Three decades ago, Black journalists were akin to unwelcome tourists visiting the land of the Pulitzer Prize, American journalism’s most prestigious honor. At the announcement of the 2023 Pulitzer winners last week, Black journalists and authors were conspicuous and felt like property owners rather than refugees passing through. Consider:

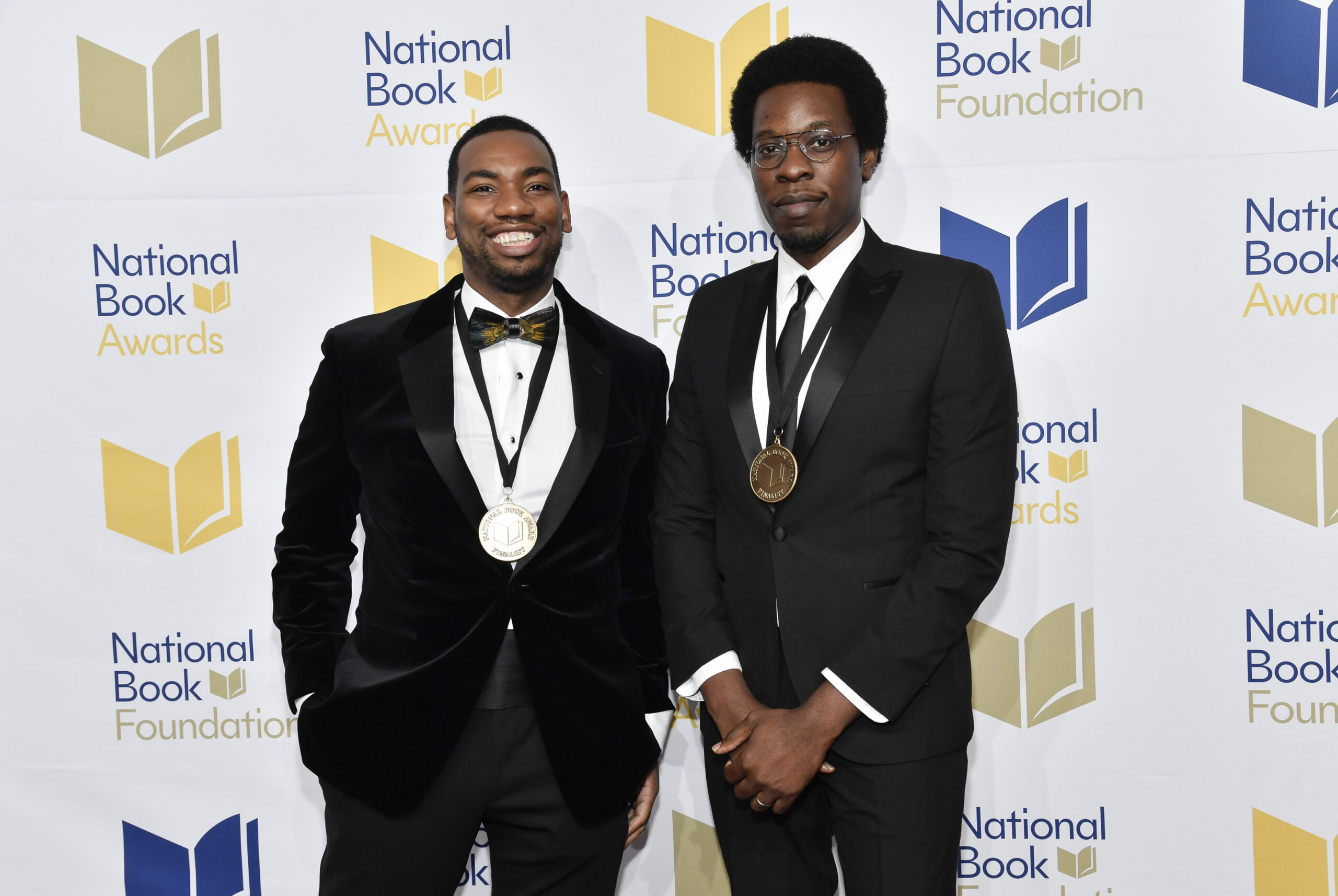

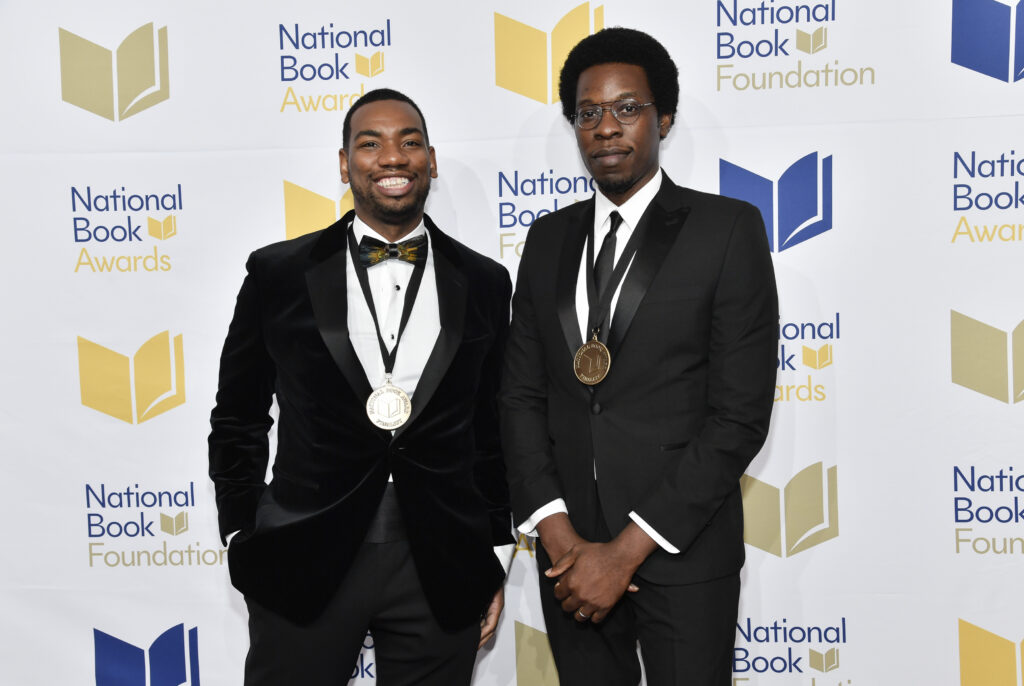

* Co-authors Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa won in the General Nonfiction book category for “His Name is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice”;

* Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels won in the Music category for “Omar,” an opera about enslaved people from Muslim countries, that “respectfully represents African as well as African-American traditions,” The New York Times reported, “expanding the language of the operatic form while conveying the humanity of those condemned to bondage”;

* Nancy Ancrum, editorial page editor of The Miami Herald, and board members Amy Driscoll, Luisa Yanez, Isadora Rangel and Lauren Constantino won for editorials that looked at the failure of Florida public officials to deliver on many taxpayer-funded amenities and services promised to residents over decades, the Times reported. The Herald editorial board was a repeat winner;

* The staff of The Los Angeles Times for a “revealing a secretly recorded conversation among city officials that included racist comments,” The New York Times reported, followed by additional coverage exploring racial issues in local politics. Kevin Merida, a Black man, and former assistant managing editor of The Washington Post who is now executive editor of The Los Angeles Times.

Other winning Pulitzer entries featured compelling subjects that were Black-themed. AL.com and Mississippi Today were co-winners in the Local Reporting category, for exposing how the police force in Brookside, Alabama, preyed on residents to inflate revenue. [The subject was an echo of incidents in Ferguson, Missouri, where an expose revealed law enforcement was used to prey on mostly poor, Black residents for revenue]. Mississippi Today was recognized for reporting on the former governor who steered millions of dollars of state welfare funds to benefit family and friends that included football champion Brett Favre.

AL.com won a second Pulitzer in the commentary category for “measured and persuasive columns that document how Alabama’s Confederate heritage still colors the present with racism and exclusion,” The New York Times reported.

To achieve this kind of racial inclusion required decades of documentation, struggle, and patience. In 1991 and 1992, the National Association of Black Journalists’ Women’s Task Force pressed for empowerment. At the request of Pulitzer Prize officials, the task force submitted names of two dozen Black American women who would be good candidates to serve as Pulitzer jurors or as members of the governing board,” I wrote in my 2003 book, “Rugged Waters: Black Journalists Swim the Mainstream.”

The request was made because Pulitzer Board Chairman Michael Gartner read “Black Women and the Pulitzer Prize” by Linda [Waller] Shockley that documented the limited participation of Black women in the Pulitzers at all levels – submissions, judging and oversight. In 1992, one Black woman sat on the 19-member Pulitzer Prize Board, and another lone Black woman served among 65 jurors.

The late Robert C. Maynard, then publisher of The Oakland Tribune and one of three Black people on the Pulitzer board, said he was optimistic that the minuscule Black footprint three decades ago would grow: “As more and more journalists of color get in the position where they can write major take outs [long-form writing], they will get more Pulitzer Prizes.”

As mainstream journalism has severely reduced its human and financial resources, Black journalists have moved into positions of leadership and authority in numbers that were unthinkable a half century ago. Last week, Nicole Avery Nichols was named editor in chief of The Detroit Free Press. Black women, both graduates of HBCUs, now run network news divisions at MSNBC, and ABC.

The George Floyd effect has influenced coverage of the Black condition and inclusion of Black journalists in decision making and storytelling. In writing their book, Samuels, 37, and Olorunnipa, 37, relocated to Minneapolis and Houston to spend significant time interviewing family and friends of Floyd, who was murdered sadistically in public by a Minneapolis police officer who pressed his knee to Floyd’s neck for an extended amount of time. The victim’s name became a rallying cry for racial justice.

“It was truly the honor of our lives to take this guy who everyone was OK with reducing to an image on a wall or a hashtag and showing he was flesh and blood and truly mattered to people,” Samuels told The Washington Post Tuesday. “Not in a theoretical way – his life mattered.”

Furthermore, by the time “His Name Is George Floyd” was published, numerous books that cited social science research showing racial injustices and racial disparities were being banned in schools and libraries in mostly red states. Samuels told The Post he hopes the Pulitzer recognition “helps to extend and revivify this necessary conversation that we need to have in this country, about the roots of our problems. To have this award support that kind of work means so much.”

The writer is author of two histories of NABJ and is a professor of professional practice at Morgan State University School of Global Journalism and Communication