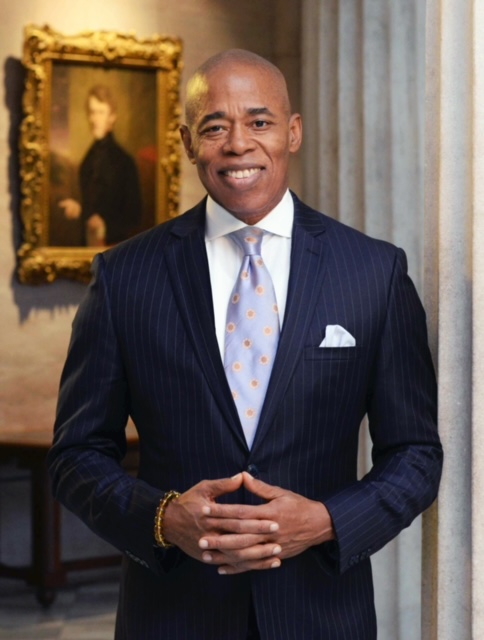

The country knows Eric Adams might become New York’s second Black mayor.

The Democrat will square off in November against anti-crime advocate Curtis Sliwa, a Republican and founder of the anti-crime Guardian Angels.

What many don’t know is that Adams is a former member of the New York City Police Department, an agency he joined because he was beaten by police in his younger days and wanted to advocate for Black citizens and police officers. On the day two planes hit the World Trade Center, Adams was a police lieutenant in Brooklyn. He was among thousands of NYPD members who responded.

No doubt, it was hazardous duty. Twenty-three members of the NYPD died in the line of duty on Sept. 11, 2001, and at least 247 have died since as a result of illnesses related to breathing dust and toxic materials at the disaster site, according to the police agency.

It was a day that changed everyone, Adams said.

“I’ve responded to many crises in my time, locally and internationally … I’ve never experienced in my life what I saw on 9-11,” said Adams, now Brooklyn borough president. “There was this eerie feeling of watching a combination of police, military, firefighters, and watching them covered in dust, the ground smoldering as far as your eyes could see, and there was this uncanny stillness in the air and it was as though we were punched in our guts.”

Adams was off that day and was in Manhattan helping with a citywide political race when he saw a crowd spilling out of a deli. He joined a group around a TV inside.

“While we were watching the announcement, another plane flew in,” Adams, 61, said in an interview. “Everyone just sort of realized it was a terror attack.”

Adams made a b-line for the subway but found the trains were stopped — a good thing, he says, because when the towers collapsed, they crushed the large train station right under them.

Adams wound up walking from Manhattan to his base in Brooklyn, a distance of about 11 miles.

“I remember getting to the precinct and going to the roof to look to see how bad the damage was,” Adams remembered. “I said to one of my police officers, ‘What happened to the towers?’ My officer said, ‘The towers collapsed.’ “

Adams was placed in charge of a platoon of officers dispatched to sensitive locations like the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the Con Edison power company. The day was fraught with intensity, particularly since the disaster caused spotty phone service. Adams’ worried about the safety of his “kid brother,” Police Sgt. Bernard Adams. The Brooklyn borough president also worried about the fate of a colleague, Officer John William Perry, who’d just retired and had to purchase a fresh police shirt so he could respond to the disaster. Perry ran into the towers and never came out, Adams said, On a positive note, Adams learned that his brother was OK. In fact he is retired and living in Virginia.

That evening, Adams went to the World Trade Center site, a place he’d patrolled many times, to witness the surreal scene.

There is no doubt that the incident was tragic — for first responders and civilians alike — but for Black Americans, there were more layers to what took place — layers that have rarely been visited previously.

According to a 2004 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, many Black Americans viewed themselves as already experiencing terrorism in their daily lives before the twin towers went down. Black people blamed the United States government for the attacks just as much as they did the terrorists, the report noted.

Another layer related to already strained relations between Black Americans and the police. The anti-Muslim stance and aggressive policing that came about as a result of the attacks set Black Americans back, according to the report.

Adams agreed.

Adams, who retired from the NYPD as a police captain in Greenwich Village, initially joined the department because of his own experience being beaten by police — wrongly, he says — in his younger days. He was considered somewhat of a rebel. In 1995, he cofounded 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care, a national advocacy group promoting police brutality reform and diversity. He also was president of the Grand Council of Guardians, a fraternal organization for Black people in law enforcement.

He brought up the Handschu agreement, a set of guidelines for New York City that forbade excessive force and unwarranted surveillance by police agencies. In 2003, after the terror attacks, a federal judge decreed that the NYPD should be allowed to modify the agreement to allow surveillance and force in the wake of the terror attacks.

“Viewing (Sept. 11) through the lens of a Black person in the department, it was rather interesting,” Adams said. “Overnight, 9-11 dismantled a lot of those safeguards and people who always wanted them dismantled celebrated. They were able to now use 9-11 as a reason to have a very heavy-handed surveillance program.”

As for lessons learned from 9-11, the former law enforcement officer said he believes we should focus the anniversary on our resilience.

“I think the day we should celebrate is 9-12 … because despite having a major punch in the gut, thousands of people lost, our symbol of strength collapsed, on 9-12 we did not miss a beat. Teachers went into schools, cab drivers drove cabs, stores opened,” Adams said. “I think the celebration should be about our resiliency because this was our Pearl Harbor moment.”