From the moment Amara Harris was accused of stealing another student’s AirPods at Naperville North High School, she has insisted it was a mixup, not theft. She got a ticket anyway and is still fighting to clear her name.

She told a school dean that she thought the AirPods were her own, having picked them up a few days earlier in the school’s learning commons, where she said she thought she had left her own set. Her mother repeatedly told officers that her daughter hadn’t stolen the wireless earbuds, records show.

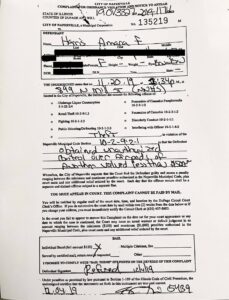

Still, the school resource officer wrote Amara a ticket in 2019 for violating a municipal ordinance against theft. Paying a fine would have made the matter go away, but Amara says she won’t admit to something she didn’t do. For two and a half years, she has repeatedly gone to court to assert her innocence, even delaying her plans to attend on-campus classes at her dream school, Spelman College.

Now, in a rare and dramatic example of the impact of school ticketing, the case is headed for a jury trial, with the next court date on Tuesday. As Naperville continues to prosecute the case, Amara and her mother have racked up far more in legal bills than the city’s highest fine would have cost them.

“I am innocent. I am fighting because I don’t want this to happen to anyone else,” said Amara, now 19. “Why would I say I’m innocent to everyone but then I lie in court and say I’m guilty? It doesn’t make sense to me.”

This spring, in the investigation “The Price Kids Pay,” ProPublica and the Chicago Tribune exposed the widespread practice of school officials and local police working together to ticket Illinois students for misbehavior at school, resulting in fines that can cost hundreds of dollars. Reporters documented about 12,000 tickets issued for possession of vaping devices and cannabis, disorderly conduct, truancy and other violations from August 2018 through June 2021.

[ Read the investigation: Schools and police punish students with costly tickets for minor misbehavior ]

Ticketing students for their behavior in school skirts a state law that bans schools from disciplining students with monetary fines. Immediately after the report was published, state officials including Gov. J.B. Pritzker and the state schools superintendent said they intended to put a stop to the practice.

The superintendent, Carmen Ayala, chided schools for outsourcing discipline to police and urged them to stop. The Illinois attorney general’s office, concerned that school ticketing was violating the civil rights of students of color, launched an investigation into a large suburban high school district and said it might investigate others.

But none of the state officials addressed how to deal with pending cases of students who, like Amara, had already been ticketed.

“The governor says he wants this to stop, he wants this to end,” said Amara’s mother, Marla Baker. “We are in the middle of it.”

Amara’s family, like so many others, was thrown into a system that uses a lower standard of proof than a criminal court. People ticketed for ordinance violations can be held responsible if the allegation is deemed more likely to be true than not, and the ticket itself is considered evidence. At every turn, the system and the officials in it encourage families to admit liability and pay a fine. And most do.

During a year of reporting on student ticketing that included attending more than 50 days of hearings, Tribune and ProPublica reporters met dozens of students and parents who paid fines even though they believed police didn’t need to be involved in the first place. Some were initially inclined to fight the citations but eventually gave up, worn down by the process.

Amara’s case demonstrates the extraordinary effort it can take to argue against a ticket in a system built for assembly-line justice. Hers is the first case the Tribune and ProPublica have encountered that could go before a jury; Naperville officials said the city hasn’t had a jury trial for an ordinance violation in at least a decade.

The ticket is a civil matter, so there’s no threat of jail time. But Amara said she is committed to clearing her name.

To Amara and her mother, the ticket — and the city’s commitment to prosecuting it — is another example of people in power discriminating against Black children. Only about 120 of the roughly 2,700 students at Naperville North are Black, and Baker has spoken out in the past about what she sees as racism and bias in the city’s schools.

A Naperville city spokesperson, responding on behalf of the city and its police department, said “the City categorically denies that race in any way played a factor in this case.”

[ Black students far more likely to be ticketed for school behavior ]

Spokesperson Linda LaCloche declined to answer specific questions about the police investigation because Amara’s case is pending. The spokesperson attributed the case’s slow progress to court closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Amara’s change in attorneys and court scheduling issues, among other reasons.

The officer who wrote the ticket, Juan Leon, declined to discuss the case but said it was “unbelievable” that it was still pending. He blamed Baker for dragging it out.

A Naperville Community Unit School District 203 spokesperson distanced the district from the case, saying: “Naperville 203 does not ticket students.” Spokesperson Alex Mayster said school officials rely on school resource officers, who work for the city’s police department, when a disciplinary matter may involve a law being broken. State schools chief Ayala has said schools that take this approach are “abdicating their responsibility.”

Amara’s family so far has paid at least $2,000 in lawyer fees to fight the case, Baker said. She and Amara stopped working with their most recent attorney in part because of the cost of going to trial and his recommendation that they accept a plea deal.

If there’s a trial, Amara may have to defend herself. Still, she said, she is not going to quit and allow the ticket to blemish her hard-earned school record. She made the honor roll at Naperville North, participated in school activities including cheerleading and the step team, served as an aide in the classroom and for the school deans and, in 2020, graduated from high school ahead of schedule. She said she has interned at the Brookfield Zoo and hopes to become a veterinarian.

“They are taking away all of my accomplishments that I have worked hard for and substituting it with an accident that happened,” she said. “To define me as a person — that is not who I am.”

This investigation is a collaboration between ProPublica and the Chicago Tribune.