Sportswriter Chris Murray remembers well the 1971 World Series. Actually, Murray remembers legendary baseball athlete Roberto Clemente more than he does the series.

For the series was, as Murray put it, a coming out party for Clemente, one of the finest

ballplayers in the Major Leagues whose excellence was often overlooked because he

played in small-market Pittsburgh.

Clemente’s fame didn’t get much of a boost from the fact he was confident, complex — some might say cocky — and a Black Latino who didn’t speak the king’s English.

Yet whatever people did not know about Clemente the ballplayer before the ’71 series,

they knew all about him afterward.

“When I saw him, I was like, ‘Who is this guy?’ ” said Murray, who was a 10-year-old

boy rooting for his hometown Baltimore Orioles. “He didn’t care if the Orioles had four

20-game winners. He wasn’t scared of that.”

Clemente treated the baseball world to that ’71 series and then one more full season,

which he capped with his 3,000th hit. But on New Year’s Eve of 1972, he died doing

what most people inside and outside of baseball didn’t know he did — giving back to the

sick and the needy. Clemente, three crew members and another passenger died en route to Nicaragua, where a magnitude-6.3 earthquake struck on Dec. 23rd near Managua, the capital, killing between 4,000 and 11,000 people.

The Douglas DC-7 carrying Clemente and the three others crashed shortly after takeoff from San Juan, Puerto Rico.

The bodies were never recovered.

In its New Year’s Day edition, The New York Times wrote:

SAN JUAN, P.R. Jan 1 — Roberto Clemente, star outfielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates,

died late last night in the crash of a cargo plane carrying relief supplies to the victims of

the earthquake in Nicaragua.

Government officials in Clemente’s native Puerto Rico declared three days of mourning for

the athlete, the most celebrated figure in the island’s history.

Despite concerns about the aging aircraft and the heavy load it carried — concerns that Clemente’s wife, Vera, raised — Clemente insisted he must go. He wanted to make certain, he told Vera, that the humanitarian aid didn’t get into the hands of profiteers.

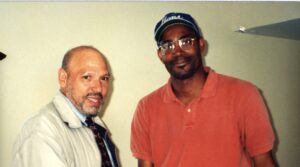

He wouldn’t allow it, said Rob Parker, a multimedia personality, former baseball writer

and founder of the website MLBbro.com.

“I think Clemente is who we all wish we would be or could be — which is a star in his

own right but never forgetting other people,” Parker said. “That’s a trait most people

don’t have or most people can’t obtain.”

In death, Clemente became a mythic figure, Parker said. His heroism and humanity will

endure as long as people — Hispanics, Blacks or whites — can utter Clemente’s name.

It certainly will be in Pittsburgh and around Major League cities.

During road trips as a Pirate, he often visited sick children in hospitals. He organized

baseball clinics where he taught boys and girls how much fun the game was. In the

weeks before his death, he held a clinic for more than 300 youths in his native Puerto

Rico.

Clemente was an ambassador for the game, just as were athletes like Buck O’Neil, Ernie Banks, Bob Feller and Minnie Minoso.

Five decades later, people who follow baseball still remember how he died; they should

remember how the man lived too, Murray said.

Clemente the man

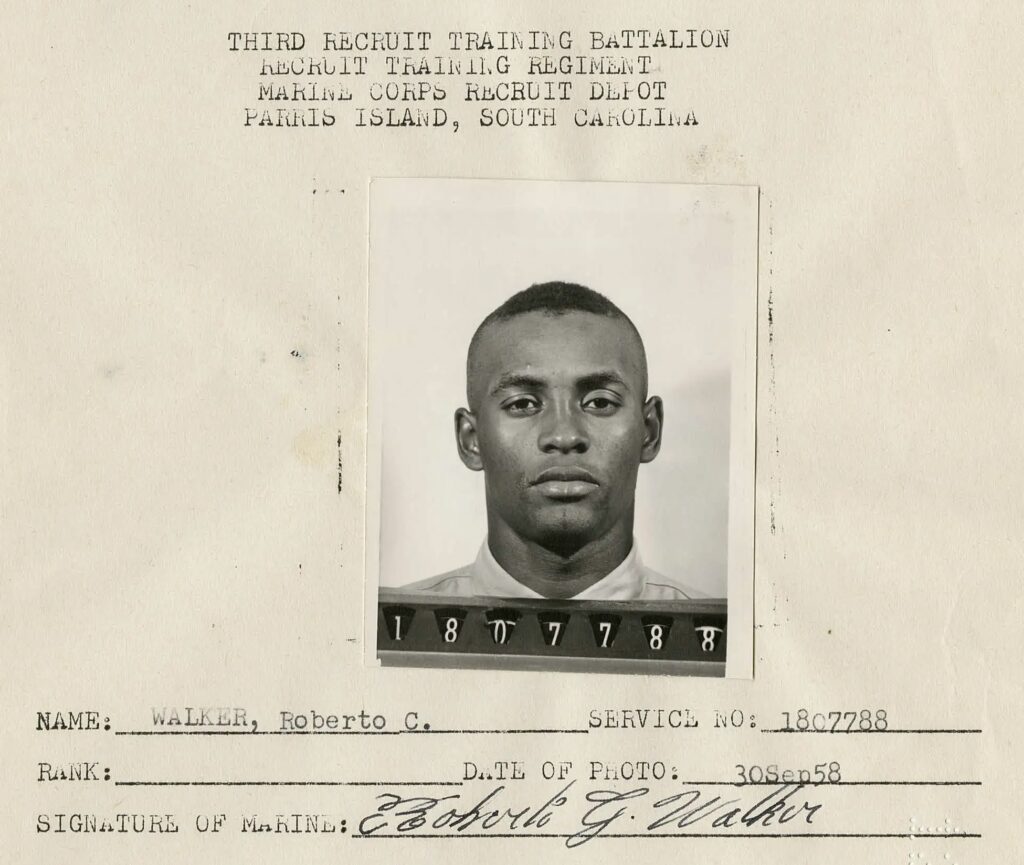

Born in Carolina, Puerto Rico, Roberto Clemente was the youngest of seven children.

He grew up in the 1930s and 1940s, and he worked with his father loading sugarcane

onto trucks. Thanks to his mother Luisa, he picked up a passion for baseball.

Before reaching his late teens, Clemente was a player that Major League teams were

scouting.

The scouts for the Brooklyn Dodgers liked what they saw.

On February 19, 1954, they signed the 18-year-old Clemente, a dark-skinned Puerto

Rican, to a $5,000 salary with a $10,000 bonus, and added him to its stable of talent.

The Dodgers sent him to Montreal, which is where Jackie Robinson began his career in

integrated baseball.

But the Dodgers used Clemente sparingly, as if trying to hide his talent from another

Major League ball club. They failed.

In the November 1954 Rule 5 rookie draft, the Pirates snatched Clemente from the

Dodgers farm system for $4,000. They wasted no time getting him into the starting

lineup.

On April 17, 1955, he made his Major League debut.

In his rookie season, he faced bigotry and isolation from white teammates. The fact

that Clemente struggled with the English language made his plight around Pittsburgh

even more discomforting.

“I didn’t even know about (racism) when I got (to the United States),” he was quoted as

saying in 1972.

Like Robinson, Larry Doby and Monte Irvin, Clemente worked hard to change people’s

minds about hatred and prejudices, which he said hung over darker-skinned Latinos just

as it did “Negroes.”

“Because they speak Spanish among themselves, they are set off as a minority within a

minority,” Clemente once said of darker-skinned Latinos. “They bear the brunt of the

sport’s remaining racial prejudices.”

Journalist/activist Murray agreed.

“Clemente was an activist.,” said Murray, who hosts a weekly sports podcast. “He

insisted on being called ‘Roberto,’ not ‘Bobby’ as [Pirates] announcer Bob Prince called

him. He wanted people to respect him because of his Black Latino heritage.”

As he became more fluent in English, Clemente spoke more candidly about the ridicule,

his race and racism, echoing the views of civil rights figures like King, Robinson and

Puerto Rican activist Luis Muñoz Marín.

Clemente never let racism affect his play on the field.

Instead, he treated Pirates fans — and everybody else who followed baseball — to

some of the finest performances the game had every witnessed.

No man ever played a better right field than Clemente, which his 12 consecutive Gold

Gloves prove. Few hit a baseball better than he did. His all-round talent was visible to

everybody.

Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown thought so.

“The sad part is that there are not enough TV pictures of him,” Brown said shortly after

Clemente’s death. “He made so many great plays that people can only talk about. You

could never capture the magnificence of the man.”

Reminiscing once, Clemente wondered why baseball fans viewed Babe Ruth, whom

most referred to as “the best there was,” the way they did. A player would have to be

extraordinary to earn comparisons to Ruth, Clemente mused.

“But Babe Ruth was an American player,” he said. “What we needed was a Puerto

Rican player they could say that about, someone to look up to and try to equal.”

They got that someone in Clemente.

His legacy

“I want to be remembered as a ballplayer who gave all he had to give,” Clemente once

said.

And he will be.

But that giving was as much off the field as on it.

He was Puerto Rican, but Clemente was also Black man who played baseball in

Pittsburgh, an uneasy combination in a country were racism persisted.

He was a reminder of what some historians referred to as a “hemispheric diaspora,” a

world that included Canada, Mexico, Central America, South America and the

Caribbean. Clemente’s voice and public persona made people aware of the cultural

diversity woven into Blackness.

Quoted in an article in The Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, his son Luis admitted that his

father’s legacy might stand tallest in the sport itself.

“My dad did stuff that still today no other player has done,” said Luis, who was 6 when

his father died. “But his humanitarian side is what really perpetuated him in such a way

that people who are not even sports or baseball fans still admire him for who he was as

a human being.”

Justice B. Hill grew up and still lives on Pittsburgh’s East Side. He practiced journalism for

more than 25 years before settling into teaching at Ohio University. He quit May 15,

2019, to write and globetrot. He’s doing both.