Deputy Steven Mills of the Lee County Sheriff’s Office was on patrol one night in 2013 when he received a call about a naked Black man walking down a rural road in Phenix City, Alabama.

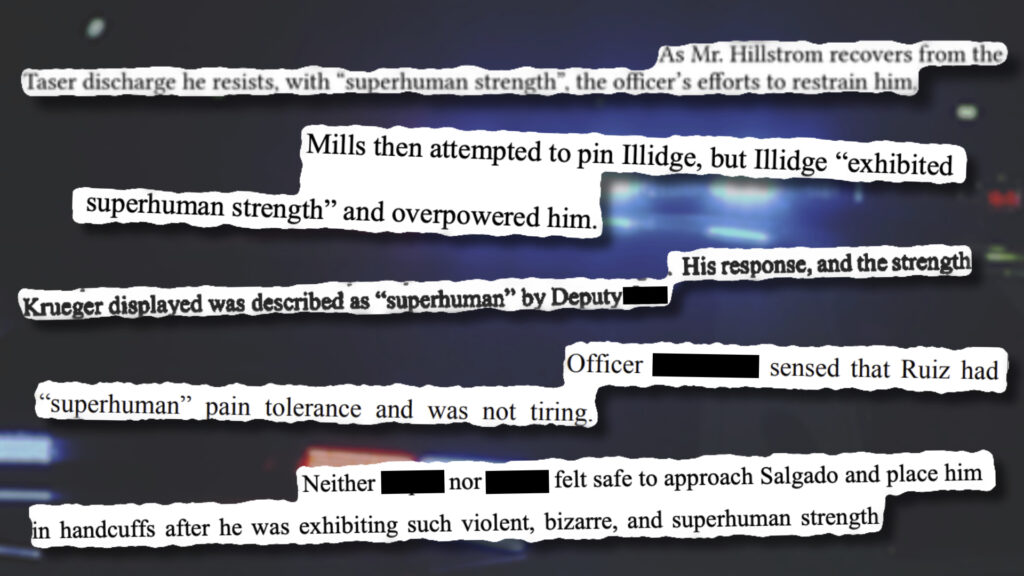

Mills said the man ignored his calls to stop, but when the officer threatened to use his Taser, 24-year-old Khari Illidge turned, walked toward him and said, “tase me, tase me.” In a sworn statement, the deputy said he shocked Illidge twice because he’d been unable to physically restrain the “muscular” man with “superhuman strength.”

Other officers who arrived at the scene used the same language in describing Illidge, who a medical examiner said was 5-foot-1-inch and 201 pounds. They bound together his hands and legs behind his back in what’s known as a hogtie restraint, and later noticed he had stopped breathing. Illidge was pronounced dead at a hospital.

Mills said in his statement that he thought Illidge was “under the influence of narcotics.” The pathologist said Illidge’s toxicology report came back negative for any “known” substances. He initially ruled there was no direct cause of death but after reviewing police reports and body-camera footage blamed the cause of death on “excited delirium syndrome as a result of an unknown substance that he ingested.”

“Excited delirium” is a hotly contested term frequently used to justify police use of force, according to law enforcement researchers and experts. The term is not widely recognized by medical associations, including the American Psychiatric Association.

One of the term’s frequently cited symptoms is “superhuman strength” — a descriptor often applied to Black people. The term creates a hurdle for legal accountability in prosecuting officers, since courts typically defer to law enforcement in determining whether force was necessary, legal experts say.

A review of dozens of police use-of-force cases, including court records, depositions and police statements, by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University, in collaboration with The Associated Press, found numerous cases in which police officers stated that a person who died while being apprehended displayed “superhuman strength.”

Seth Stoughton, a University of South Carolina law professor who served as an expert witness in the George Floyd murder trial, says the term “plays into the racist trope” of a “scary Black assailant.”

The Howard Center sought interviews with the departments and officers named in this story. None responded.

Origins of a stereotype

Although “superhuman strength” became widely publicized around the 1991 police beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles, its origins date to the post-Civil War Reconstruction era.

White Southerners spread propaganda that characterized Black men as innately savage, violent and intent on raping white women. Writers and filmmakers perpetuated the myth. The 1915 film “The Birth of a Nation” characterized Black men as rapists and beasts and used that trope to justify lynchings while glamorizing the Ku Klux Klan.

The caricature fueled widespread violence. More than 4,400 Black Americans were killed by lynch mobs between 1877 and 1950, according to data from the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit that provides legal representation to people illegally convicted, unfairly sentenced or abused in custody. Since not all lynchings were documented, it’s impossible to know their true extent.

The 1960s Civil Rights era weakened the “Black brute” caricature, as national media focused on peaceful Black protesters being attacked by police. But the “War on Drugs” and its target on communities of color helped resurrect the myth.

In a 2017 case in Arizona, Muhammad Muhaymin, a homeless man with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, was attempting to use a community center bathroom when police were called, according to records obtained by the Howard Center.

Finding an outstanding misdemeanor warrant for Muhaymin, all four officers attempted to arrest him by wrestling him to the ground. They noted in their official statements that the 43-year-old Black man had “superhuman strength.”

Muhaymin’s autopsy report said he was 5 feet, 5 inches and weighed 164 pounds. His death was ruled a homicide and, in 2021, the city of Phoenix settled a family lawsuit for $5 million.

Peer-reviewed studies on racial bias and perceived size have found that Americans demonstrate a systematic bias in their perceptions of the physical formidability of Black men. One found that white participants associated “superhuman” qualities with Black people more often than they did whites.

“Superhumanization is treating someone like a non-human,” Adam Waytz, a study author, said in an interview.

A deadly trope

Police trainers say the perception of “superhuman strength” stems from unexpected resistance not commonly seen in training scenarios.

“When you see something that’s abnormal, where a person would typically comply based on an application of force, and they don’t comply, or they seem completely oblivious to pain,” said Spencer Fomby, a national consultant with over 20 years of law enforcement experience, “I think that’s where officers start to use that terminology of superhuman strength.”

In California, Chinedu Okobi was carrying duffle bags when he was approached in 2018 by a San Mateo County Sheriff’s deputy. According to a federal lawsuit filed on Okobi’s behalf, the deputy called for backup and was joined by four others who ordered Okobi to raise his hands.

The deputy shocked the 6-foot, 300-pound Black man multiple times with a Taser, and other officers piled on top of him. One officer said Okobi had “superhuman strength” — even though he showed no signs of resistance in dashcam and cellphone video. According to the coroner’s report, Okobi died from cardiac arrest following physical exertion, restraint and “recent electro-muscular disruption.” His death was ruled a homicide.

Frank Rudy Cooper, a law professor who directs the Program on Race, Gender and Policing at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, says how officers are taught to protect themselves puts them on edge and affects how they approach certain communities.

When “superhuman strength” is allowed as a use-of-force justification in court cases, such misconceptions make their way into the wider criminal justice system. “It is an unfortunate and dangerous thing,” Cooper added.

___

Reporter Taylor Stevens contributed to this story. It was produced by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, an initiative of the Scripps Howard Fund in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard. Contact us at howardcenter@asu.edu or on X (formerly Twitter) @HowardCenterASU.