women’s basketball player Ariyana Smith lay on the floor for 4½ minutes before a game in Clayton, Mo., to protest the killing of Michael Brown in nearby Ferguson.

Similarly, Edwards notes that the pioneer of anthem protesters was U.S. track star Eroseanna “Rose” Robinson, who remained seated when “The Star-Spangled Banner” was played before the 1959 Pan-American Games in Chicago. Edwards said: “She sat on an ice cooler and said, ‘I am not going to stand for the anthem in protest of segregation, discrimination, lynching and so forth of Black people in America. This is not the land of the free if you are Black.’ ”

Drawing attention to lesser-known acts of civil disobedience such as Robinson’s are deeply important to Edwards, who wants to leave behind a record that can provide context for future generations.

He has completed one project, “The Last Lectures,” a 12-part video series in which he traces the history of sports activism from the aftermath of the Civil War (when a Black man named Octavius Catto tried to desegregate baseball) to the empowerment of NBA stars dictating terms of engagement during the 2020 pandemic’s “bubble” playoffs. He’s working intently to finish a six-part documentary series, “The Struggle and the Power,” that covers similarly compelling ground.

And though it may belie the fate he’s now facing, he’s also thinking hard about the future. Long ago, Edwards established that the sociology of sport had predictive value, consistently relying on empirical analysis from his field to make seemingly bold public proclamations (such as the USSR’s intention to boycott the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles) that came true.

He’s troubled by much of what he sees coming now, especially on the collegiate sports landscape. Conference realignment, lack of responsiveness to the proliferation of gambling, the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision and the ongoing assault on reproductive rights at the state level signal potential crises, he believes.

“Dobbs is an existential threat to the continued status, strength and so forth of women’s sports in America,” Edwards cautioned. “Not just in terms of women who are now active, because they may be able to go to another state. But the impact on the pool, that is where the real damage is done.

“You may have the appearance of a sustainable, active women’s sports institution for two, three, four, five years, but the reality is that when you have an entire population that encompasses the women’s athletes pool re-consigned to reproductive bondage … eventually that pool begins to shrink, to the point where a national women’s sports institution becomes unsustainable.

“And, of course, (women athletes) are a prism through which to get a valid view of what is happening in society.”

That tenet — that “sports recapitulate society” — is one of many I learned as a student of Edwards at Cal in the mid-1980s. His teachings, which ultimately extended to my senior honors thesis focusing on racism in the sports media, were invaluable then, and they’ve resonated deeply in the decades that followed and informed many of my journalistic choices.

It feels like we need him now more than ever. To know that he’s in physical pain, and that his time is short, is a crushing blow. And yet, he’s still teaching me and others; in this case, given the improbability of his journey, that we should follow his lead and let gratitude overcome sadness and regret.

It could have ended long ago, and Edwards was prepared for it. In 1968 he joined other activists in attempting to shut down the New York Athletic Club’s annual indoor track meet at Madison Square Garden, in protest of the club’s discriminatory membership practices. A man with a knife approached him from behind when, he recalls, “these three Black guys got out of a car and jumped the guy and said, ‘Man, you better get in the car and get out of here because you’re not safe.’ ”

Edwards soon discovered that his three rescuers — “three Black guys, big Afros, dashikis on, it looked like they could have been part of the rally” — were FBI agents. When they dropped him back at his hotel, he found the ransacked belongings of his suitcase strewn on the bed, minus a brand new, custom-ordered size 16 shoe that had been confiscated. “They took one shoe, he recalled, laughing, “to show you how low they were. I just left the other one on the bed.”

Less amusing to Edwards were the contents of the FBI’s declassified files on him that he’s been poring over in recent years, with many disturbing revelations.

“It’s scary when I look at two things,” Edwards says. “One thing is the roles of so many people that I worked with — statements from coaches, colleagues that were talking to the FBI, students in my classes, (people) really close to you. The other thing is stuff that I knew that I only told one person — (some of it) made up to see what the repercussions would be — that shows up in the file. To find out that person was talking to the FBI on a regular basis? I found that to be unsettling.”

Yet Edwards, who plans to donate the files to the San Jose State library, has been redacting those names, not wishing to trouble those still alive or tarnish the memories of the deceased. It makes sense, given how much he is thinking about his own legacy, and how unwilling he remains to tie the ongoing fight for human rights to any specific person or act or time.

“The one thing that I have learned over the years is there will always be a next phase of the movement,” Edwards said. “There will always be a next phase of the struggle. Why? Because I don’t care how many leaders you kill. I don’t care how old the leaders get. It is not the leaders that generate the struggle. It’s the conditions that generate the struggle. And the conditions persist. There are no final victories.”

This mirrors an Edwards quote displayed above the entryway to the Sports Hall at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. It’s another reminder that for a poor kid from East St. Louis, a college athlete who had to fish for his Thanksgiving dinner, and a Cornell master’s candidate who nearly got laughed out of the room, he has made quite a lasting impression.

“Nobody’s laughing now,” Edwards said.

Yet as his time winds down, there’s also this: His staunch insistence that even as he aims to face “these closing days” with grace and courage — “my bones are becoming chalk,” Edwards said, somewhat dispassionately — nobody should be crying.

We owe it to the man to trust him on this, even if he’s long past the likely fate he mused about at DeFremery Park all those years ago. The end may be near, but Edwards has been at peace with that notion for a long, long time.

“I didn’t expect to live to be 30,” he said. “The thing I hope, after all is said and done, is that people will look at the life and the body of work. At the end of the day, I’m good with it.”