More than 60 years after the idea was initially broached, Swahili appears poised to become the language for all of Africa.

In the last decade, the African Union, an organization of the continent’s 55 countries, adopted Swahili as an official working language. It has been introduced in classrooms in South Africa and Botswana. In Uganda, the government recently allocated approximately $800 million in its budget for teaching Swahili in its schools. And universities around the continent, most notably in Ghana and Ethiopia, have recently begun teaching the language.

Swahili, which has about 200 million speakers and is one of the world’s 10 most popular languages, is the only African language recognized by the Southern African Development Community, a non-governmental organization based in Botswana. Swahili also is the official language of the East African Community, a coalition of eight countries.

Outside the continent, Swahili is also rising in stature. UNESCO, the cultural arm of the United Nations, recently designated July 7 World Swahili Day.

It is an important shift in a world in which English is the most widely spoken language overall. Despite this, Swahili has been the most commonly used language in Africa — even with two dozen African countries listing English as one of their main languages.

Proponents and linguists say adopting an African language as the continent’s lingua franca — or bridge language — would foster stronger business and cultural ties in one of the world’s ethnically and linguistically diverse continents while strengthening a sense of identity and cultural pride.

Language is power and it carries with it knowledge,” Leonard Muaka, an associate professor of linguistics and Swahili at Howard University, told Black News & Views.

“Swahili is a language that reflects and carries many of Africa’s cultures and practices,” Muaka continued. “Therefore, expanding the reach of the language will allow Africans to share the richness of the continent. The indigenous knowledge of Africans is lost through Western languages, but because of the closeness and similarities of the people of Africa, this African knowledge will be preserved both on the continent and the diaspora.”

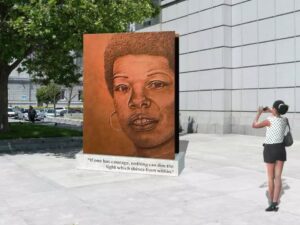

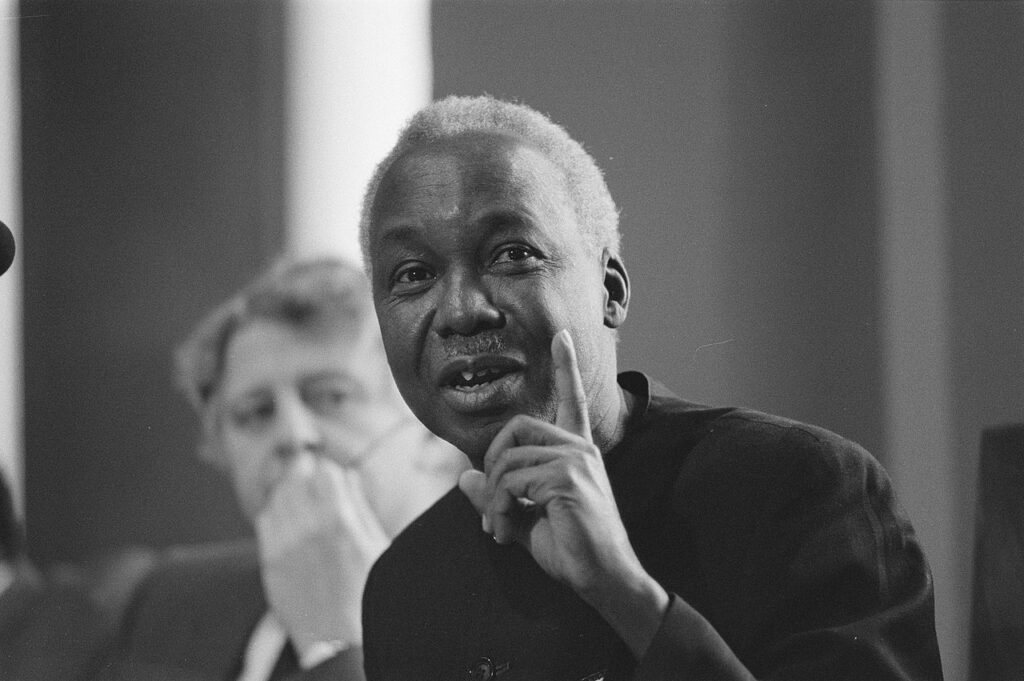

Following independence in the early 1960s, Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere used Swahili to unify his East African nation and championed the use of Swahili as a Pan-African language.

“Nyerere was unique in that he was able to use an African language as a unifying language in Tanzania,” said Elisabeth McMahon, an associate professor of history at Tulane. “The reason he was able to do that was that the Swahili language had already been a lingua franca as a trade language in the 19th century throughout areas of East Africa, so there were already people throughout the country who were bilingual. By no means were all people in Tanzania bilingual in Swahili and another language, but there was a significant enough number or percentage that allowed for that to happen.”

McMahon, a specialist in African history, added, “The other reason why Swahili was an effective choice was because Swahili people were a minority of the population of Tanzania. By using Kiswahili as a national language, Julius Nyerere was not prioritizing a particular ethnic group but rather offering a unifying language. It also helped that Nyerere himself was not Swahili.”

Supporters see Swahili as a way to unify Africa

Omolade Adunbi, a professor of anthropology and Afro-American and African Studies at The University of Michigan, said the impact of a continental bridge language could be far-reaching.

“Since independence, political leaders in Africa have always strived to look for a language that could better represent the continent as a lingua franca that is acceptable to the majority of Africans, ” Adunbi said. “That search for an African language identity has often involved Swahili and several other languages. More importantly, language as a unifier has always been a political project for the Pan-Africanist movement on the continent because once there is a language that is widely spoken among the majority of the continent, it would facilitate trade and bring the people closer.”

Efforts to make Swahili the continent’s common, bridge language predate the heady post-independence days of the early 60s, said Olufemi Babarinde, a clinical associate professor of global studies at Arizona State University’s Thunderbird School of Global Management.

“This effort could be traced to the Pan-Africanist movement and the concept of shared cultural unity that some agitators for the liberation of African countries … espoused in the post-Second World War era,” he said.

Most notable among the agitators was the late Nyerere, Tanzania’s first independent president, who not only used Swahili to promote the unity of independent Tanzania, but proposed it as a language for a United States of Africa that he and other Africans proposed in the early 1960s, according to Babarinde.

The educator added that the renewed impetus for Swahili — also known as Kiswahili — as Africa’s lingua franca was triggered by the African Union’s adoption of the language as one of its official working languages in 2004.

The diverse and widespread history of Swahili

Swahili was initially shared along the east coast of Africa by Arab traders hundreds of years ago. Its use was further formalized by British and German colonists in the region who adopted it as the language of administration and education. Despite its longstanding popularity on the continent, it faces stiff competition from the English language and European languages. English, French and Portuguese are the official or second languages of more than 50 of the continent’s 54 countries. Arabic is also widely spoken in North Africa and several other pockets of the continent. In contrast, Swahili’s dominance is largely confined mostly to East Africa, parts of Somalia, the western area of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mozambique. Its presence in West Africa, where indigenous languages like Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa and Fulah are widely spoken, is limited.

Mwatabu Okantah, professor and chair of Africana Studies at Kent State University, said adopting an African language as the continent’s lingua franca could have a profound impact on people of African descent in the diaspora.

“I subscribe to the idea that a basic and identifiable cultural unity exists within the diversity of African peoples but can also be applied to peoples of African descent throughout the diaspora.” he said. “I am of the opinion that adopting Kiswahili as a continental diplomatic language would allow African leaders to communicate with outsiders — Europeans, Americans, Asians, et cetera — with one mind and one voice. It would force non-Africans to translate African ideas, concepts and realities into their own languages.”