BUFFALO, N.Y. – One year after white supremacist Payton Gendron opened fire at a supermarket on Buffalo’s predominantly Black East Side, killing 10 Black people and wounding three other people, residents are facing the anniversary with fear and one even drives 10 miles out of his way to shop for groceries rather than enter that Tops Friendly Market again.

The trepidation has been so strong that Buffalo Common Council President Darius Pridgen recently gave accolades to the ministers, leaders, parents and others who’ve quietly “had to keep a lid on things for a year.”

Last year’s shooting marked “the darkest period in the history of Buffalo,” Mayor Byron Brown said.

Today marks the one-year anniversary of an act of violence by a 19-year-old with an automatic rifle that showed America the depth of anti-Black racism in this country. Shooter Payton Gendron is serving a life sentence, Tops has long since reopened and in March, New York State Gov. Kathy Hochul announced an infusion of $1.4 million in federal funding to go toward mental health services on Buffalo’s East Side. Local and national media outlets are camped out in the neighborhood looking for stories of strength, hope and healing.

But those are not the types of experiences that residents, returned store clerks and shoppers are sharing. Many are facing this anniversary with, frankly, dread.

They dread the media attention and requests to dredge up painful memories on-demand. They dread people expecting them to feel better when, for many, the memory is as fresh as if it had only been a week ago. They’re sour about the big-name visitors coming to deliver fiery speeches, collect an appearance fee, then flee before the lingering local sorrow has time to leave a stain.

“I’m not in a good place,” said Grady Lewis, a resident who unwittingly had a random chat with Gendron inside of the supermarket the day before the shooting.

Lewis told Black News & Views that he’s been in a funk for months.

“For this to be thrown in my face where I actually saw Black people get murdered and they’re not gonna do anything?”

Lewis has seen no serious change in how we talk about gun ownership, no changes in how Black history is taught, and only the shallowest efforts to address racism.

Lewis watched incredulously from directly across the street as the shooter returned and opened fire in the Tops parking lot.

“I was 30 seconds away from being [killed] and you’re gon’ ring a bell for me? Nah, my life is worth more than that, and I know that [the deceased are] worth more than that.”

This weekend, tributes and another round of food give-aways are taking place.

”They’re giving us free stuff, how is free stuff going to help me? Teach me how to fish so I can get my own.”

Lewis is heartbroken, he said, that the message to our young people is if you get shot, you’ll get a free hot dog.

“I can’t even imagine being 7-years-old thinking, ‘Is this what life is about?’ “

The funds that Hochul announced will help, but more meaningful change is needed, he said.

“Mental health is great, mental health is what we need. But after you are mentally stable, I come back outside to the same world to turn bat crazy again? Constantly being in fear for my life?”

James, a Black U.S. Army veteran and retired corrections officer, declined to share his full name because answering media questions last year brought threats of violence to his door.

He chose to pursue the military and law enforcement because he’d seen police brutality first hand and wanted to have a role in a system where he could make a difference. He said he saw overt white supremacist actions by people in power everywhere in the military and watched as they transitioned into every extension of law enforcement.

“I’ve been all over the U.S., and I dealt with men like [Tops shooter Payton Gendron] all the time,” he said, echoing Lewis’s sentiment that the shooting left him feeling devalued.

James noted with frustration that gun buy-back and amnesty efforts always seem to be targeted towards Black communities when this event proved that perpetrators can be anyone, anywhere, any time.

“How are we supposed to believe ‘all men are created equal’ when every day they’re telling you you’re not?” he asked.

Kenny Ivy is a local businessman and retired FBI agent who contracts with law enforcement agencies all over the country to teach about firearms. He expressed ambivalence about the upcoming anniversary.

While he disagrees with the faction believing the market should not have reopened on that site and applauds Tops for its commitment to remaining in the area, he still can’t bring himself to cross its threshold. He just has “too many emotions,” he said. “The travesty of people being killed just shopping and trying to feed their families …” he added, his voice trailing. Though he lives just a few blocks away, he drives 10 miles to another supermarket to buy groceries.

“I’m saddened by our country’s behavior. The sheer volume of these mass shootings just…saddens me. Is this our current state of affairs? Is this really who we are now?”

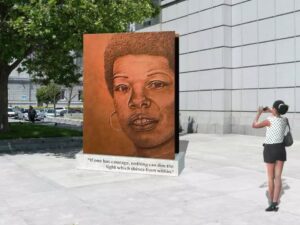

He is roused, though, by plans in the works for a permanent memorial to the fallen and eager to see how they come to fruition.

Mayor Brown, in addressing the public, said he’s been encouraged by how people have responded to the trauma.

“I’m glad to see our community come together as a national, and international, model of strength and resilience,” he said. “A white supremecist came here intent on killing as many Black people as possible. It only left us with a greater sense of resolve to focus on fighting white supremacy and hate.”

Pridgen, in addressing the community, said, “This could have been a powder keg of violence, of negative reactions and there were some people in Buffalo … there were brothers ready to go, and ready to retaliate.”

Instead the message that came from East Buffalo was “we’re not going to act like the shooter.”