Playwright August Wilson died of liver cancer on Oct. 2, 2005, in Seattle. He was 60, and the “theater’s poet of Black America” was experiencing a rising celebrity. His work gave voice to 100 years of Black history and struggle.

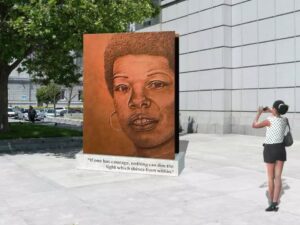

On April 27, Wilson would have turned 79. Since his passing, his reputation has only grown. This is most visible in his hometown, Pittsburgh, where three pillars have emerged that cultivate his legacy. Downtown’s August Wilson African American Cultural Center features The Writer’s Landscape, a permanent exhibition of Wilson’s life and plays. Just up the hill, the home where he was born has been restored as August Wilson House, now functioning as a community arts center. It’s only the third such honor for a Black male writer in America. And, not too far away, the University of Pittsburgh houses the playwright’s archive, which is drawing international attention.

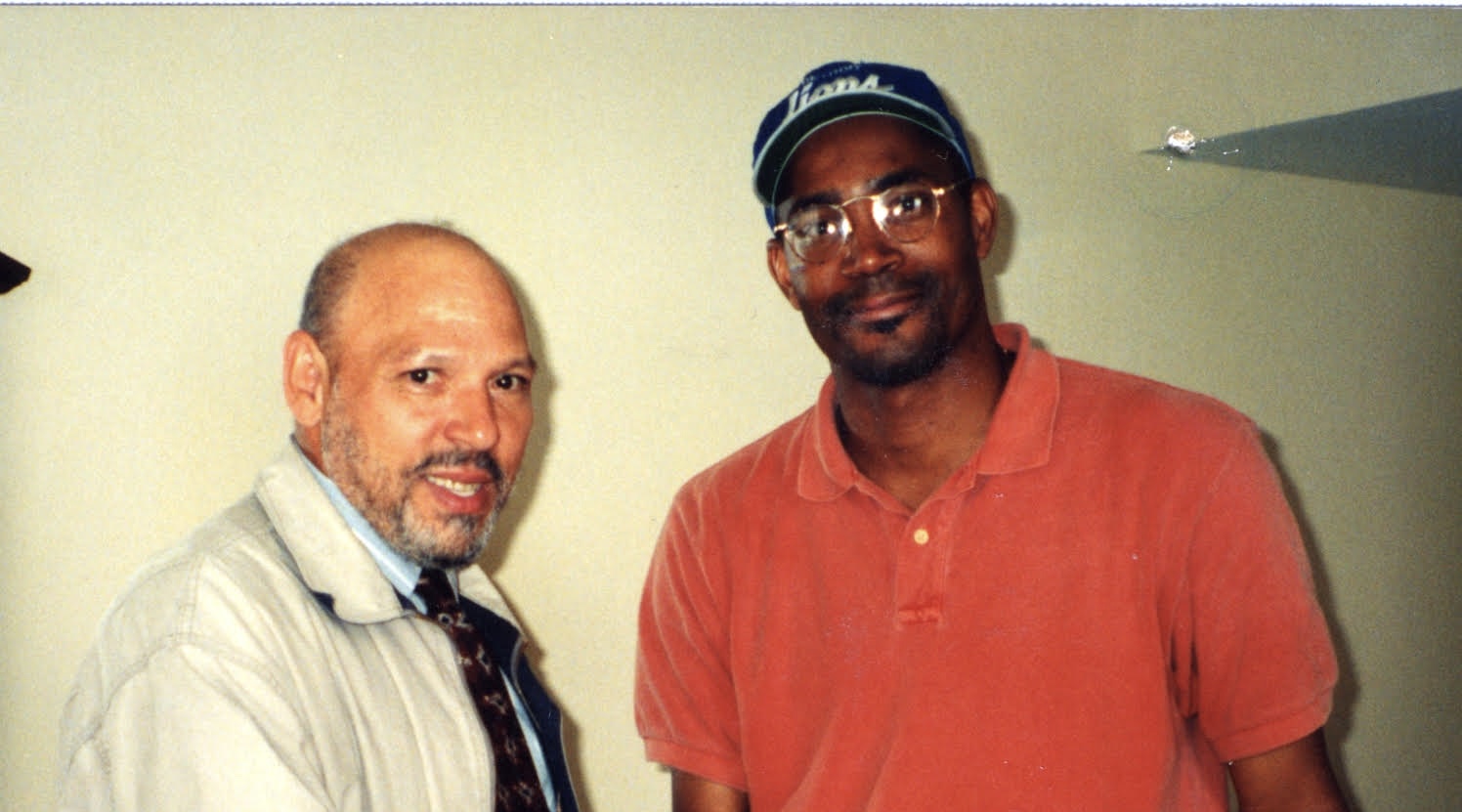

Some 25 years ago, I was a reporter with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and had the chance to sit with and interview Wilson at a downtown restaurant. In 2002, I began to write a story about his growing influence. I never finished it. Recently, cleaning out my computer, I found the draft. In the time that’s passed, I’ve become board president of August Wilson House. I thought I’d share the draft, as it reflects on the playwright and the influential figure he was becoming. All of the information and professional titles reveal the work and perspectives of each source at the time the piece was originally drafted. The article has been edited for clarity.

PITTSBURGH 2001 — He looks like any other Pittsburgh resident strolling through the crowded lunchtime street. Natty in his burgundy turtleneck and tweedy gray sports coat, August Wilson, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright slips into the noisy diner unheralded and unnoticed.

That was 18 months ago when Wilson was in his hometown to inaugurate a new $20 million theater and premiere his latest play, “King Headley II.”

Since then, it’s only grown more difficult not to notice Wilson. In April [2001], the dark and tragic “Hedley” opened at Broadway’s Virginia Theater. That was after the play had garnered respectable reviews and capacity crowds in Los Angeles, Boston and Chicago.

In its travels, “Hedley,” the 1985 saga of a son desperate to succeed and overcome a blood-stained past, drew in some of theater’s brightest stars: Laurence Fishburne (in a Seattle workshop), Ella Joyce, Tony Todd and Richard Brooks. Tony-winner Brian Stokes Mitchell plays Hedley on Broadway and veteran actress Leslie Uggams portrays his mother. Leading Black director Isaac McClinton has been on board since the play’s premiere in Pittsburgh.

With each success, it gets tougher for Wilson to shun the celebrity life.

Whenever possible, Wilson opts to spend as much time as possible with his new wife, Colombian-born Constanzo Romero, and toddler daughter, Azula Carmen, in their home in Seattle. For those who know and work with him, this fits his M.O. He’s a gentle spirit who prefers to keep a low profile.

“He’s very quiet,” said playwright and actor John Henry Redwood. A veteran of five of Wilson’s plays, Redwood first met Wilson nearly 11 years ago and recalls he rarely solicits attention.

“There are so many demands on his time,” said Redwood. “Staying out of the limelight is one way he gets time to himself.”

However, for a man who’s been heralded as a savior of Black theater, Wilson can’t completely avoid the spotlight.

This year [2002], his powerhouse “Fences” plods toward the big-screen. Sold to Paramount Studios in 1987, the play – the story of unfulfilled dreams of a frustrated garbage collector and his defiant son – has been delayed on film while Wilson holds out for a Black director and continues to chip away at the screenplay. He promises to finish it soon and hopes for production to start before the end of this year.

It’s not like he doesn’t have anything else to do.

In the past 17 years, he’s had seven plays on Broadway, won an Emmy for the television version of “Piano Lesson” and unveiled “King Hedley II,” his eighth play in a 10-play cycle meant to chronicle every decade of 20th century Black America. Wilson’s career remains on the upswing.

“I haven’t been sitting by the telephone, man. I’ve been doing my thing, ya know,” said Wilson, chain smoking his Marlboro Lights between sips of his coffee.

The legacy of Wilson’s work

Wilson’s perceptive, poetic intelligent playwriting spawns its own following among theater’s elite and emerging lights.

“Oh, he is so important,” said Oni Faida Lampley, a playwright and actress. “His work has been so groundbreaking that is inevitable that American theater and writers and actors of color would be influenced by his work.”

Lampley, in 1992, took over the role of the emotionally and physically scarred waitress, Risa, in Wilson’s Broadway run of “Two Trains Running.”

“He showed that Black language could be welcomed,” said Lampley, whose respect for Wilson came while she was an acting student at New York University and saw “Fences.”

“The first thing that touched me was the set,” she said. The simple placement of a radio on the back porch told her that “somebody had seen us and said our lives are theatrical, too.”

Others, like Redwood, have a first-hand look at Wilson’s generosity.

For his first foray into a Wilson play, Redwood was in Pittsburgh in 1989 preparing for the lead role of Troy in “Fences.” Redwood, a tree trunk of a man, felt modest in the presence of Wilson, who by that time was afforded a reverence for his success and had come to town to see the play in rehearsal.

Here’s what worried Redwood. His own spiritual convictions prevent him from uttering the Lord’s name in vain. So, the director had to ask Wilson if the script could be changed. For some playwrights – including Wilson, who’s fiercely protective of his words – altering the script can be a touchy subject. In this instance, said Redwood, Wilson made an accommodation.

“Right off the bat,” said Redwood, “the word came back down to me to just say ‘damn’ if you want. Mr. Wilson is very courteous. He will tell you if something doesn’t work, but it is not totalitarian. He doesn’t make you feel little.”

Keith Glover, a young dramatist, speaks highly of the playwright, too.

“August showed me there was room for the real deal on stage. I was seeing plays that weren’t speaking to me. Hearing August say you don’t have to lose your integrity made me get back behind a typewriter, knowing that you have to be as brave as he had been.”

Praises flow from actor-producer Laurence Fishburne, as well.

In the early ’90s, while taking a break from auditions in Los Angeles for “Two Trains Running,” Fishburne ran into Wilson, who was outside smoking a cigarette.

He would go on to develop a relationship with Wilson and would be mentored by the playwright. Over the years, Wilson personally recognized Fishburne’s work in his plays and encouraged him as a writer.

“I really think of him as father-brother,” said Fishburne, and look to August as an example of what is possible as a writer. I know I have something to shoot for.”

In 1992, Fishburne won a Tony for his role as Sterling in “Two Trains Running” and delivered an acceptance speech that impressed Wilson.

“That’s when I peeped his personality,” said Fishburne, who added that Wilson subsequently charged the actor to do his own writing. Two years later, Fishburne wrote his first one-act play, “Riff-Raff,” which he directed, produced and starred in. The play sold out its New York City run in 1994 and was adapted into the film, “Once in The Life.”

Wilson’s early years

Wilson grew up in the Hill District, a gritty, mostly Black community adjacent to downtown Pittsburgh. He was born Frederick August Kittel, on April 27, 1945, the fourth child of seven siblings. His father was Frederick Kittel, a red-haired baked who emigrated from Eastern Europe at age 10. He mother was Daisy Wilson, a Black woman who had roots in North Carolina. She supported the family as a domestic worker. Wilson left school at age 15 when a Black teacher accused him of plagiarizing a research paper on Napoleon. Wilson’s education then came from the Black literature and other classics he discovered in Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Public Library and from the streetwise people he observed and knew from the Hill District.

Wilson doesn’t share a lot of the intimacies of his life, but a few details do surface. He’s tried to quit smoking. He stopped for a while, but after his youngest daughter was born, in 1997, he passed out cigars and was tempted to try one. Now, he’s smoking again and occasionally enjoys a cigar. He’s a big boxing fan and light heavyweight Roy Jones is a favorite. He’s twice divorced and has a grown daughter from his first marriage.

Wilson said his father had a “sporadic presence” in his own life and he wants to be a better father. He’s already picking out books he wants his youngest to read. What’s already on the shelf? Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye”; a book of paintings by Jacob Lawrence; Daniel Goldhagen’s “Hitler’s Willing Executioners”; and “Hot Seat,” a collection of reviews by drama critic Frank Rich.

“I can’t wait until she gets 17, you know, so we can talk about these things,” he said.

Wilson, of strong handshake and dashing grin, never learned to drive. He’s a lover of jazz and blues, Bessie Smith, Charlie Patton and Skip Jones are a few favorites. With the blues, Wilson believes, he’s found his song, an outlet that connects him to the history, culture and rich stories of his people.

In 1963, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, but obtained his discharge a year later.

He didn’t see his first professional play, “Sizwe Bansi is Dead,” until he was 31.

Now, 56, he’s a prolific writer who churns out his work as if he’s on a mission to make up lost time. After gaining his fame as a playwright, he focused on ending what some call segregated theater. A reference to score of playhouses in the league of regional theater, with budgets of $2 million or more, which exists to “promote and preserve European cultural values,” said Wilson.

He believes funding is imbalanced and that corporations that benefit from Black business should do more to fund Black theater. Wilson’s success has almost single-handedly cut through the cultural apartheid. Since “Fences,” the first non-musical to gross more than $11 million its debut year on Broadway, his plays have been highly sought after in regional theaters. Black dramas have cultivated Black audiences and shown regional theaters that Black theater is “good business,” he said.

Because most Americans in the theater business have a profound respect and admiration for brother Wilson, he will inspire organizations and artists to strive for the best to insure the survival of Black theater,” said Larry Leon Hamlin, director of the National Black Theater Festival and head of the North Carolina Black Repertory Co. in Winston-Salem. Hamlin.

Wilson’s loyalty to Black theater and artisans doesn’t surprise Fishburne, either.

“I believe, it’s just his character. His work speaks to certain traditions that spring from being and African American. That is what sustains him.”