Major League Baseball on Wednesday announced it will include Negro League baseball statistics with all professional baseball data, in a move that the organization announced had been in the works in a real sense since 2020, but actually decades before that.

The inclusion means the achievements of 2,300 Black players will be analyzed and potentially considered for immortality by baseball scholars, journalists, and historians.

Josh Gibson is at the top of the list for inclusion. The Pittsburgh Crawfords catcher was among the most powerful and feared hitters in all of baseball, according to peers and expert observers.

The legend was that Gibson once hit a ball out of Yankee Stadium, a feat deemed humanly impossible in the house of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, and Mickey Mantle. When the folktale was shared by a character in the 1976 movie “Bingo Long’s Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings,” a profanity-laced screaming match erupted inside a Times Square movie house among a dismissive white man and three inspired Black adolescents. Gibson’s Hall of Fame plaque at Cooperstown, New York, wrote Amy Essington in “Great Lives from History: African Americans,” confirms his career batting average at .359 and his home run total at “almost 800.”

Gibson was often teased by white sports team owners as possibly breaking the color line. However, the proposal was withdrawn multiple times. Gibson, bitter and frustrated, abused alcohol and was diagnosed with a brain tumor. His body deteriorated and Gibson died from a stroke in 1947. He was 35.

Other Negro League stars under consideration include Walter “Buck” Leonard, Oscar Charleston, David “Showboat” Thomas, Cool Papa Bell, and John Henry “Pop” Lloyd.

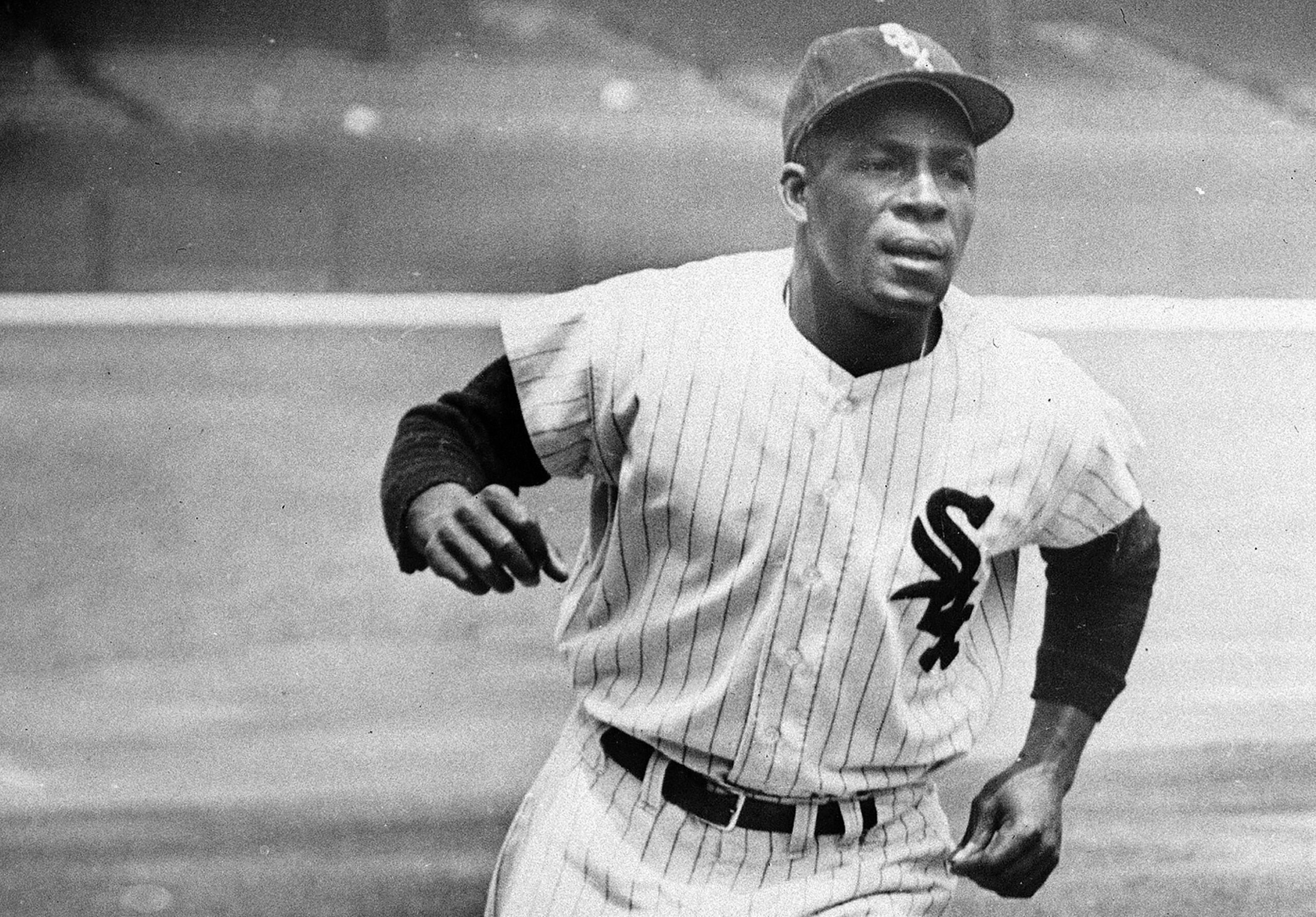

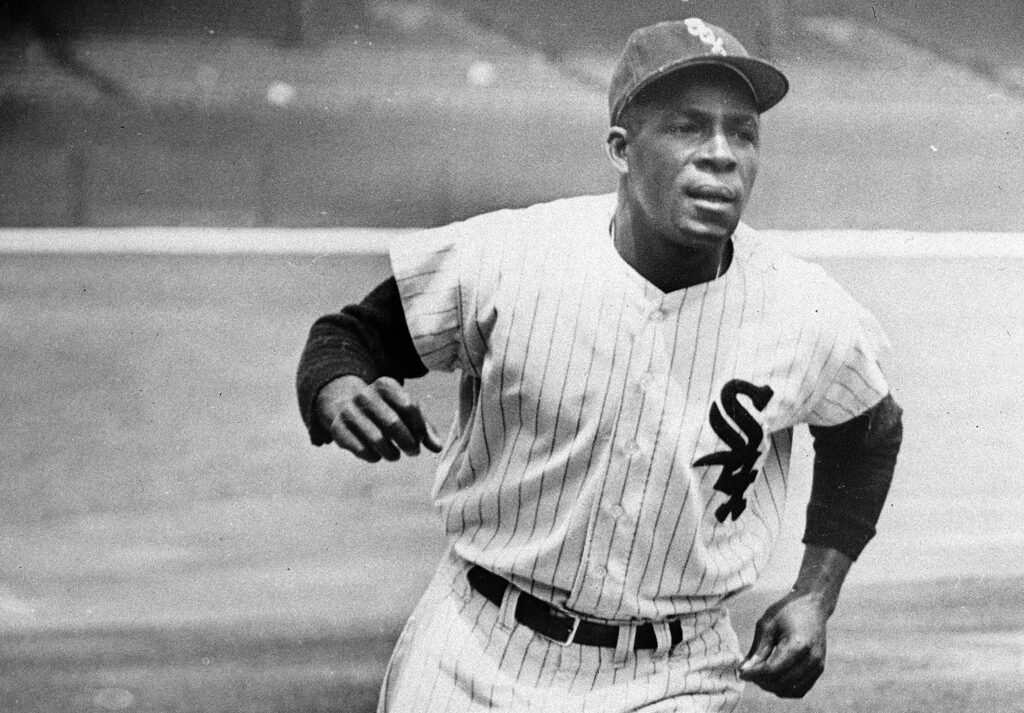

Many leading Negro League stars eventually played and became MLB Hall of Fame legends: Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Roy Campanella, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, and Leroy “Satchel” Paige.

Jackie Robinson, the four-sport UCLA varsity athlete, broke the professional baseball color line in 1946 with the minor league Montreal Royals, and then the next year with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Robinson was rated very good, but not considered the best MLB prospect by white and Black experts, however they agreed his combined athleticism, mental toughness, and character made him the person with the best chance of making it over the formidable color line.

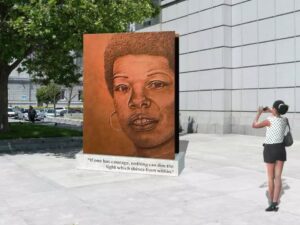

RELATED: Jackie Robinson rebuilt in bronze after Kansas statue theft

Robinson’s peer was Monte Irvin, who played for the Newark Eagles and was college-educated like Robinson. However, when Irvin was asked to join MLB, Irvin declined because he had just returned from fighting in World War II and believed he was not yet in baseball shape. Irvin did follow Robinson in MLB as a star with the crosstown rival New York [now San Francisco] Giants.

Robinson’s UCLA teammate Kenny Washington terrorized Triple-A Pacific Coast League baseball as a hitter. Washington desegregated the other professional league – the emerging NFL – with the Los Angeles Rams in the late 1940s.

When former federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis became MLB commissioner after the 1919 Chicago White Sox “Black Sox” gambling scandal, Landis enforced a gentlemen’s agreement that no Black players were allowed in professional baseball. The agreement was not in writing, which allowed nearly a quarter century of misconception. Landis was stonily silent about repeated questions of a Black ban. Owners, managers, even some white players said they wanted Black players to compete, but their hands were tied by Landis.

When Landis died in 1944, Albert “Happy” Chandler, a U.S. senator from Kentucky, promised to desegregate. “If a Black boy can make it on Okinawa or Guadalcanal,” Chandler told a group of Black press journalists, “hell, he can make it in baseball.” He kept his promise with Robinson’s 1947 introduction into MLB, then Larry Doby’s at mid-season.

Meanwhile , MLB owners rented their ballparks to Negro Leaguers at exorbitant rates [so much so, they would not let the Negro Leaguers keep the hot dog, soda pop, and peanuts concession revenues]. For example, the Washington Senators rented Griffith Park to the Grays, who made the venue their home for a few seasons, wrote Brad Snyder, author of “Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball.”

For about a century, Negro League statistics were deemed substandard compared to MLB and its Triple-, Double-, and Single-A minor leagues. An obvious flaw was some of the marginally financed Negro League teams were not able to play full seasons, so statistics were out of alignment.

However, there were other ways to measure parity.

“Based, on barnstorming games with white major league players during the off-seasons, Negro League players knew they were credible,” said Alois Ricky Clemons, a Negro League historian and MLB executive. “They beat them every time. The Negro League players knew they were on par. They were just as good and better. Once we were admitted, look at who won top awards in the next two years. We dominated the leadership then, and even today.

“The great thing about baseball is it is all about the stats. And the stats don’t lie.”

Clemmons said he was hired by MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent. “He was the first to reach out to Negro Leagues. The first to recognize them. Bud Selig followed and was first to support the Negro Leagues, with insurance [health and life] and a licensing program [jerseys, caps, other memorabilia]. That was phase II.

“Now, Commissioner Rob Manfred introduced phase III, legitimizing the statistics.”

Two Negro League players who played MLB are still alive at this writing: Hall of Famer Willie Mays [New York Mets, San Francisco Giants, New York Giants, and Birmingham Black Barons], and Bill Greason [Birmingham Black Barons, then St. Louis Cardinals for 1954 season].

The writer is author of the forthcoming, “Sam Lacy and Wendell Smith: The Dynamic Duo That Desegregated American Sports” [July, Routledge] that includes a chapter about the Negro Leagues