As a baseball fan, sports historian, and someone who believes in fairness and equality, I applauded (albeit with some reservation) the inclusion of Negro League statistics into the Major League Baseball record book.

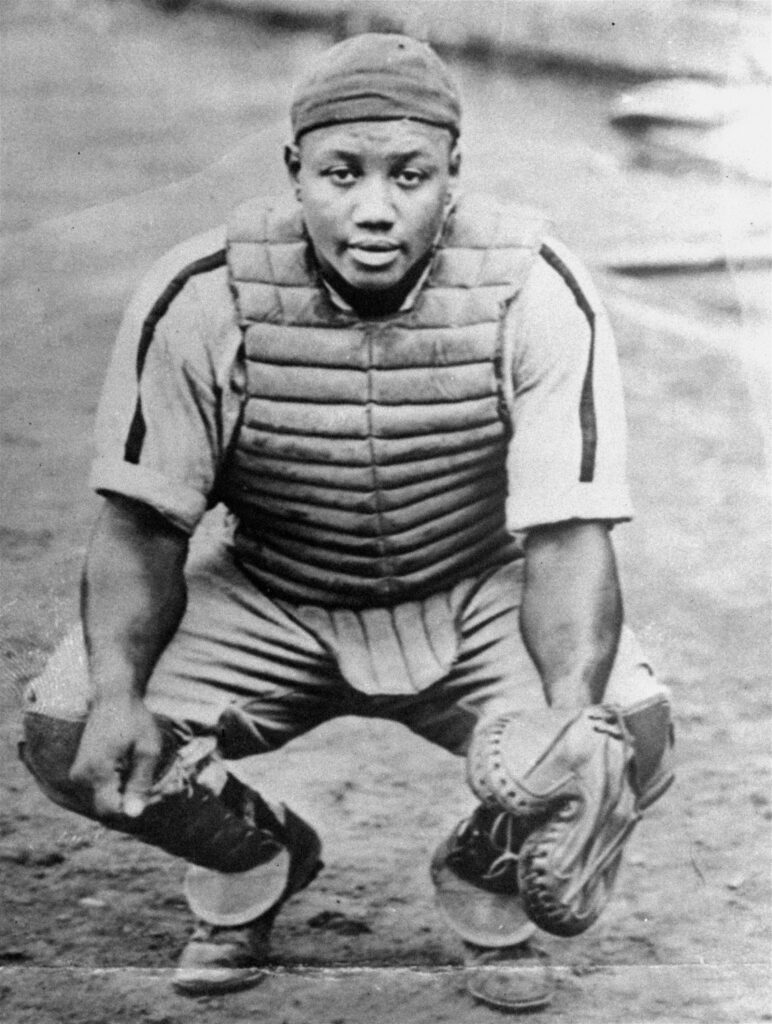

And so now, legendary Homestead Grays/Pittsburgh Crawfords slugger Josh Gibson is the all-time leader in batting averages at .372 and in career on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS), a measure of offensive statistics. Four other Negro League players are now in the top 10 in career batting average: Oscar Charleston (third, .363); Jud Wilson (fifth, .350); Turkey Stearnes (sixth, .348); and Buck Leonard (eighth, .345).

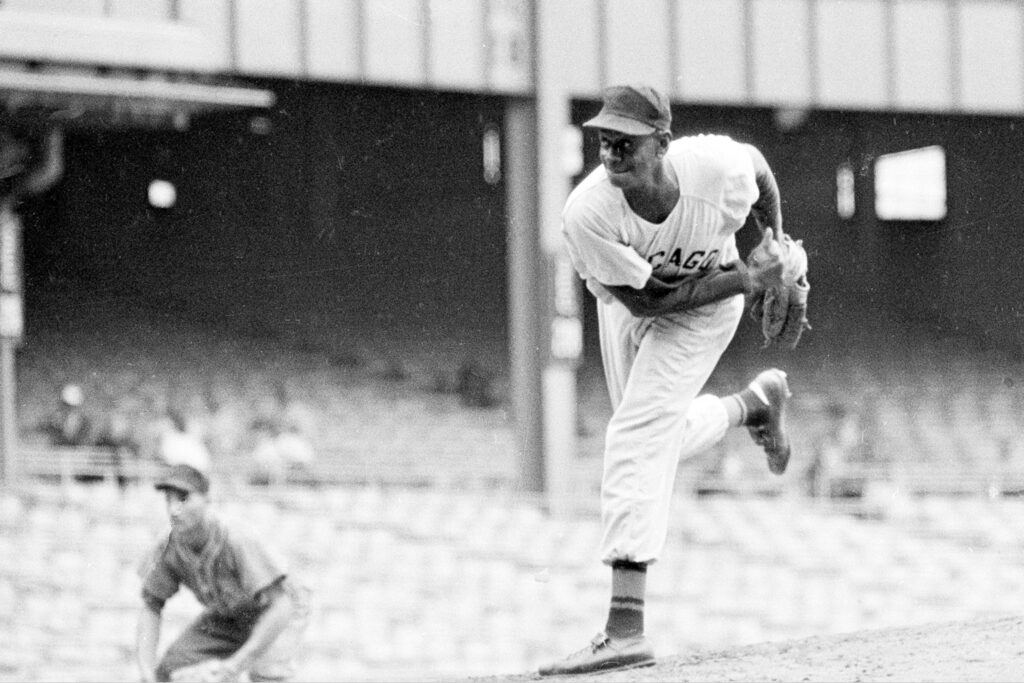

Seeing names like Satchel Paige on those newly constructed leaderboards makes you wonder how great the game of baseball would have been if those Black players had been allowed to play against the Ty Cobbs, the Babe Ruths, the Dizzy Deans, and Christy Mathewsons of the sport.

It would have revealed the strength of American diversity if everybody, regardless of race, were allowed to compete in the sport.

But in the ongoing reality of keeping Black people segregated from the fruits of the American dream, racism ultimately prevailed until Jackie Robinson broke the colorline in 1947, and that came with the gnashing of teeth and a swarm of racial slurs. As MLB was bringing in Black players to integrate the game, none of those former Negro League teams ever received compensation for the loss of their players.

Of course, the reaction to Major League Baseball — including the stats from the Negro League players who were not allowed to play because of the color of their skin — was predictable and quite familiar.

According to one tweet: “Liberalism is about destroying everything white people have accomplished and replacing them and their accolades.”

Another tweet from @TrumpOnMLB read: “The Woke MLB.”

The Woke MLB

— NHL Trump (@TrumpOnMLB) May 29, 2024

It has long been acknowledged that Negro League players were every bit as good as those white athletes who played in the Major Leagues, but they were not allowed to play. Boston Red Sox great hitter Ted Williams said so during his Hall of Fame speech in 1966.

From 1949 to 1962, 11 Black players, many of whom once played in the Negro Leagues, won National League Most Valuable Player Awards. That’s one of many pieces of evidence that shows how those players were just as good as their white counterparts.

RELATED: MLB hits delayed home run with Negro Leagues

For Black people, whether or not they are sports fans, that reaction is not surprising because it’s part of the same old history of America that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis doesn’t want taught in Florida’s classrooms and why some Southern states have introduced new and creative ways to make it hard for Black people to vote and have representation in federal and state elections.

Those reactions to MLB — including Negro League stats — as well as opposition to Black history in K-12 education and the constant demonization of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs — have me wondering, “What are these folks really afraid of?”

The answer to that question goes back to why a thriving Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921 was burned to the ground — another piece of history they won’t teach students in Florida. The white community was hostile toward Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street” because it succeeded economically and was capable of competing on equal footing with whites.

In his contribution to the 1619 Project, journalist Trymaine Lee tells the story of a successful Alabama Black businessman named Elmore Bolling who was shot and killed by white men because, as the Chicago Defender put it: “He was too successful to be a Negro.”

In 1892, Ida B. Wells-Barnett had to flee her Memphis, Tennessee, home because she wrote a story about three friends who were lynched for running a successful grocery store. Wells-Barnett’s newspaper offices were destroyed, and she was threatened with death if she ever returned.

For a nation whose creed claims that all men are created equal, it has collectively succeeded in making sure Black people aren’t included in that equation and they’ve done it by rigging the game in a variety of ways. That’s the reality America steadfastly refuses to face about herself.

While I do feel that including Negro Leagues stats is a step in the right direction on some level, I also find myself agreeing with what ESPN columnist Howard Bryant wrote about the proposal to include Negro League stats in 2020: “At some point, baseball, like the rest of the country, must wear what it has done to Black people.”

But that’s not going to happen anytime soon because rather than face the truth of systemic racism white America would rather deny, deflect, and suppress (as in the case of Florida disallowing the teaching of Black history in its schools) rather than heal the devastating wounds it has inflicted on Black Americans.