When I was a kid playing youth football in the 1970s, I absolutely revered O.J. Simpson as a football player. From 1972 to 1977, Simpson was the NFL’s most dominant running back. In the years I played Little League football, I wanted to wear number 32 and was upset that the teams I played on never had his jersey available. But I always wore my blue number 32 as a practice jersey.

Given Simpson’s tumultuous life after his fame as a football player, sports commentator, and movie star, the only cheers that I can’t seem to get out of my mind came from Howard University students cheering his acquittal of murder charges in the death of his wife and her friend.

But the hard part about growing up is the harsh realization that our heroes are often flawed, sometimes disgusting, narcissistic human beings who are out of touch with reality — which oftentimes says more about the imperfections of American society than anything.

O.J. Simpson died on Thursday from prostate cancer at the age of 76 and leaves a complicated legacy of a celebrated and flawed life that put up a mirror to America’s ongoing contradictions with race, class, and the meaning of justice.

RELATED: O.J. Simpson dead of cancer at 76

If you choose to remember Simpson for his football mastery, he was one of the top running backs in college and the pros. In the race for the 1968 Heisman Trophy that he eventually won while playing for the USC Trojans, Simpson was in a fierce battle with Purdue star running back and safety Leroy Keyes. It was the first time in college football that two Black athletes were the frontrunners for the Heisman Trophy.

As the number one draft choice of the Buffalo Bills in 1969, Simpson had a pedestrian start to his career. By the end of the 1971 season, he underachieved to the point where some observers considered him to be a bust.

But the trajectory of Simpson’s pro career changed in 1972 when Lou Saban became the head coach of the Bills and decided that Simpson would be the focal point of Buffalo’s offense. For five straight years, Simpson rushed over 1,000 yards. In 1973, he ran for a then NFL record 2,003 yards — which made Simpson the first running back to rush for over 2,000 yards in one.

For his career, Simpson rushed for 11,236 yards and scored 76 touchdowns , 61 rushing and 14 passing. He was a five-time All-Pro and played in six Pro Bowls.

Simpson’s early years

Simpson, who grew up in poverty in the Black neighborhoods of San Francisco, became the first successful Black athlete to garner commercial endorsements. His most famous commercial was for Hertz Rent-a-Car in which he was the “Superstar in Rent-a-Car.” In those commercials, Simpson is seen running through the airport with adoring white fans chanting, “Go O.J., go.”

To many cultural critics, Simpson was the first, racially neutral Black crossover star who was seen as palatable to white people. He set the foundation for Michael Jordan, who would inevitably surpass Simpson as the darling race-neutral spokesman of commercial endorsements.

Simpson’s fame opened the doors for him to become a TV sports commentator for ABC and NBC and to star in movies, most notably, the “Naked Gun” series with Leslie Nielsen.

But Simpson’s life and legacy would be tragically sullied by the murder of his wife, Nicole Brown-Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman 40 years ago. On June 12, 1994, the bodies of Brown-Simpson and Goldman were found outside of Brown-Simpson’s apartment in the Brentwood area of Los Angeles.

O.J. Simpson, who was a person of interest, was supposed to turn himself in but ended up leading the L.A. police on a 60-mile, low-speed chase in a Ford Bronco driven by his longtime friend, Al Cowlings.

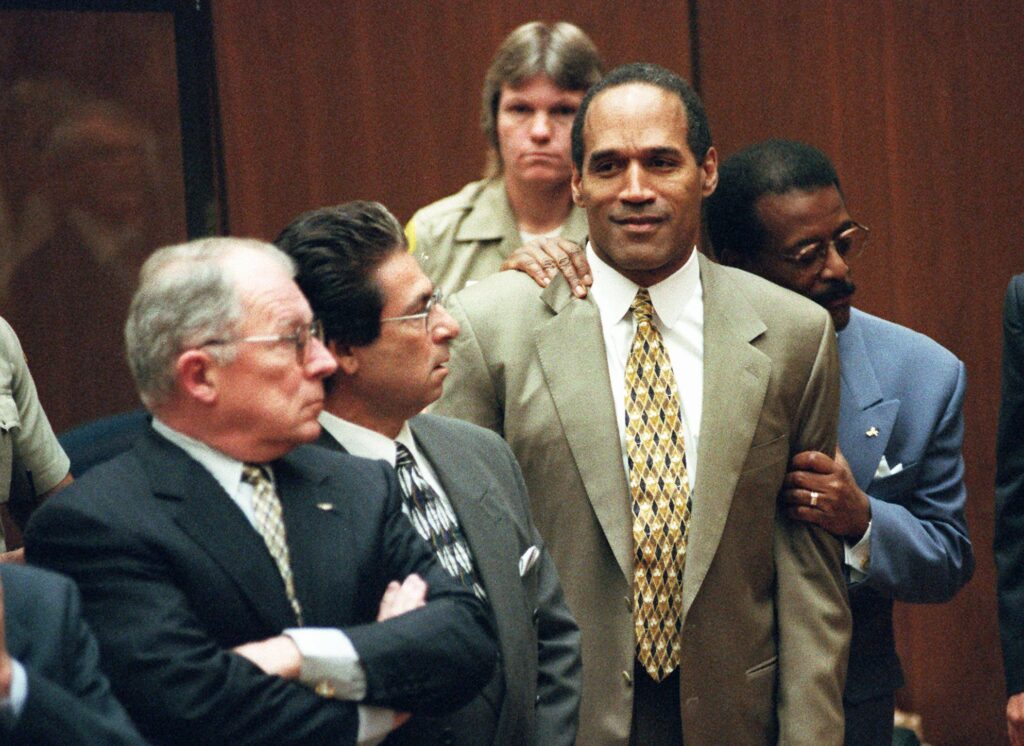

The so-called “trial of the century” was a cauldron of issues revolving around racism, police misconduct, domestic abuse, gender, and celebrity privilege.

The affluent Simpson employed a “Dream Team” of defense lawyers that included Johnnie Cochran, F. Lee Bailey, and Robert Kardashian who took on Los Angeles prosecutors Marcia Clark and Black prosecutor Christopher Darden.

Reaction to the trial and its outcome were divided along racial lines with Black people siding with Simpson and white people fervently believing that he murdered Brown-Simpson and Goldman.

The media coverage during those tumultuous nine months inadvertently gave rise to a new phenomenon in journalism—the celebrity media pundit—which you see on TV today.

When the trial ended in a not-guilty verdict, those who followed on TV heard that aforementioned cheer from Howard University Law School students but also witnessed the anger, hatred, and tears from white people. For me, that verdict truly represents how the insanity of racism has discombobulated this country.

For Black people, the reaction to the verdict wasn’t about Simpson on a personal level because Simpson, in no way, represented the paragon of racial virtue. You didn’t see him on TV protesting the Rodney King verdict or speaking out about it. You would never see O.J. at the cookout with the brothers and sisters.

In fact, even after his acquittal, you never saw O.J. Simpson giving away free turkeys in the ‘hood or wanting to help his people.

The verdict was more karmic retribution for generations of Black people who have collective memories of white men getting away with bloody murder in the killing and maiming of Black people. The words of the white defense lawyer defending Emmett Till’s killers said to the jury: “I challenge every last Anglo-Saxon one of you to find these men not guilty.”

That’s why Black people cheered so loudly for Simpson’s acquittal. They have been victims of a flawed and racist criminal justice system way too many times. But after the trial, Simpson stayed as far away as possible from the same Black community who believed he was innocent.

Three years earlier, the L.A. police officers who gave King a wood shampoo were acquitted by an all-white jury. Society told Black folks that the judicial process had spoken and to get over it. Despite O.J. being tried and found not guilty, a large number of white people still believe that Simpson is a murderer to this day and to think they thought he was one of the “good ones.”

A jury found Simpson liable in the civil suit and ordered him to pay $33 million to the Goldman family. In 2007, Simpson was arrested and served nine years for an armed robbery to get back his sports memorabilia.

In the end, there will be no debates about O.J. Simpson the football player who had dazzled the NFL with his prowess as a running back. It will always come back to whether or not he killed his ex-wife.