Learning how to code so he can one day get a job working for a tech company is a relatively new passion for 32-year-old David Thornton, and so is studying court terminology and legal proceedings so he can also potentially become a paralegal.

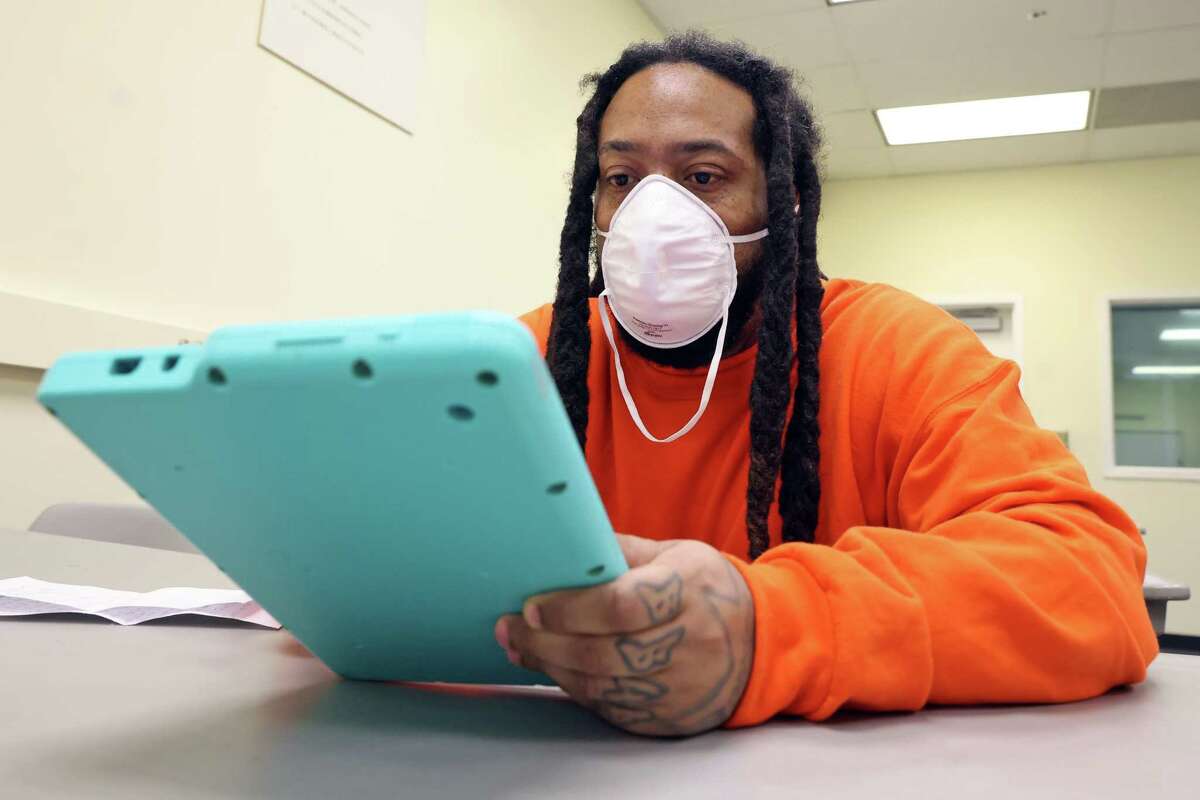

Thornton relies on a tablet computer to conduct his research, and he brought it with him when we met on Tuesday.

“Being able to have this information at your fingertips … it makes all the difference here,” he said.

Our meeting was at the San Francisco County Jail in San Bruno, where Thornton has been incarcerated for the past year. We talked in one of the jail’s sparsely furnished classrooms, where we sat on plastic chairs around a plastic table.

“This tablet helps a lot of us here focus on the future,” Thornton said.

San Francisco is providing free tablet services, which include music, movies, legal and employment resources, reentry guides and mental health information, to the incarcerated, the first program of its kind in the nation, city officials said.

As Thornton explained, the tablets provide ways for inmates to improve their mental health, and “focus on getting home and getting on the right path.”

Tablets are an increasingly common sight in American jails and prisons but most facilities generate revenue from them. Inmates get nickel and dimed — 25 cents for each email or electronic message sent and received, $2.50 to listen to a song, and up to $25 to watch a movie — and the fees often place unnecessary financial burdens on inmates and their families. Many of these inmates and their families are low-income and people of color.

While San Francisco’s new program ensures incarcerated people never have to pay these fees, local jails remain cold, harsh places where inmates are being punished for crimes a court system says they committed. But no person should be judged by their worst mistake, and everyone deserves a chance to change their lives for the better.

A successful criminal justice system should heal people, not find wicked ways to create more victims while fattening the bottom line of a $1.4 billion jail and prison telecommunications industry.

“Incarcerated people are not isolated, their whole family bears the burden and we have to keep those folks in mind, too,” said Anne Stuhldreher, the director of the Financial Justice Project in the Office of the Treasurer for the city and county of San Francisco.

The Financial Justice Project, along with the mayor’s and sheriff’s offices, the Public Library, and the San Francisco Jail Justice Coalition, collaborated on the program. The tablet’s entertainment options like movies, music, e-books come from the library free of charge.

The tablet program is consistent with the city’s attempts to reduce expenses for the incarcerated. In 2020 and 2021, San Francisco passed an ordinance preventing the city from making money off incarcerated people and their families; made jail phone calls free for local inmates; eliminated price markups on commissary goods; and implemented a commissary allowance program for the most needy inmates.

San Francisco’s criminal justice system isn’t flawless, but the way it humanizes inmates should be copied by the rest of the country.

Mayor London Breed has pledged $500,000 annually for the tablet initiative. Through a contract with Nucleos, a social issues-focused company based in Santa Cruz, the local jails will have access to approximately 1,400 tablets, more than enough to accommodate all inmates.

Tablet use in the jails is being strictly regulated, and inmates are allowed to browse only pre-approved forms of entertainment and rehabilitation-focused apps and websites. The tablets get checked out by inmates each morning and returned to jail staff each night.

While the tablet program is worth celebrating, it isn’t perfect. The inmates I spoke with complained they can’t contact their loved ones, particularly through video calls.

This is something the jails are working to rectify, Linda Bui, a lieutenant with the Sheriff’s Department and a watch commander at the jail, who has been involved in the design and implementation of the program, told me. Inmates won’t be charged for the service once it’s in place.

“That connection with family is important because it helps them think about the world outside of here,” Bui said. “The individuals who are in here are people, too.”

They’re people with families they hope to one day rejoin, which was clear when I spoke with inmate Phillip Pitney, 33. Pitney told me he’s been incarcerated for the last 14 years and has a 15-year-old daughter at home, and he said he’s been using his tablet to take parenting courses that have taught him about processing emotions and healthy decision-making.

“They can make you kind of emotional as a parent when you’re taking the classes. If I had taken classes like this before, I think I’d have been a better parent,” he told me. “You think about things you could have done better … and how you’re going to do them better.”

Reach Justin Phillips: jphillips@sfchronicle.com