San Francisco Chronicle

What started as a rally cry in the wake of the police shooting of 23-year-old Rob Adams in Southern California has turned into a meal-time ritual for a grieving family.

When he sits down to eat with his young siblings, Kayden Adams, 8, begins reciting the chorus he learned at protests in support of his dead brother. Soon, they all join in a song-like chant.

“Justice for Rob, justice for Rob…”

“The kids just start singing it,” said Robert Adams, Rob’s father, in a phone interview with The Chronicle. “Rob’s last little sister and his little brother, they just get to singing, ‘Justice for Rob,’ and my little baby, she just blend in with ’em — ‘Justice for Rob.’

“As I’m saying it to you now, I’m sitting here in tears. It hurts, and I know nobody wants to hurt like this. That’s all we’re seeking, is justice, and somebody be held accountable for their actions.”

If the family does achieve the justice it seeks — last month their attorneys filed a $100 million lawsuit against the City of San Bernardino — it will be with an assist from a person who has become more famous for his social-justice crusading than for his NFL quarterbacking heroics: Colin Kaepernick.

Searching for answers after police shot Adams to death on July 16 in a parking lot, the family connected with Kaepernick’s Autopsy Initiative, which provided an independent autopsy on Adams. It found he had been shot seven times, primarily from behind.

Police say the shooting was justified because Adams had pulled out a gun and they feared he would open fire, but the family says the object was a cellphone.

The program, launched in February by Kaepernick’s non-profit Know Your Rights Camp, provides free secondary autopsies for families of men and women killed at the hands of police, or who die while in police custody. Second autopsies are not uncommon, but the Autopsy Initiative is believed to be the only free provider of the service.

“Oh, it’s unique,” said Dr. Roger Mitchell, a nationally noted forensic pathologist and member of the Autopsy Initiative’s five-person board. “This (service) absolutely doesn’t exist outside the Autopsy Initiative.”

The purpose of the program, Kaepernick said to the Associated Press, is to ensure “that family members have access to accurate and forensically verifiable information about the cause of death of their loved one in their time of need.”

Since then, the media-averse Kaepernick has declined to comment, but members of his organization are willing to explain.

“Some (victims’) families can’t sleep, they can’t eat, they can’t do anything because they know nothing,” said Nicole Martin, the Legal Program Director of the Autopsy Initiative (AI). “All they know is that their loved one is dead, and they have no answers. It’s them against the world. That’s why it’s so important for us to be that source of trust, because they’ve been let down, as far as who they can trust.”

Autopsies in police-related deaths are routinely performed by government entities. Often the findings of those autopsies are not available to the families for many months, and are subject to potential bias, conflict of interest, carelessness and even dishonesty, some experts say.

The initial autopsy of George Floyd, for instance, ruled that Floyd died from heart disease and drugs. A second autopsy, conducted by an independent pathologist hired by Floyd’s family, ruled that he died from asphyxia caused by police restraint. The officer who knelt on Floyd’s neck for several minutes was convicted of murder.

Without a second autopsy, Mitchell said, “It’s going to be justice based on what you can afford and what you have access to.”

Ben Crump, a noted civil rights attorney who represented the family of George Floyd, and who represents the family of Rob Adams, told The Chronicle that most families can’t afford a second autopsy, which can cost between $3,000 and $10,000.

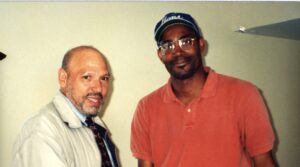

“They just have to live with whatever the state or medical examiner says,” said Crump, who met Kaepernick when he (Crump) was invited to speak at Know Your Rights Camp. “The Autopsy Initiative is a great leveler of the playing field, is what I believe.”

Kaepernick knows about unlevel playing fields. He was a San Francisco 49ers quarterback from 2011 to 2016, leading them to the Super Bowl after the 2012 season. The 49ers released him when he was 29, and he has received no NFL offers since.

Many feel Kaepernick is a pariah among NFL team owners and coaches because he knelt during pregame national anthems in 2016, protesting social injustice and police brutality. Even though he announced after that season that he would no longer protest in that manner, he remains an NFL outcast.

In 2017, Kaepernick and former 49ers’ teammate Eric Reid sued the NFL for colluding to keep them out of the league, and settled for an undisclosed sum.

Kaepernick, now 35, continues to do football-related workouts five days a week, preparing for another opportunity to play in the NFL.

Meanwhile, he is a full-time activist. In his final season, Kaepernick donated $1 million to grass-roots social-justice organizations, and co-founded, with his wife Nessa Diab, the Know Your Rights Camp, empowerment and education camps for disadvantaged youths. It became an umbrella organization that includes the Autopsy Initiative.

“Colin is involved (in AI) very step of the way,” said Ben Meiselas, general counsel for Know Your Rights Camp.. “He routinely speaks with the pathologist and with the AI leadership. He ultimately directs all actions and makes all final decisions for the AI.”

As of December, AI had completed 41 second autopsies. AI makes no attempt to determine innocence or guilt, nor does it provide legal advice or assistance. But at least three AI autopsies have been precursors to lawsuits. The Adams family’s suit is the largest of those three, and that case presents a picture of the system, and of the Autopsy Initiative at work.

The Adams family learned about AI from Crump and Bradley Gage, a Los Angeles attorney who is handling the case with Crump. Crump and Gage took the Adams family’s case, then suggested they seek AI’s assistance, but many attorneys will not take on a case without seeing a second autopsy.

Gage said, “We can only take on the most meritorious cases, and this initiative helps… us to evaluate and determine what are the cases where there was excessive force, where there was not justification for that force, and the cases where the police acted appropriately.”

San Bernardino police say they were responding on July 16 to a call about a Black man armed with a handgun. Surveillance videos show Adams standing in a parking lot as a gray unmarked police car stops about 30 feet away.

Adams pulls an object out of his waistband. He takes several slow steps toward the car. As two officers jump out of the car and aim handguns at Adams, he turns and runs between two parked cars, toward a wall. Police body-camera video shows one of the officers shooting at Adams as he flees. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Police say a loaded handgun was recovered at the scene. Adams’ mother says she was talking to her son on the phone as the incident occurred and says that the object in his hand was his phone.

Rob’s father said he initially heard, from his sister, that his son had been shot twice, in his leg and his arm. At the hospital, the father said, the family was kept waiting for at least six hours, with no information on Rob’s condition. Finally, a sheriff’s deputy informed the family that Rob Adams was dead.

“She didn’t say how it happened,” Robert Adams said. “She said it’s under further investigation, and she wouldn’t let us see him or anything. She would just let us touch the little body bag and say our farewells to him.”

Robert Adams said the coroner’s office declined to provide information, and that his request to identify his son was denied. The only information the family received was from a video statement released publicly by the police department.

In the video, San Bernardino police chief Darren Goodman said, “Officers briefly chased Adams, but seeing that he had no outlet, they believed that he intended to use the vehicle as cover to shoot at them.” He added that Adams had a criminal history and was on probation for an armed robbery conviction.

About three weeks after Rob Adams’ death, a second autopsy was provided by the Autopsy Initiative. The AI pathologist found seven bullet wounds in Adams’ back, arms and legs.

“The bullets appear to have first struck him in the back, causing him to be turned from the impact resulting in the further shots to the side,” Gage said.

Crump and Gage then filed the $100 million civil rights lawsuit on behalf of the family. (Any criminal charges against the officers would have to be filed by the county district attorney.)

“It’s an unusually large amount,” Crump said, “and we did it intentionally, because what we’re trying to do is send a message that you can’t keep shooting unarmed Black people in the back while they’re running away, posing no threat to you.”

Did the second autopsy contradict the findings of the initial autopsy? Unknown. More than five months after Adams was shot to death, the initial autopsy report had not been made available to the family and its attorneys.

Such delays are a routine obstacle for families seeking answers and justice. By the time the AI had conducted its first 32 autopsies, about eight months into the program, the initial autopsy report had been made available in only six of the cases.

Delays not only prolong the anguish for families, but can be harmful in a legal sense. There are time widows, varying from state to state, for the filing of suits.

“They’re claiming (in the Adams case) it takes them over a year to write a report, which is utterly absurd,” Gage told The Chronicle. “When they make such a claim, it delays our ability to find out the truth…. In my opinion, they’re covering stuff up. There’s no justification or valid excuse to take so long. And when we contacted the coroner, they said they were told not to provide us with the autopsy, based on instructions from the police department. So it’s pretty clear in my mind, at least, that it’s a cover-up.”

The San Bernardino County coroner’s office said it is standard procedure to not release an autopsy report while a homicide investigation is ongoing. A spokesperson at the office said the turnaround time for autopsy reports is six months to a year, partly due to staffing shortages.

Now that the Adams suit has been filed, the attorneys are able to subpoena the first autopsy report.

The autopsy system tends to promote controversy, consternation and contention.

“There is often a lot of bias within the first autopsy report,” said AI director Martin. “Sometimes the police who are involved in the death are present within that coroner office’s room, or have relations with that coroner’s office…. There’s also the use of faulty forensics.”

Martin said one AI pathologist found a bullet in a body that should have been removed during the first autopsy. In another case, she said, the family was told that the first autopsy had been performed, but the AI pathologists discovered that there had been no first autopsy.

While some may see AI as an anti-police service, Gage pointed out that he also represents police officers, and that AI can serve as a deterrent that benefits the police, too.

“We can help to avoid tragic deaths, and improve the situation, not just for the victims, but also for the good police officers that get dragged down by the actions of the bad,” Gage said.

It’s all about truth and justice, and as Norico Martinez discovered, battling the system in search of truth and justice for a loved one can be a daunting task. Her mother, Lisa Martinez, age 55, died last May while incarcerated in Greeley, Colo., facing drug-possession and money-laundering charges.

“I got so many different stories from that jail,” Norico Martinez told The Chronicle.

She said she found and photographed cuts and bruises on her mother’s body at the hospital on the day her mother died and received conflicting information.

“I decided I needed to put my grieving on hold and I need to fight for my mom,” Norico Martinez said. “Something’s not right.”

That feeling was reinforced when Martinez got her mother’s autopsy report about a month later. Cause of death was ruled to be dehydration and pneumonia.

“I knew in my gut and heart I couldn’t trust the county corner, being she passed away in the county jail,” Martinez said.

Martinez contacted several attorneys but was told they wouldn’t take the case without seeing a second autopsy, which, she was told, would cost between $10,000 and $15,000. Then one attorney told her about Kaepernick’s Autopsy Initiative.

Martinez phoned the Know Your Rights Camp office on a Friday, heard back immediately, and by the following Tuesday her mother’s body was being transported to a second autopsy. The AI pathologist ruled that the cause of death was homicide due to strangulation.

“I always knew in my gut that something happened to my mom, and without them (AI) I would have never gotten those answers,” Martinez said.

Martinez and her attorney are waiting to see if the county district attorney will file charges.

“It’s not, like, for money,” Martinez said of her reason for pushing for legal action. “No. I want somebody arrested and charged for what they took from me.”

Neither Norico Martinez nor the family of Rob Adams dealt directly with Kaepernick, but both had praise for him and for the service provided.

“People don’t just come out and do things for people these days,” Robert Adams said. “It was a blessing. I watched him all through his career, and I know how he’s trying to (correct) anything that’s going wrong in our world.”

Martinez said she was struck by the kindness of the AI staff.

“They’re truly amazing people, they were truly comforting,” Martinez said.

That included the driver hired by AI to transport her mother’s body to the autopsy. The driver asked Martinez about her mother, and Norico said that Lisa Martinez had hated fast driving, and that she loved country music.

“OK,” the driver told Norico Martinez. “I will drive under the speed limit, and your mother and I are going to listen to some county music.”

Scott Ostler is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: sostler@sfchronicle.com